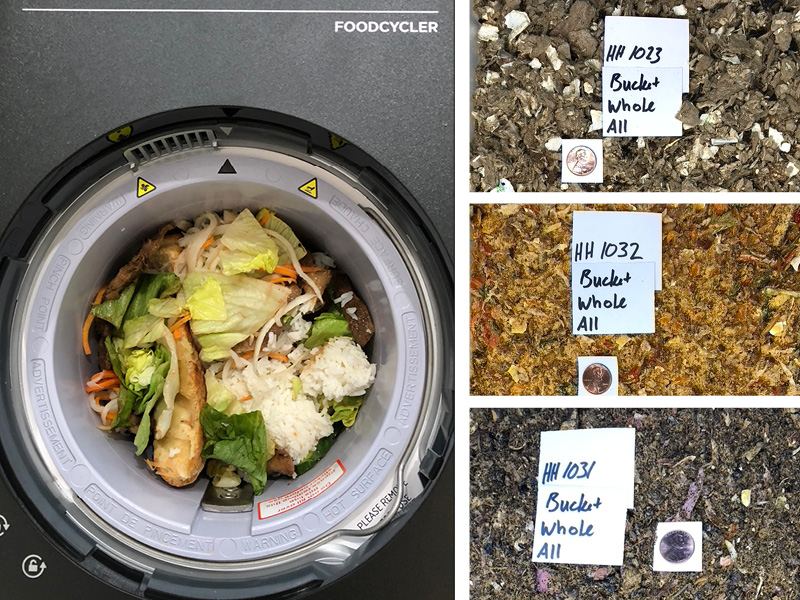

Top: A grind and dry unit turns household food scraps (left) into a dehydrated, stable-if-not-rewetted material (background).

Sally Brown

Sally Brown

The latest revolution in our industry comes not from the pages of this venerable journal but from Wired. Founded in 1993, Wired is where I go to read about the latest and greatest in artificial intelligence, not organics diversion. The focus of this magazine is how emerging technologies impact culture, economics and politics. That screams smart buildings to me and not static piles. But a recent article that showed up in Wired suggests that a revolution may be approaching.

It seems that many people, including the ones that read Wired, have figured out that diverting organics from landfills is a really good thing. The passage of the organics (SB 1383) bill in California has been a big help in drawing a lot of attention to this issue. A number of states have now passed measures to take organics out of the landfill. The newest is my own state of Washington where our governor just signed 1799. This bill mandates a 75% reduction in organic waste by 2030 with communities of 25,000 or more now required to offer collection. All great except how do you succeed? Here in very green Seattle, we’ve had cocollection of food scraps and yard trimmings for well over a decade. Participation rates are still under 50% and contamination is the norm rather than the exception.

The question has become how to get it done rather than whether or not it should be done. To date the philosophy has been give out the green bin and the informational handouts and cross your fingers. Outreach, some excellent ads, and the threat of fines have not changed the paradigm. If you were naïve enough (I was) to think that compostable plastic bags and those lovely little buckets were enough to facilitate behavior change, think again.

Now we see reviews of fancy machines in Wired. These machines suggest that the “how” is making the path from the municipal to the consumer products arena. In other words, making the transition from a good idea to an action facilitated by a fancy, non-municipal product.

The Devices

The Wired product reviews may portend a revolution. The article talks about home “composters.” Based on the manufacturers’ claims, home composting has made it out of the bin and into an appliance that turns your food scraps into “compost” right in the comfort of your own kitchen. Four newly available units are rated, ranging in price from $300 for the Vitamix Food Cycler to $499 for the Pela Lomi. The highest rated device, the Reencle, is on preorder for $439 but will eventually retail for $699. BeyondGreen’s Kitchen Waste Composter retails for $430. Two of these devices actually decompose the food scraps, or claim to. The other two (Food Cycler and Lomi) dry and grind.

All look sleek and fit well either on or under your counter. They do the work for you. No more fretting about particle sizes for your kitchen worm bin. The machines also all take away the slime and the smell — at least they claim to.

I can talk about the potential for success for the two that actually “compost” based on my knowledge of the processes involved. My knowledge also tells me neither should be categorized as composting devices (pre-composting might be more accurate). I can talk about one of the devices that dries and grinds from first hand experience. Let’s start with the two that claim to compost. Reencle is based on the bokashi system — acid anaerobic fermentation. This is the highest rated device and the priciest. I worked with material from bokashi systems and have written about it in BioCycle. The Wired review notes that sometimes when you open the device, you get a whiff of a nasty smell and that sometimes the decomposition can go wrong. The reviewer says however, that you can hit the “dry” button to reset and restore the device and that there is also a “purify” button to get rid of any odor. He says that his unit worked “flawlessly.”

