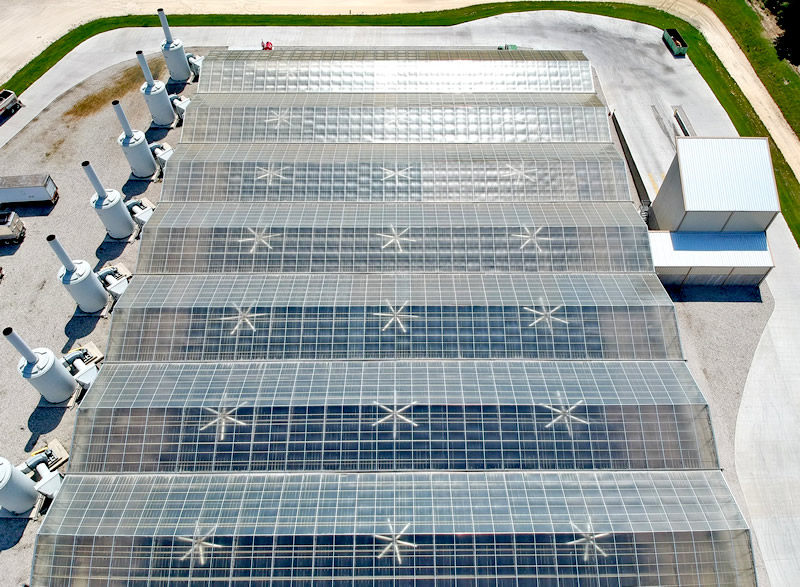

Top: The Pasco County (FL) biosolids recycling facility includes two solar greenhouses and a separate building for oven pasteurization of the dried solids. Photos courtesy of Merrell Bros.

Nora Goldstein

Ted and Terry Merrell were each given one female pig when they were young teenagers by their father to raise on their family’s farm in Kokomo, Indiana. “One pig turned into two, then 20, and by the time they graduated from high school, they had rented hog barns and feeder pig lots in four counties and were driving almost 100 miles every day to do chores,” according to the company history on the Merrell Bros.’ website. Dealing with hog manure was a continual challenge, especially when confinement of hogs in barns began. The hog manure dropped into pits beneath the barn, which needed to be pumped out and the manure land applied. Given the number of farms and the volume of manure, the Merrell brothers invested in an Ag Chem high flotation Terra-Gator spreader to facilitate servicing the hog farms.

Their entrée into biosolids was in 1985, when they helped a local contractor pump out a lagoon at a wastewater treatment plant. The next year, the Merrells decided to bid on a biosolids management contract for the City of West Lafayette, Indiana and won the bid. “We’ve been the city’s service provider ever since,” notes Blake Merrell, Ted’s son. The brothers eventually sold their shares of the hog farm business to their other partner [their brother-in-law], and moved fully into servicing the wastewater treatment sector.

“Our specialty was lagoon cleanouts, using mobile dewatering belt filter presses, and then hauling the biosolids to farms to be land applied,” he adds. “We were working on projects in multiple states, including Nevada and Texas. At this point, we have serviced wastewater treatment plants in 35 states, but during an average week, we are working in 9 to 10 states at any one time.”

One operator can run multiple belt presses from the cab of the truck when cleaning out lagoons at wastewater treatment plants.

Merrell Bros. fine-tuned the lagoon cleanout and dewatering process to the point that one operator can run four belt filter presses at the same time. “The operator can sit in the cab of the truck and monitor the process using 16 different cameras that we install at various points, starting with the lagoon and then to the belt presses,” says Merrell. “The polymer chemical used for dewatering is auto-dosed onto the press. This efficiency enables us to be very competitive on lagoon cleanout bids, where we can have three operators and 12 belt filter presses running at the same time.”

Biosolids Recycling

While application of biosolids on agricultural soils has been a primary outlet for the dewatered material, in some states land development is making that increasingly challenging. “This is especially true in Florida, where I’m located,” notes Merrell. “Several biosolids composting facilities are available, but in some cases, we found ourselves having to haul biosolids from Florida to Georgia to landfill.”

A lagoon cleanout and dewatering contract with Pasco County, Florida is what brought Merrell to the state around 2009. In the early 2010s, Pasco County issued a Request for Proposals (RFP) for a public-private partnership to manage about 50,000 wet tons/year of biosolids that were being landfilled. The contract was awarded to a company that was going to make biodiesel using the biosolids as a feedstock. Merrell Bros. came in second. As it turned out, the biodiesel project did not come to fruition, so Pasco County awarded the project to Merrell Bros. in 2015. The public private partnership included a design, build, and operate (DBO) contract where Merrell Bros. was hired to design a turnkey facility, fully build it under its construction division (Merrell Bros. Construction LLC), and then operate the facility under a 25-year agreement with renewal options. Pasco owns the building structures and facility location, and the company operates the facility for an annual service fee.

“Our proposal was to make a fertilizer product out of a dried biosolids,” he explains. “We’ve been doing that in Indiana to treat a number of regional wastewater plant biosolids at one location. The process reduces the water weight and therefore the volume of biosolids that need to be land applied. We create windrows, and turn with a Brown Bear unit until the material is dried to about 45% solids. Once homogenized, the solids are tested to determine the combined source nutrients in order to calculate the application rate and nutrient content of the material. The Class B product is applied on thousands of acres of corn that Merrell Bros. grows for its grain business.”

Dewatered biosolids are laid out on the greenhouse floor and tilled with a tractor about once a day to facilitate drying.

That outdoor process was not suitable for Florida, primarily because of the need to manage odors. In addition, the company wanted to produce a Class A biosolids that could be sold to multiple end markets. Under the U.S. EPA’s Part 503 regulation, Class A requires the material to go through a PFRP (Process to Further Reduce Pathogens) process. Merrell Bros. had proposed to do the first stage of the drying inside two solar-heated greenhouses, followed by oven pasteurization, also known as belt drying, where PFRP would be met (video below shows the entire process). It took 1.5 years to work out the contract and design details, and construction got underway in late 2016. Merrell Bros. markets the end product under the brand FloridaGreen.

The plant began operating in Spring 2018. There are two fully enclosed greenhouses, each 65,000 square feet. Biosolids are received from four wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) in Pasco County, as well from WWTPs outside of the county. Incoming biosolids, dewatered to about 15% to 18% solids, are laid out on the concrete floors with mini front-end loaders. A tractor is used to till the material about once per day. This brings the wet material on the bottom layer up to the surface to dry.

Each greenhouse has 21 ceiling fans that continually move about 3.5 million cubic feet of air. Building air passes through carbon filters (stacks) to scrub out the ammonia before being discharged.

Each greenhouse has 21 ceiling fans that continually move about 3.5 million cubic feet of air. Fans mounted on the side of the greenhouses pull 200,000 cubic feet/minute (cfm) through the structure, providing 12 air changes/hour (every 5 minutes). The air passes through carbon filters (stacks) to scrub out the ammonia before being discharged. After 10 days to two weeks, the solids content is between 50% to 60%. At this point, the remaining water is more difficult to evaporate because the outside of the solids has formed a crust. The reduction in volume of biosolids after solar drying is about 33%.

Conveyor belts move the solids through the oven pasteurization process.

Next, the solids are conveyed to a 3-story building (about 26-feet tall) that houses the pasteurizer oven, motor control room, parts storage, and some office spaces. The solids drop into a “day hopper” and then go onto a conveyor belt at a depth of 2- to 3-inches. Hot air is forced through the conveyor belt at a rate of 30,000 cfm, which assures that all the material on the belt gets heated from ambient temperature to about 70°C, or 158°F. The speed of the belt can be adjusted, depending on the amount of time required to get all the solids up to 70°C.

Next, the heated solids fall onto a conveyor belt in the lower chamber of the oven pasteurization unit. PFRP is achieved by solids remaining on the belt at a temperature of 70°C for 30 minutes. “The belt speed assures that the material stays in the lower chamber for the required amount of time to make a Class A biosolids product,” explains Merrell. “After that 30-minute period, the treated solids can be conveyed into a trailer to be taken to market or be loaded into a storage hopper. The final FloridaGreen product is 86% to 90% solids. It is porous and light and looks like gravel.”

Typical rotary drum dryers heat the biosolids to much higher temperatures, which drives off nitrogen, he adds. “Our process does not offgas the N. It has a 6-8-1 N-P-K [nitrogen:phosphorus:potassium] value. FloridaGreen is sold to composting facilities for soil blending, sod farms, fertilizer manufacturers, sugar cane growers, orchards and other agricultural producers. We are actually sold out until 2024.”

The next step is to construct a bagging facility. The cement has been poured. FloridaGreen will pelletize the product and package it in 30-lb bags.

Materials Transport

When Merrell Bros. started providing biosolids dewatering and hauling in Florida in 2010, it saw an opportunity to expand its materials transport services, especially for the composting facilities where it was bringing the biosolids. “We figured out pretty quickly that the facilities needed reliable supplies of wood chips for composting,” says Merrell. “We owned KEITH Manufacturing WALKING FLOOR® trailers for hauling biosolids, and decided to bid on some more routine storm debris management contracts to move out the wood waste, either chipped or unchipped. We also could transport screened compost to end markets.”

Merrell Bros. has a fleet of KEITH Walking Floor® trailers that it uses to haul a wide range of materials, including storm debris (top) and biosolids (above).

The company now has over 50 trailers with KEITH floors. Most have the KEITH® 2299 Impact flooring that is 48-feet long about 8.5-feet wide, and are equipped with the KEITH Running Floor® II DX drive with 3.5-inch cylinders for unloading larger payloads. “We’ve expanded into hauling recyclables such as cardboard and plastic, as well as MSW,” he adds. “The Walking Floors, especially the 48-foot long floors, are a perfect size for trash, compost and green waste. It’s like having a drill that you can use to mix a can of paint with a mixing paddle as well as drill a hole through steel. It’s the right tool for both jobs. The floors are easy to clean out when we switch from one type of material to another. And all have electric tarps, which is a big deal for retaining drivers. The operator just has to hit levers and buttons. We are hauling over 2 million tons/year of materials in the trailers.”