Anticipated disposal ban on commercial and industrial organics is expected to be added to the state’s existing ban structure. The more pressing issues are ensuring robust generator training and hauling and processing capacity are in place to manage the materials. Part III

Zoë Neale

BioCycle April 2013, Vol. 54, No. 4, p. 34

The Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) continues to push forward on modification of its existing waste ban structure to include industrial and commercial organics. Last year, DEP streamlined its regulatory framework for siting new processing capacity in the state, explicitly allowed wastewater treatment facilities to accept source separated organics (SSO), and took steps to facilitate the building of anaerobic digestion (AD) plants on state property (see “Massachusetts Sets The Table For An Organics Ban,” December 2012). The DEP continues to draft the solid waste regulatory package that covers the ban. It conducted almost two years of informal meetings about the regulatory package and the organics ban under the aegis of the Organics Subcommittee, and received a prodigious amount of input from a broad range of interested parties.

While the solid waste rule package has not been released for formal public comment, many of the details have been discussed in the Subcommittee meetings, providing industry participants with a fairly good idea as to the structure. The regulation amendments are expected to be fairly straightforward as organics will simply be added to the existing ban structure as another banned material. The real substance, though, will be in the accompanying revised waste ban guidance document for solid waste facilities and businesses, institutions and haulers. The guidance document will contain all of the most critical implementation specifics on the ban for generators, haulers and processors, making it the most important document that the DEP will generate.

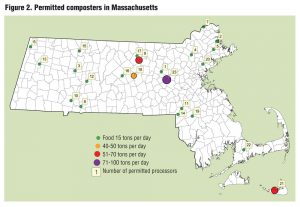

The impacted market participants’ main concern is based on the disconnect between the amount of SSO the DEP has stated it expects would be incrementally captured by the ban (350,000 tons/year) and the lack of available capacity to process it. Currently, there is approximately 150,000 tons/year of nonlandfill, nonincineration permitted food residuals processing capacity in Massachusetts, not including pig farms, on-site management or use of garbage disposers. Of Massachusetts’ 221 active composting facilities, only 23 are permitted to accept food residuals. Simply adding food to the other 198, mostly municipal leaf and yard trimmings composting sites, is a challenge that most operations are simply not equipped to effectively manage.

It is the DEP’s assumption that by imposing the waste ban on generators of over 1 ton/week of organic waste that, along with regulatory streamlining, favorable market conditions will follow that support development of necessary and substantial amounts of new in-state processing capacity. Upon conducting interviews over several months with multiple generators, haulers, composters, AD developers, municipal recycling coordinators, state employees, consultants and industry insiders, Part III of this article series examines these assumptions through the lens of current market realities.

