While Canada has only two commercial-scale projects producing renewable natural gas for vehicle fuel, and several others in development, its potential is significant.

Peter Gorrie

BioCycle June 2014

Compressed natural gas produced by EBI Énergie from landfill biogas helps fuel the waste collection trucks operated by a sister company. The RNG is supplemented with fossil natural gas.

Total biogas production from anaerobic digesters, waste-water treatment plants and landfills is still a tiny fraction of Canada’s energy mix, and most is burned to generate electricity. A few operators, though, are shifting toward upgrading the raw gas into a vehicle fuel, also known as biomethane or renewable natural gas (RNG), that’s chemically equivalent to conventional, fossil natural gas. “Vehicle fuel is the logical path for RNG in Canada,” says Stephanie Thorson, who works with the Biogas Association, a major advocacy group, and one of the country’s leading proponents for what’s considered the greenest transportation energy source.

The industry is small: Canada now has only two commercial-scale projects producing RNG for vehicle fuel; a handful more are at various stages of development in three of the 13 provinces and territories. (See project descriptions later in this article.) Nevertheless, RNG “has huge potential in transportation,” says Alicia Milner, president of the Canadian Natural Gas Vehicle Alliance, which includes the country’s main natural gas producers and distributors. “There’s no other zero emission alternative available for heavy on-road trucks and other commercial vehicles.”

Since most RNG will be used to supplement conventional natural gas, the two alternative fuels must develop together. For now, the market is tiny: According to the Alliance, only 12,000 of the country’s roughly 22 million vehicles run on natural gas, and there are just 60 publicly accessible sites for fueling them.

Still, Milner points out, while medium and heavy vehicles account for less than five percent of all on-road vehicles, they use roughly one-third of all energy in the transportation sector. Within this group, fleet vehicles that return to the yard at night or that operate in regional corridors may be well suited to natural gas use with targeted private or highway corridor infrastructure investments.

This has led to a “niche” approach, very different from what was done in the past, when the natural gas vehicle industry tried to mimic the model for gasoline and diesel — attempting to cater to all types and uses of vehicles. Matching the existing network of stations for those fuels would require a massive expansion of fueling facilities, which cost up to $2 million each, and require a dramatically increased willingness among fleet operators and other fuel consumers to acquire vehicles powered by natural gas.

RNG Hurdles

From production to consumption, RNG boasts the smallest carbon footprint and the lowest greenhouse gas and toxic emissions of any vehicle fuel. It’s also cheaper than the current dominant fuels, gasoline and diesel. But it’s significantly more expensive than conventional natural gas, which many consider the heir apparent to the traditional fuels, and it requires expensive equipment for upgrading from biogas.

Farm-based anaerobic digesters, fed mainly by manure and food processing wastes, are ideal sources of biogas for conversion to RNG. But Canadian livestock farms are typically much smaller than their American counterparts — nothing in Canada compares, for example, with the 11,500-head Fair Oaks Farms dairy operation in Indiana that is fueling its milk delivery trucks with RNG (see “Building A Biogas Highway in the U.S.,” March/April 2014). This makes it tougher to justify the cost of building digestion facilities, let alone the equipment to upgrade the biogas to RNG.

And RNG gets less government support than other types of renewable energy. The federal Canadian government has contributed small amounts to projects in Surrey, British Columbia and Hamilton, Ontario, promises partial support for biogas facilities in Montreal and recently pledged $15 million over three years, matched by the distribution industry’s Canadian Gas Association, for research into “the development and demonstration of new downstream natural gas technology, including technology related to the development of renewable natural gas.”

Canada, unlike the United States, also has national technical guidelines for allowing RNG into the pipeline grid. “That’s helpful, “ Milner says. “It sets a clear standard.”

But the federal government hasn’t imposed a national mandate for RNG as it has for ethanol, which must comprise at least five percent of gasoline, and biodiesel, which must constitute at least two percent of all diesel fuel. Five provinces have similar minimum content rules for ethanol and biodiesel but not for RNG. Canada also lacks incentives such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Renewable Fuel Standard and California’s Low-Carbon Fuel Standard Program to kick-start the industry. “We’re trying to create the same regulatory regime for RNG as for ethanol or biodiesel,” says Thorson. “We’re also trying to find a way so that vehicles will have an RNG requirement.”