Soil was blended with bokashi that was months old (left) and used in kale growth trials. Pots without any growth are the bokashi blend. The yellow sticky paper (center right) is catching bugs attracted by the bokashi. Photos by Sally Brown

The bokashi that I know is not for the faint of heart. It is a very smelly process that reduces the volume of food scraps but in no way produces a stable material that is useful as a soil amendment. We mixed finished bokashi material (stabilized for months and not days) with soil and let it stabilize and decompose for several months before we planted seeds. Those seeds never germinated and the stabilizing mixture smelled terrible and attracted flies for weeks. It was only months later with the second planting that we saw growth in some of the pots. In other words, a great idea that maybe works in the house. As a soil scientist, I’m not sure at all how it could work in your yard — unless very small amounts are scattered across a wide area or material is further treated in soils or in a second device as yet to be reviewed in Wired.

The second option is a BeyondGreen Kitchen waste composter that comes with wood chips and baking soda. The reviewer says that it has a smell and makes finished compost in one week. The reviewer also says that the finished compost has “chunks of food and larger bits in there.” Any self-respecting composter out there who can make compost in one week? I didn’t think so. Here it is highly likely that the decomposition process has started. For the patient or willing homeowner/gardener, they will understand that burying the material after mixing it with soil — same as with the bokashi-esque device — will help your soil over time. But patience before you plant the petunias. Another warning sign on this one is the odor comment. No one wants a stinky kitchen.

Dry And Grind

Then there are the two devices that dry and grind your food scraps. These machines require you to fill them up before you turn them on. Once on, they take several hours to dehydrate your food scraps. The instructions for both devices say you can add the finished material to your soil. Although not in the instructions, addition to soil would need to be at “season to taste” rates or you have a high potential for mold, insects and rodents.

We had a FoodCycler for several months before we managed to bust it. It felt like having a mini miracle on our patio. The dried material has minimal odor (except when my husband cheated and put dog poop in it) and is 100% free of any yuck factor. It made it very easy to put the food scraps in and end up with a nice almost powder-like material in just a day. Once the material is rewetted, decay with the associated slime and mold and smell will start almost immediately. Critters that think that slime smells sweet will come. But for the homeowner, all of a sudden organics diversion is easier than operating a home espresso machine.

Paradigm Shift?

Each of these devices represents a sleek alternative to the green bag and bucket. Each of these includes design features and options that have been foreign to our industry for its entire lifespan: Nice to look at, fits on or under the counter, has a fancy computer interface. Each reflects a paradigm shift both for the designer and the consumer.

None of the devices reviewed in the Wired article produce a material that would stand a chance for the US Composting Council’s Seal of Testing Assurance (STA) compost certification. That is OK. The critical part of all of these things is that they offer a vastly different approach that has the potential to truly disrupt and change the system — for the better. Instead of focusing on the problems with each of these devices or the claims that are a very long stretch from reality, consider the potential. Realize also that these are the first in what is likely to be a range of products, all designed to get the average person to take food waste out of the garbage.

At the very least, and speaking from personal experience, these are user friendly devices that have a very high potential to increase participation rates in food diversion programs. For the dry and grind models in particular, they take the urgency out of food scraps diversion. No need for you to try to gather the slimy plastic bag filled with scraps and carry it to the appropriate bin, all the time filled with terror at the potential for a bioplastic bag failure and the clean-up that it would entail. The dried materials can go into a paper bag or any other type of container and stay put (if kept dry) until you are ready to take a trip to the green bin. Contaminants that you mistakenly put in the device would either bust it or rise to the top. Nothing like first-hand experience to facilitate behavior change. If these devices, deployed on a large scale, can up participation and reduce contamination, that is a big win all around. The fact that the material gets reactive on contact with water and starts to smell is much less of an issue if it happens in the collection vehicle on the way to a processing facility (e.g., composting, anaerobic digestion) instead of the kitchen.

In the most revolutionary sense, these machines have the potential to greatly reduce if not eliminate the need for centralized collection of food scraps. Straight from the kitchen to your yard is as circular as it gets. If you consider that as a potential, the price tags don’t seem so high. If people get and use these devices, collection frequencies can be reduced. Municipalities can meet state mandates and have a big, positive impact on climate change.

Considering each of those, it might be cheaper for your local municipality to buy you one of these rather than expanding their fleet. These slick devices, are hopefully the start of an organics upheaval. I’m sure that perfected devices that really produce compost won’t be far behind.

Sally Brown, BioCycle Senior Adviser, is a Research Professor in the College of the Environment at the University of Washington.