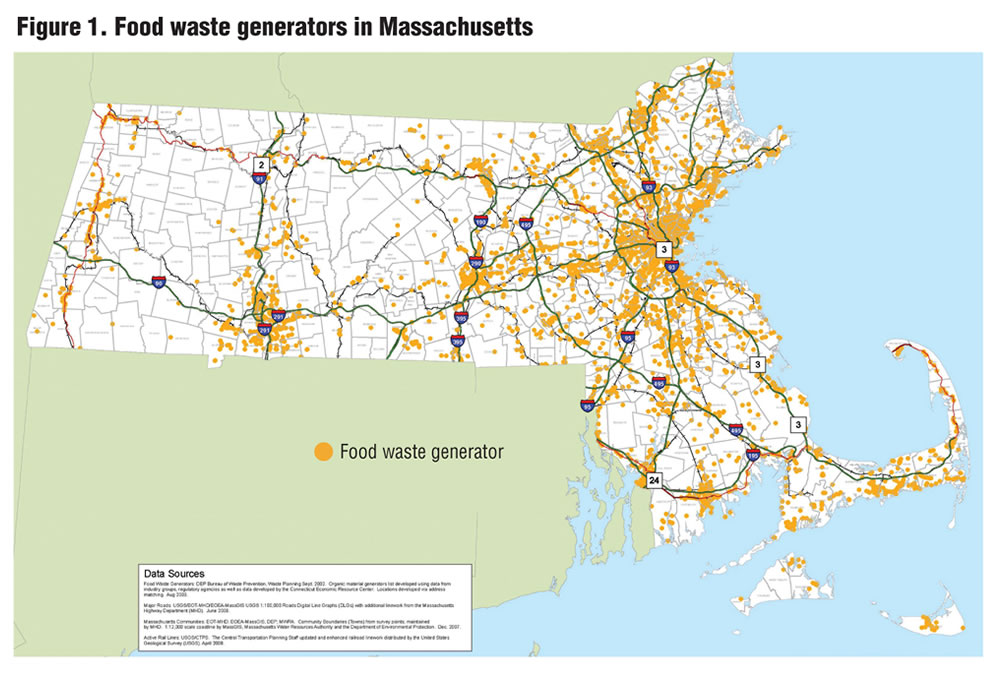

Devil In The Details

To understand the opportunities and challenges of implementing the organics ban, the first step is to examine the core data on which the state’s empirical volume and generator assumptions are based. The original analysis, commissioned in 2002 by DEP to assess statewide volumes of food waste generated, was conducted by Draper-Lennon, Inc., a New Hampshire-based consulting firm. The assessment, “Identification, Characterization, and Mapping of Food Waste and Food Waste Generators in Massachusetts,” included a database of food waste generators, an estimate of food waste generation volumes and a set of Geographic Information System (GIS) tools that were intended to aid developers of organics processing facilities by informing them of the locations of feedstock streams (Draper and Lennon, 2002). In the report, 6,861 food waste generators were identified producing approximately 950,000 tons/year of organic waste (Table 1).

A number of significant caveats surround the data. These include: 1) Analysis was conducted using a factor-based algorithm developed from surveys of SSO generators that appears to have utilized few real-world statistical samples to check the accuracy of the data; 2) In a recent update to the original report, which is over 10 years old, the majority of the data has not been revised; and 3) Estimates for the food and beverage manufacturers/processors and food wholesalers and distributors, which, combined represent almost 65 percent of the total annual food waste generated (1,336 facilities generating a total of over 620,000 tons), do not include facility specific data. Instead, it is a sector wide estimate subject to substantial variance. Clearly, the third point is most problematic as the key purpose of the project was to develop a detailed database of the major food waste generators. Recognizing this fact, the DEP is currently working on revising the factors in order to improve the accuracy of this very important data set.

Finally, even if the factors developed and utilized in 2002 were fairly accurate, business practices have evolved significantly over the last decade, especially in the area of food processing. Specifically, much of the processing occurring on-site (especially for meat and poultry) a decade ago now takes place at locations where labor and land rates are considerably lower, leading to less food waste being generated in the processing industry regionally. Taken as a whole, the 2002 Draper-Lennon study represents, at best, a very preliminary starting point in the process of determining locations of significant amounts of available food waste that a large-scale developer needs to secure for project development.

Industrial And Commercial Generators

Successful implementation of Massachusetts’ organic waste ban relies on compliance by larger generators subject to the ban that are not already source separating. As mentioned, the Draper-Lennon report does not address this issue although there is little doubt that many of the larger producers of organic waste are already source separating as a cost mitigation strategy. The ban’s success is reliant on awareness by generators that it exists and whether or not the ban applies to them. Outreach by the DEP to the generators has consisted of funding the Recycling Works program, presenting at various conferences and meetings and the Organics Subcommittee meetings. It is difficult to ascertain the overall level of awareness by generators not already source separating. In its communication with generators, DEP contends that separating organics should save generators money by reducing their trash hauling volume, i.e., total cost (hauling plus tip fee) is less for the organics portion of the waste stream than for MSW.

This scenario only applies if the generator is paying a relatively high cost for mixed trash disposal and also reflects a demand level for organics processing that is still relatively nascent. The cost-benefit analysis of source separating is critical as few waste generators are willing to pay more purely for environmental or societal benefit. Hauler interviews and waste characterization studies conducted at various businesses combined with anecdotal examples indicate that the very large restaurant sector has a relatively low current penetration rate of actual source separation of organics. On the other hand, restaurants are comfortable with recycling grease, which has a commodity value and can actually generate a small revenue stream (similar to paper and cardboard). Often more prohibitive for restaurants is the internal challenge of implementing a SSO program. These include limited space in the kitchen for additional barrels, minimal outside room for an additional dumpster, sanitation issues related to SSO storage, and the hard costs of training, implementation and compliance. There is also a perception that separating food waste should generate a “credit” from their hauling company (not unlike the model for grease or cardboard) although this is not the reality in the market. Finally, restaurants are unclear as to whether or not the ban will apply to them, increasing the need for more aggressive DEP outreach.