In Ontario, the most populous province, a Feed-in Tariff (FIT) program pays a premium price for electricity generated from renewable sources. That program offers the security of 20-year contracts with built in cost-of-living increases, and remains the most attractive option for biogas, Thorson notes. For now, “folks look at RNG mainly if they can’t get a FIT contract, or can’t get connected to the electricity grid,” she explains. “RNG comes up as the next best thing. A renewable natural gas equivalent to the FIT would be the preferred model. We could bring the industry up to scale.”

But the Ontario Energy Board, which regulates the industry, slammed the door on a FIT-like program when it rejected applications from the province’s two major distributors, Union Gas Limited and Enbridge Inc., for customers to pay a premium price for RNG injected into the pipeline grid. Quebec’s regulator followed with a similar decision.

However, British Columbia (BC), the third province with RNG production, allows this green premium as a voluntary option. As a result of that and other favorable policies, the province’s major distributor, FortisBC, has opened three RNG facilities and invites residential customers to pay about $5/month extra to have RNG injected into the pipeline grid on their behalf. Demand exceeds supply, and the company — a subsidiary of Fortis Inc., Canada’s largest investor-owned distribution utility — has received approval from the BC Utilities Commission for four more facilities. While the policy mainly promotes RNG for domestic heating and cooking, it is bolstering a proposed vehicle fuel project. It also shows the power of supportive regulations.

Municipalities Can Drive Demand

In the absence of such regulations elsewhere, “the industry is trying to find leaders in industry and government to drive the market,” Thorson says. At the moment, the Biogas Association is focusing on municipal governments to lead the way. To that end, it recently created an RNG working group with Quality Urban Energy Systems of Tomorrow, or QUEST, a national network of government and industry representatives — including some from major oil companies — that aims to make Canada a leader in “smart energy communities.”

“We see opportunities with municipalities to build demand for RNG,” particularly since most have sustainability goals, face waste diversion mandates and could benefit from reducing costs for waste management and vehicle fuelling, says Samira Drapeau, coordinator of QUEST’s Ontario caucus.

Municipal governments operate or administer vehicle fleets, such as garbage trucks and transit buses, ideally suited for conversion to natural gas, and RNG, because they follow set routes and return to the same base at the end of each day, Thorson adds. Their landfills and wastewater treatment plants can produce large amounts of biogas and residential organics collections provide a reliable feedstock for digesters while eliminating a costly disposal problem. “With municipalities onside we hope it will be easier to approach corporations with sustainability targets,” Thorson says. “That will be Phase Two.”

But this effort is still at the exploratory stage: The working group held its first meeting just last month.

Operating RNG Projects

Hamilton, Ontario

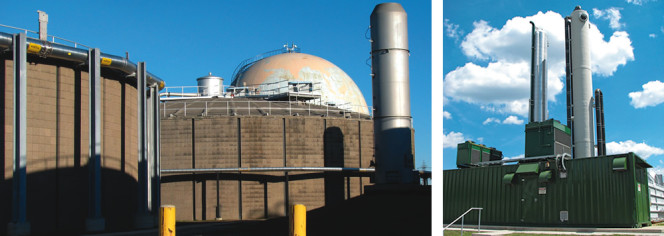

The City of Hamilton, located 45 minutes southwest of Toronto, produces biogas at its Woodward Avenue wastewater treatment plant. Some is burned to generate heat and electricity, but three years ago the facility added equipment to upgrade a portion into RNG. The city’s original plan was to dispense RNG directly into city vehicles that make regular stops at the site. However, it switched to a complex “wheeling” arrangement with the local distributor, Union Gas Limited, a subsidiary of Spectra Energy of Houston, Texas.

The City of Hamilton, Ontario produces biogas at its Woodward Avenue wastewater treatment plant (left). The biogas is upgraded to RNG standards in a water scrubber system (right) supplied by Greenlane Biogas. Photos by Peter Bromley, City of Hamilton

The City of Hamilton, Ontario produces biogas at its Woodward Avenue wastewater treatment plant (left). The biogas is upgraded to RNG standards in a water scrubber system (right) supplied by Greenlane Biogas. Photos by

Peter Bromley, City of Hamilton[/caption]Under this deal, the RNG is injected into Union Gas’ pipeline grid, where it displaces a small part of the conventional flow. Union Gas doesn’t pay for this supply. Instead, it charges the city a small fee to transport the gas. The city then buys the remainder of its required supply for its vehicle fleet by conventional means, with a deduction for the amount of RNG it has put into the pipeline. The biogas is upgraded to RNG standards in a water-scrubber system developed by Greenlane Biogas, a division of the New Zealand-based Flotech Group. The project was partially funded by economic stimulus grants from the federal and Ontario governments.

