Top: West Haven set up displays (left) at various venues to educate residents about the pilot and distribute bags. Sorting line to separate orange and green bags (right) collected at curbside in West Haven. Photos courtesy of WasteZero

Nora Goldstein

In late October, the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP) announced grant awards to 15 municipalities and three regional groups that total close to $5 million. The grants, administered by DEEP’s Sustainable Materials Management (SMM) program, are for development of residential food waste collection and unit-based pricing pilot programs. These types of waste diversion initiatives were recommended by the Connecticut Coalition for Sustainable Materials Management (CCSMM), notes a DEEP press release, a coalition of over 100 municipalities across the state working on ways to reduce waste and increase reuse and recycling.

Connecticut relies heavily on aging disposal infrastructure in the state through which the majority of solid waste is incinerated to generate energy. The pilot programs are designed to reduce the amount of trash in these communities and reduce reliance on this infrastructure or out of-state-landfills. The July 2022 closure of the Hartford (CT) Resource Recovery Facility, owned by the Materials Innovation and Recycling Authority (MIRA), left 36 communities without a disposal site. This has strained operations at the three incinerators remaining in Connecticut, which are all over 30 years-old.

“The wait time to unload at the Bridgeport incinerator that we use is often up to 6 hours,” says Douglas Colter at the Department of Planning and Development in the City of West Haven, one of the municipalities receiving a SMM grant for a food waste collection program. “That leads to inefficiencies in collection, lost man hours, idling pollution and wasteful use of expensive diesel fuel. It also puts the current $67/ton tip fee at risk of almost doubling to $120/ton in the near term, to upwards of $200/ton [per DEEP forecasts] soon thereafter. The City of West Haven will tack on $1.5 million to our waste management budget due to increasing disposal costs. This is hard in a municipality that often struggles to afford fire and police protection or hiring a new school teacher.”

According to Connecticut’s most recent waste characterization study, 41% of what residents throw away is organic material such as food waste (22% of residential trash) and yard trimmings. Due to the Hartford incinerator’s closure, DEEP anticipates up to 30% of the state’s solid waste will be shipped to out-of-state landfills. Currently exported trash goes to landfills in Pennsylvania and Ohio, adds Colter. “Once out-of-state commercial landfills see demand, likely their tip fees will rise as well. The pressure is on local governments to come up with solutions at a level and scale that is beyond our financial resources. What DEEP is doing is recognizing the fact that solutions, such as the pilot projects, need to be supported at the state level.”

Collection Pilots

One of the models being implemented for the residential food waste pilots is cocollection in the same cart as trash. The City of Meriden (CT) received a DEEP grant earlier in 2022 to run a 4-month, 1,000-household test to prove the feasibility of cocollection of food and household waste and the ease-of use for residents. Meriden households used two special bags during their pilot— a green 8-gallon bag for food waste, and an orange 15-gallon bag for trash. Both bags were collected weekly in the same bin, then separated by type. The food waste bags were transported to Quantum Biopower in Southington, where they were preprocessed in a Scott Equipment Turbo Separator; the resulting slurry was pumped into the digester tanks. The pilot diverted over 13 tons of food waste.

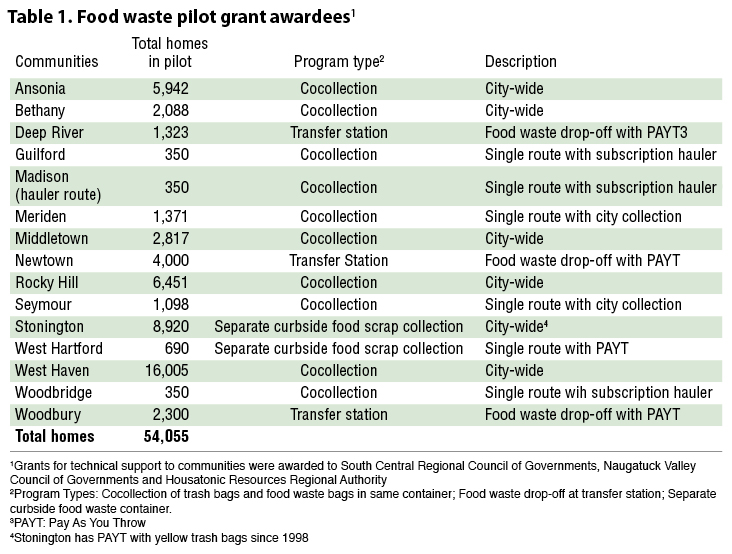

Ten of the 15 communities receiving grants are utilizing the cocollection model (Table 1). Two are having households separate food waste into a separate container that is picked up curbside and taken to a composting facility. The remaining three are utilizing food waste drop-off sites located at transfer stations.

The City of West Haven, which received a $1.3 million grant, opted for cocollection and launched its program on November 1. There are 16,500 households eligible to participate in the voluntary program that is servicing single-family and up to 3-unit dwellings. Owner-occupied condominiums will be added to the program if it is permanently adopted. “About 70% of the households are single-family,” notes Colter. “About 40% by weight and 20% by volume of the trash the city currently tips at the Bridgeport incinerator is organic waste. Our pilot is taking the food waste bags to Quantum Biopower, where the tip fee is actually trending down in price instead of increasing like the incinerator tip fee. This is definitely an incentive to both succeed with the pilot and adopt this on a permanent basis.”

All participating households received a 9-month supply of 8-gallon polyethylene (PE) food waste bags and 13-gallon PE trash bags (equivalent to 2 trash bags and 1 food waste bag/week). Additional trash bags can be purchased for $0.35 each at retail stores in West Haven. “We did 9 days of person-to-person interactions at supermarkets and other public locations, educating residents about the program and distributing the bags,” says Kristen Brown of WasteZero, the consulting firm hired by DEEP to help the 15 communities implement their pilot programs. “Between those activities and then door-to-door distribution of bags, we spoke with about 10,000 people. West Haven will make some countertop containers available at city hall later in December, but households are encouraged to reuse lidded containers they may already have in their kitchens and line it with the green food waste bag.”

All food waste is accepted, including vegetative, meat, dairy and fish, and other items such as coffee grounds and tea bags, cut flowers, and food-soiled napkins and paper towels. Collected bags are taken to a transfer station equipped with a conveyor belt and sorting stations. The green and orange bags are separated by sorters and dropped into dumpsters used to transport trash to the incinerator and food waste to the digester. “The bags get weighed, and there are six sorters on the line,” explains Brown.

Evaluating Unit-Based Pricing

The pilot is scheduled to run through June 2023, although the city may extend it depending on funds left in the grant. “The orchestration of managing the pilot and the messaging to residents were the biggest budget items to launch the pilot,” explains Colter. “Those costs were shared by our city and the state grant. We anticipate being able to provide enough data on the results of the pilot to City Council by May 2023. Then, a decision to make the program permanent is up to the taxpayers and our local government. One question we expect to be debating is whether costs for the cocollection program will be covered by our waste management budget, which is funded by taxes, or if we shift to pay as you throw (PAYT) unit-based pricing, and thus shift some of the costs to the residents and not cover these costs by taxation. It is a decision that residents will have to make. Another factor, which we should have a clearer picture of towards the end of the pilot, is the new tipping fee at the incinerator and how that impacts our budget.”

Residents place food waste bags in the same container as the orange trash bags. Photo courtesy of WasteZero.

Utilizing a bag-based program for trash and food waste may help facilitate a shift to PAYT unit-based pricing in West Haven, and in other Connecticut communities initiating food waste recycling. Evaluating options is part of the DEEP food waste pilot grants. “Standardizing the bags, and pricing them so that trash is more expensive than food waste, incentivizes recycling for both organics and recyclables,” notes Brown, who specializes in unit-based pricing strategies. “The increases in cost of disposal, e.g., incineration or out-of-state landfills, are built into the cost of the trash bag, and help offset the cost of the organics and recycling streams. This bag-based cocollection model is widely used in countries like Norway, Sweden, France and Belgium. Some facilities employ optical sorting equipment versus manual labor to separate bags of trash and organics, which dramatically reduces the cost of cocollection — savings that can be passed on to the households serviced by the program.”

Another consideration when evaluating options is the carbon footprint of each food waste recycling solution, including anaerobic digestion, incineration and composting. For example, notes Colter, both Quantum Biopower and the Bridgeport incinerator generate electricity, which has associated carbon emissions. “Composting has its own carbon footprint, but it is less than incineration and large-scale biodigestion,” he says. “In a perfect world, households would put the food waste in their own backyard bin. But West Haven, like many communities, is very much a community which accepts that government provides waste management.”

The City of West Haven has been conducting a food waste composting pilot at its leaf and yard trimmings composting facility, funded in part by a grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service Urban Farming program and the Connecticut Recyclers Coalition. The city utilized a modular extended aerated static pile (EASP) unit supplied as a demonstration project by Atlas Organics. “The pilot was very successful,” says Colter. “After the Atlas demonstration concluded, we opted to build our own EASPs and are now logging data for the project. We are very confident we can manage residential food waste right here in West Haven if the state develops a permit system for such an operation. The barrier to managing our own food waste is plastic contamination. The scale of a biodigester is large enough to afford the expensive waste separation equipment and labor to get plastic contamination out of the food waste. This would be cost prohibitive at our composting scale. We would need 100% consumer cooperation to make this work in a composting model.”