Processing Capacity

Current infrastructure for processing SSO (other than combustion and landfill) in Massachusetts is comprised of 23 permitted food residual processors with a combined capacity of 150,000 tons/year. The largest permitted facility is a 100 tons/day mixed waste cocomposting facility in Marlborough operated by We Care Environmental. The second largest is a 70 tons/day composting facility (Mass Natural Fertilizer Company) in Westminster, which is over 50 miles from Boston. The third largest, at 60 tons/day, is located on the island of Nantucket (operated by Waste Options, Inc.).

Many composters interviewed for this article series have similar perspectives on the issue of clean, contaminant-free feedstock — mainly that’s it’s getting more and more difficult to find. One larger processor interviewed will only accept industrial organics and will not consider commercial sources due to the difficulty in ensuring feedstock continuity. From an end product quality standpoint, contamination is a major problem. It not only can erode the value of the compost products, but can cost the operator approximately $80/ton to dispose of the material versus an average $45 to $55/ton tip fee received. This dynamic is most apparent at the composting facilities close enough to major generation hubs. Recognizing that demand for their facilities will only increase, the composters have stepped up their internal quality controls by carefully inspecting all incoming loads. When contaminants are found, the operator does not hesitate to reject the “dirty” load, which in turn leads to the organics being physically reloaded onto the truck and taken elsewhere — obviously a very costly and unattractive outcome for the hauler.

Eyes On Industrial Scale Anaerobic Digestion

Throughout the process of putting an organic waste ban in place, the DEP has publicly stated that through policies and other measures, it is looking to create an environment that is conducive to private development of multiple large-scale anaerobic digestion facilities in Massachusetts. This is understandable as a typical industrial scale AD facility is designed to process 100 to 150+ tons/day or approximately 50,000 tons/year. Clearly, with the DEP targeting 350,000 tons of organics that need to find a home, large-scale projects like AD play an important role in meeting diversion goals while also having the added benefits of renewable energy production, a marketable end product, and greenhouse gas mitigation. While the political will most definitely favors anaerobic digestion, the economic returns remain challenging for a number of reasons — including low natural gas and energy prices.

The most critical components of a successful, large-scale AD project can be summed up in three words: financing, facility and feedstock. From a capital and funding perspective, there is evidence that the venture capital community is deprioritizing renewable energy, including anaerobic digestion. Several investors interviewed cited the mismatch between the return and timeframe structure of venture capital funds (typically a 7-year return horizon with triple digit potential returns) and AD projects, which have a much lower rate of return over a much longer time horizon. In terms of traditional debt financing, banks continue to be extremely risk-averse and have not been players in the nascent bioenergy industry.

Other than the digester operating at Jordan Dairy Farms in Rutland, Massachusetts, developed by AGreen Energy, only one facility — a NEO Energy project in Fall River— is in late stage due-diligence (has purchased property, begun initial permitting, etc.). This project, originally slated to process 55,000 to 60,000 tons/year of food waste, recently announced its intention to reduce the capacity by nearly two-thirds, to 20,000 tons/year. Another possible project in Bourne (on Cape Cod) is in negotiations with a developer although the details have not been released. It appears at this time that DEP’s goal of three AD facilities in the state by 2014 (see Part I of this article (December 2012)) will not be met although the DEP is doing everything it can to assist with project development through elimination of site assignment and through funding of feasibility and technical studies. Also, the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center has recently awarded $400,000 in construction grants to two more farms in western Massachusetts that are affiliated with the dairy cooperative that includes Jordan Farms.

Path Of Least Resistance: Wastewater Treatment

With the anticipated effective date for the commercial and industrial organics ban a little more than a year away, and little new composting or anaerobic digestion capacity on the horizon, the DEP is eyeing existing AD capacity at wastewater treatment facilities as the proverbial “path of least resistance.” One facility in particular is being targeted for its potential to take SSO — the huge Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA) plant on Deer Island in Boston Harbor. To this end, the MWRA is expected to issue an RFP for a three-year pilot project that would utilize one of the existing eight digester “eggs” to determine the feasibility — across its system — of adding SSO. The benefits of digesting the SSO with biosolids (other than utilizing existing infrastructure) include potentially higher gas, electricity and heating yields.

However, there are several significant questions regarding the impact SSO would have on overall operations: 1) Cost-effective transport of the SSO feedstock to Deer Island, which would need to be introduced to the digesters in slurry form; 2) More residuals would be generated and need to be processed with a still uncertain understanding of the impact on the quality of the pelletized biosolids product; 3) What costs would be incurred to upgrade the combined heat and power (CHP) unit; and 4) Effect on nitrogen and phosphorus levels, which is particularly important as the outflows are pumped into the Atlantic Ocean, a rich fishery.