Widespread conservation measures and a business decline have combined to cut the flow of effluent to the treatment plant, leading to reduced biogas production, notes Dan McKinnon, director of water and wastewater operations. The cogeneration plant is operating at full capacity, leaving enough biogas to keep the RNG upgrader running at about 24 percent of its capacity. “We still have a decent amount of gas but not as high as we thought it would be,” McKinnon says. Although flows into the treatment plant are increasing again, expansion plans have been pushed back to 2023.

Still, Hamilton is considering buying additional natural gas buses, and McKinnon’s department is looking into centralizing its vehicle fleet to make better use of RNG. As well, he says, the potential for acquiring new feedstocks is being investigated but there’s “nothing firm on the hopper currently.”

Saint-Thomas, Quebec

In Quebec, compressed RNG produced by EBI Énergie, the renewable energy arm of a family of companies that includes solid waste collection and disposal, helps to fuel 80 of the waste management company’s trucks. The RNG, produced at a landfill site in Saint-Thomas, a town about 40 miles northeast of Montreal, is injected into the pipeline grid, where it displaces a small amount — about 32,000 cubic meters/day — of conventional natural gas. “We are in the process to completely convert our 120-truck fleet to CNG,” says director of engineering Luc Turcotte. “Our objective is to replace every diesel truck in our company no later then 2015.”

That conversion will, in turn, add to the number using the RNG put into the pipeline. “Most of our trucks are dedicated to waste hauling activities,” Turcotte adds. “So, it is great to see the whole cycle: We are collecting wastes, we are producing landfill gas from these wastes, we are refining the gas into renewable natural gas and, finally, we are fueling our trucks with this gas.”

In addition, Quebec’s main natural gas distributor, Gaz Métro, plans to add liquefied RNG (equivalent to liquefied natural gas) to its “Blue Road,” a project that provides publicly accessible natural gas fueling stations, mainly for heavy-duty fleet trucks, along the 600-mile, Toronto to Rivière-du-Loup (Quebec) highway corridor. The “Road” now includes two publicly accessible stations and three installed by businesses for their own use. Gaz Métro expects the project to expand to five public stations by 2016.

The system now dispenses conventional natural gas as well as the small fraction from EBI. Gaz Métro plans to add RNG from several projects now at various stages of development. One of them is at an anaerobic digester to be built in Rivière-du-Loup, a town east of Quebec City. The digester, to be operated by the Société d’économie mixte d’énergie renouvelable de la région de Rivière-du-Loup (SÉMER) and using residential organic wastes as a feedstock, is expected to produce 3,000 cubic meters of liquefied RNG annually. Gaz Métro has announced that it intends to acquire the entire output for 20 years.

Once RNG from these projects enters the pipeline grid, truckers filling up at any “Blue Road” station will be able to opt to pay a premium for a share of the RNG. The cost and other details have yet to be determined, Gaz Métro says. However, the combined RNG and conventional natural gas is expected to be cheaper than diesel.

RNG Projects In Planning

Surrey, British Columbia

Surrey, a suburb of Vancouver with a population of 500,000, is proceeding with plans to convert 88,000 tons/year of organic wastes into RNG, which will fuel a new fleet of 52 garbage trucks, owned by Progressive Waste, which collects the municipality’s refuse and recyclables. Surrey was the first municipality in Canada to require use of natural gas-powered trucks in a request for proposals for curbside collection. This was an important first step in positioning the fleet for future use of RNG.

The City of Surrey, British Columbia is proceeding with plans to convert 88,000 tons/year of organics into RNG, which will fuel a new fleet of garbage trucks owned by Progressive Waste.

Photo courtesy City of Surrey

The city recently short-listed three companies, out of 11 applicants, to compete for a contract to design, build and operate the $68 million anaerobic digestion facility. The final selection is expected this fall, with construction to start next year for a 2016 opening. Surrey is to provide half the feedstock through yard trimmings and a residential curbside collection program it began two years ago. The operator will acquire the rest of the source separated organics from the industrial, commercial and institutional sectors.

The trucks, powered by natural gas, were purchased last year to replace diesel vehicles. As in the other Canadian projects, they won’t be directly fueled with RNG. Instead, the RNG will be added to the pipeline grid operated by FortisBC. The company will pay for the amount it receives — likely far more than the trucks require — and Surrey will pay for what it consumes. FortisBC will be able to sell any excess gas through the program, described above, that lets its customers volunteer to pay a premium price for RNG for home heating and cooking. Decisions on technology, equipment and financial arrangements are yet to be made. “Much of how that will play out will be determined through the procurement process,” says Rob Costanzo, Surrey’s deputy manager of operations.

The project was spurred by a 70 percent waste diversion mandate and a ban on organics in landfills imposed by the Metro Vancouver, which includes Surrey, Vancouver and 22 other municipalities on BC’s Lower Mainland. It’s expected to eliminate 23,000 metric tons annually of carbon-dioxide emissions, more than enough to offset Surrey’s total annual corporate emissions of 16,000 metric tons. This will let the city eliminate payments to the province’s carbon tax, now $30/metric ton, and earn carbon credits if they are ever implemented.

Woodstock, Ontario

Near Woodstock, in southwestern Ontario, five partners are developing Rural Green Energy, a project that will use manure from 1,500 head of beef cattle as the main feedstock for a system to produce compressed RNG for their trucks and farm equipment. The partners include a beef farm, a gravel pit operator, pork feedlot and hauler, custom farm and a dairy farm. All the partners have vehicles or equipment that run on natural gas and have agreed to replace some of it with RNG. Funding is being provided by Growing Forward 2, a federal-provincial program that encourages innovation, competitiveness and market development in Canada’s agrifood and agriproducts sector. Stonecrest Engineering is consulting on project development.

The anaerobic digester will be located on the beef cattle farm. The fueling station “will be a kilometer or two away, depending on what site works best in terms of access to the pipeline grid and for those who need the fuel,” says Nicholas Hendry, who is affiliated with Stonecrest and its sister company, Faromore, Inc.

The feedstock will also include spillage from organic matter fed to the cattle to ensure there’s enough to keep the digester operating at full capacity. Project costs remain to be settled, adds Hendry.

The partners may not buy the actual RNG produced at the facility. Instead tentative plans call for the biogas to be upgraded, pressurized and injected into the pipeline grid where it will join the flow of conventional natural gas to anywhere in North America. As with the other proposed Canadian projects, they’re paying for a certain amount of RNG whether or not it’s actually in the natural gas they get from the fueling station; a proportional amount of conventional natural gas is displaced in the distribution system. While RNG is more expensive than conventional natural gas, the partners will buy it only as a small percentage of their fuel so the price premium won’t be large. Any excess RNG production could be sold to other local bulk customers.

The project has also applied for a provincial Feed-in Tariff contract, for an electricity generator with a capacity of 250 kilowatts. If it’s approved, the amount of biogas upgraded to RNG may be reduced, while maintaining the proportion of it in the fuel sold to the partners.

Elmira, Ontario

Bio-en Power Inc. is conducting feasibility studies for an RNG fuel facility at its biogas site near Elmira, a rural community about 75 miles west of Toronto. The aim is to start with a pilot project that would fuel 6 to 12 waste trucks contracted by the local municipality, the Township of Woolwich, explains operations manager Earl Brubacher. The RNG would be injected into the Union Gas pipeline system, and the truck operator would pay a small premium, not yet determined, for the amount it’s deemed to buy.

“We’ve put the numbers together,” says Brubacher. “Now we need to find a customer willing to pay the premium.” That would likely depend on the municipality giving a higher rating to bidders with natural gas trucks, and offering to purchase RNG. “More and more municipalities are looking at natural gas,” he notes.

The RNG would be upgraded from biogas produced at Bio-En’s Elmira anaerobic digester facility, designed by the Austrian engineering firm Agrinz Technologies, and now in the final stages of commissioning. The company has installed 2.85 MW of generating capacity at the site and expects to start producing electricity in a few weeks, under an Ontario Feed-in Tariff contract. “The RNG is another alternative to the FIT contract,” Brubacher says. “We’d try to do both FIT and RNG.”

Peter Gorrie is a Contributing Editor to BioCycle.