While the proposed pilot will provide a wealth of critical information regarding the viability of this concept, the MWRA Board is very clear that adding SSO to the existing operation needs to prove to have tangible economic benefits for consideration of a full rollout. This would include charging a tip fee to the provider of the feedstock. Clearly, proving the viability of Deer Island for processing of SSO remains in a very early stage.

Onus On The Haulers

Throughout the process of discussing and forming revisions to the current waste ban structure to add commercial and industrial organics, there has been a consistent message from the DEP to the hauling community about implementation of the ban: “The onus is on you.” The haulers are seen as the direct connection to the generators, thus by default the responsibility falls to them to determine whether or not a given customer is subject to the ban, communicate specifics of the ban to their customers, price the service, help the client put processes in place to separate organics from recycling and mixed waste, and last but certainly not least, ensure compliance. Ensuring customers are following protocols that lead to “clean” organics loads is clearly a substantial challenge. Maintaining client relationships is critical in this highly competitive industry, and many haulers expressed concerns about antagonizing customers who may take their business elsewhere.

Economics of SSO diversion are directly affected by the density of pickups on the collection route, proximity of the transfer or processing facility to the collection routes, and the ability to keep contaminants to a minimum. Furthermore, separated loads of organics, especially food waste, are heavy, which can limit the total amount per load due to weight limits. Because hauling of SSO is still in its infancy in Massachusetts, infrastructure to support it — not just processing capacity but route density and transfer stations — are not yet in place. Operationally, servicing organics customers entails fairly frequent pickups and utilizing separate trucks from MSW and recyclables. Organics collection trucks often require higher levels of maintenance due to the heavier nature by volume of the substrate. While developing the framework for the ban, DEP’s assumption is that the ban will create higher levels of route density and profitability as the demand for hauling SSO increases.

Conclusions

Throughout the process of conducting interviews for this article, many industry participants had opinions regarding the upcoming organics ban. One of the most consistent criticisms is that the DEP is not effectively enforcing the 13 existing waste bans (see Part I) due to staff shortages. In response to this input, the DEP was recently approved to fill three new inspection and compliance positions, two of which will also involve outreach and communication on waste bans. These new postings not only significantly enhance the agency’s ability to enforce existing and future bans, they also help to address the second most frequent concern raised by the industry — proactive communication with the large number of generators that will be subject to the ban. This aspect is of particular importance to the haulers as it takes the burden off of them to communicate a state mandate to their customer base. Comprehensive generator communication would also help improve diversion rates and compliance capabilities at solid waste facilities where organic waste is expected to be identified and failed load letters are issued to haulers.

The most difficult aspect to solve is the lack of viable processing options for the expected volume of material. Many industry participants feel that as a result of the capacity mismatch, it would be prudent for the DEP to alter its existing approach. Several alternatives have been mentioned by multiple industry participants including: 1) Raising the generation tonnage that the ban would apply to (10 tons or more); 2) Mandating source separation and composting for large generators if there is a processing facility within a “reasonable” distance — akin to the state of Connecticut’s approach that requires large-scale commercial generators of food waste (defined as generating more than 104 tons/year or about 2 tons per week) to recycle source separated organic material, once permitted capacity is available; or 3) An incremental approach similar to Vermont’s Act 148 that bans all food waste from disposal by 2020, however different sectors will have to comply in different years (e.g., generators producing more than 104 tons/year by 2014, followed by generators producing more than 52 tons/year in 2015. Any of these alternatives would give developers more time and perhaps more positive incentives to build the necessary capacity for substantial organics diversion.

Although supportive of creation of the elements critical for development of crucial infrastructure needed for large-scale organics diversion, the DEP and other state agencies are limited in ways they can influence private markets. Given economic conditions and returns necessary to justify the substantial capital outlays by the private sector, it may be prudent to take an approach that is perhaps more incremental and better suited to the current challenges surrounding successful implementation of an organics ban.

Zoë Neale has spent the bulk of her career as an equity mutual fund manager and advocate for socially responsible investment. She currently works as a business consultant and is a founder and director of Save That Stuff Organics, an organics solutions affiliate of Save That Stuff Inc. Zoë is Treasurer of MassRecycle and chairs the Organics Committee for that organization.

Reference

Draper D. and M. Lennon. (2002). Identification, characterization, and mapping of food waste and food waste generators in Massachusetts. Boston, MA. Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection.