Top: Inset images (from left to right): Common apartment building set up with trash (grey lid), recycling (blue lid) and organics (brown bin); Mixed plastics and organics in trash bag; Brown organics bins in typical apartment storage area. Background photo: NYC Sanitation Department truck collecting leaves set out in clear plastic bags in suburban neighborhood. Photos courtesy Samantha MacBride

Samantha MacBride

In late 2022, New York City launched a new, and what it described as simplified, curbside organics collection program in the Borough of Queens. Under the old program, residents had to use New York City Department of Sanitation-issued (DSNY) brown bins or paper leaf bags for their setouts. In the new program, they can use any type of labelled bin with a lid (up to 55 gallons in size) — which is consistent with setout requirements for curbside recycling that have been in place for decades. All food waste, food-soiled paper, and leaves and yard trimmings are accepted. For extra yard trimmings, residents can use clear plastic bags. In 2023, the entire Borough of Brooklyn was added to the program, with the remaining Boroughs (Manhattan, the Bronx and Staten Island) set to come on board in late 2024. New York City Mayor Eric Adams and Sanitation Commissioner Jessica Tisch have promised to get composting done, after a decade of failing efforts at curbside organics collection.

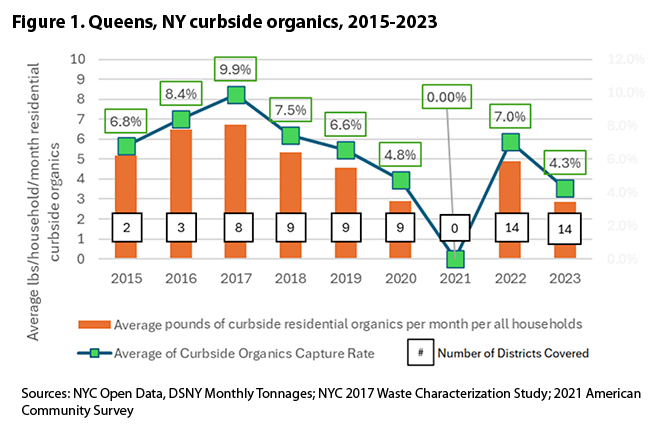

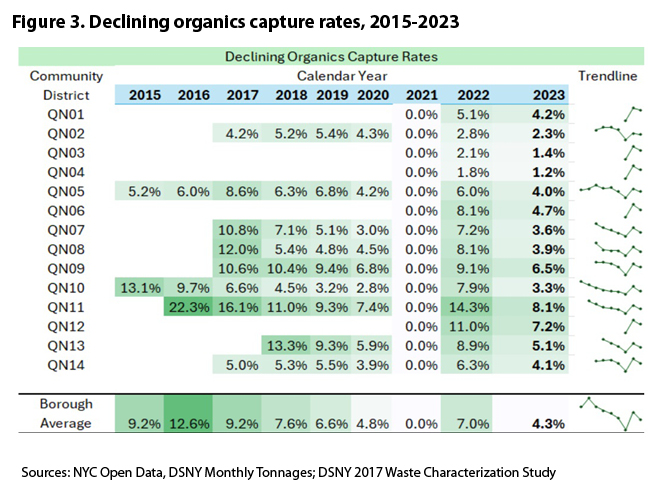

Queens has had the program for a full year as of January 2024, making analysis of its performance useful in assessing how the rest of New York City (NYC) will perform as the program expands. Unfortunately, Queens’s capture rates have declined over the past 10 years, as has the quantity per household of organics that are set at the curb. For 2023, the residential curbside capture rate was 4.3%, down from 7.5% in 2018, when 9 of the 14 Queens Districts had been brought into the collection program. Prior years (Figure 1) show even higher capture rates, although they reflect fewer districts.

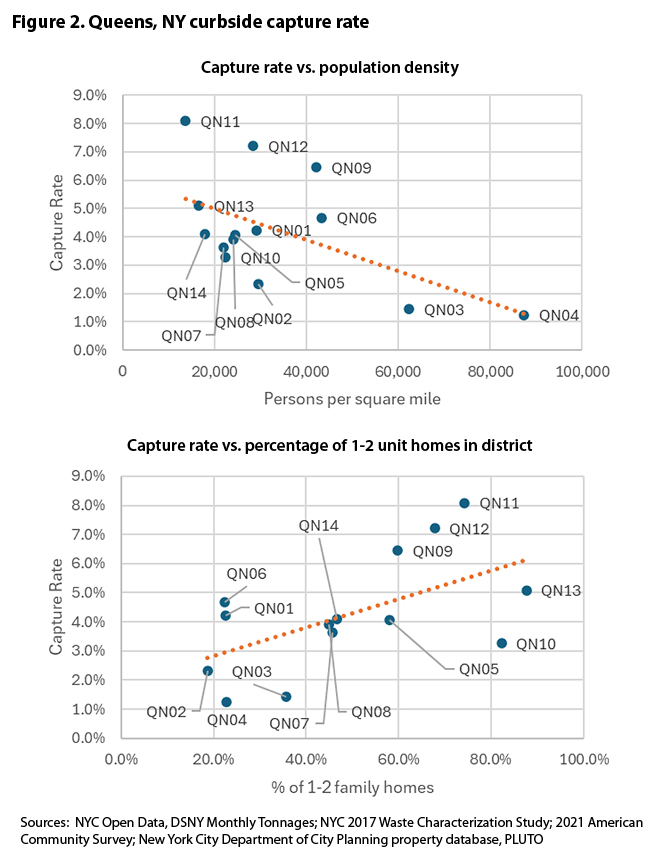

The single-digit capture rates are dangerously low for a program that has been piloted, expanded, paused, cancelled, and restarted over a decade in NYC. To date, city officials have not publicly discussed this decline. Furthermore, it’s unclear if they have considered important implications of variations in performance in different districts of the borough. The scatterplots (Figure 2) show the distribution of the 14 current Queens districts by predominance of population density as well as by one- to two-family homes. The trends are notable, and consistent with prior years.

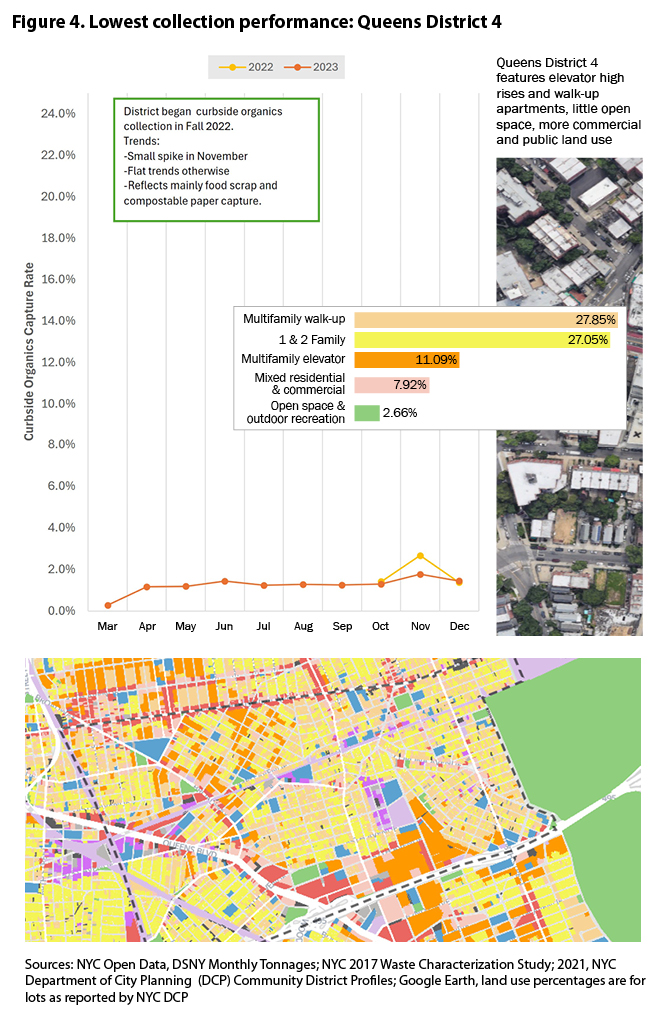

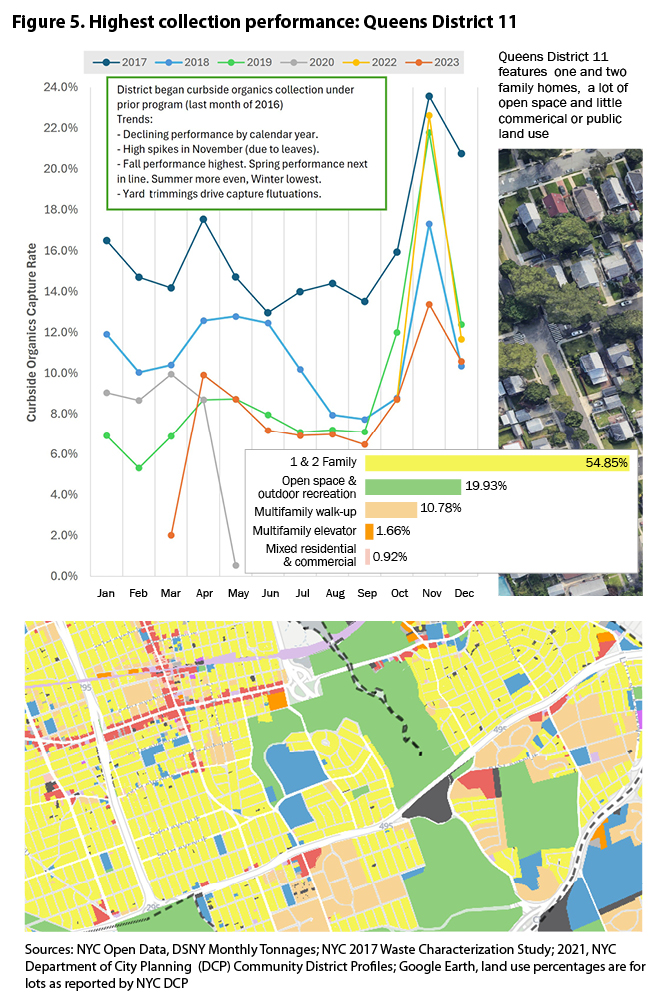

Queens Districts 9, 11 and 12 are suburban-style districts in the eastern part of Queens, which borders Long Island and have lots of one- to two-family homes with trees and lawns. They showed capture rates exceeding 6% for 2023, and in the fall months, a few hit double digit capture rates. Queens Districts 3 and 4 are in the western part, where apartment buildings on smaller lots predominate. Their capture rates hover around 1%, hardly deviating throughout the year. Other districts fall in between.

These variations point to issues in two related areas: the role that yard trimmings play — with inclusion of food waste — in program success, and the considerable challenges to participation in apartment buildings, as opposed to suburban style homes. The takeaways are relevant to residential organics collection managers in jurisdictions around the country and elsewhere.

Background

The City’s previous curbside organics program ran in only some of NYC’s 59 Community Districts between 2013 and 2020, when the program was cancelled. The number of Districts served increased year by year starting in 2013 through 2018. Then, amid publicized success, further expansion was halted for budgetary reasons. At the time, 15 Districts in the Bronx, Brooklyn and Staten Island, along with nine in Queens, were receiving curbside service. There were also special routes designed to pick up from apartment buildings in Manhattan and Southern Bronx. Overall, participation was low everywhere the program ran. Trucks did not fill up, and as a result collections were inefficient and costly. Collection continued in 2019 and through May 2020, when it was cut. Even without the pandemic, the program was not financially sustainable, and was not diverting more than tiny quantities of organics from disposal.

In Queens, the program was conceived to serve mainly 1–9-unit households. To be included in the program in any borough, buildings of 10 units or more had to complete a special application process that involved a site and training visit by DSNY staff, and ongoing phone and email support. Most buildings that volunteered were in Manhattan. Few did so in Queens. The new program that launched in Fall 2022 aimed to reverse that problem. All buildings, regardless of size, receive collection of organics without needing to enroll or undergo training. The new program made more geographic sense, covering the entire borough, including the five Districts that had not been included in the prior program (DSNY, 2022).

The same, simplified new program will be coming soon to the densest parts of New York City: Manhattan, and southern Bronx, where 10+ unit building predominate. Paired with these plans is expansion of Smart Bins, which allow residents to drop off food scraps, food-soiled paper and pizza boxes (no yard trimmings) in a kiosk that uses an app to unlock and lock. Over 400 of these bins have been placed citywide, with 44 in Queens. Although the city has not published borough specific, or even citywide, tonnages from Smart Bins, they are said to fill up regularly and are low in contamination. Currently, these bins are collected in the same trucks as food waste from New York City schools, which historically have shown much higher rates of contamination.

The return of curbside organics collection came with some disappointing news. In late 2023, the Mayor’s budget cut NYC’s Community Composting program as a cost saving measure. The New York City Compost Project, a 30-year-old partnership between DSNY and a network of community processors and educators, accounted for less than 1% of DSNY’s $1.9 billion budget. Sanitation officials explained the cuts, and the hopes for a new, more efficient approach through curbside collection, this way: “Composting programs work best when they’re easy, and the programs being implemented today are for everyone, not just the truest of the true believers” (Hilary, 2022). The “true believers” were the New Yorkers that the NYC Compost Project trained, educated, and involved in hands-on composting — which numbered in the tens of thousands annually. “Everyone” in Sanitation’s explanation, includes all 2.4 million residents of Queens, and eventually another 6.3 million folks in other boroughs as well.

Assessing Queen’s Curbside Organics Performance

At first, reports from DSNY seemed to augur success. Three months in, DSNY was reporting a total collection tonnage of over 12.7 million pounds, or around 6,400 tons, which it said “wildly outperformed” prior programmatic efforts (DSNY, 2022). Yet even in those first Fall months of 2022 when leaves are at their highest, the borough’s average organics capture rate of 7% did not reach double-digits. Fall 2023 performance was lower (5.4% capture), reinforcing a disturbing trend of decline seen in nearly every District in Queens. It appears that in the heady, early days of collection service, residents participate more. This held both for Queens as a whole, and individual Districts (Figure 3). A strong start petered out over time.

This is a concerning, and now recurring, trend in residential curbside organics collection in 21st century NYC: low capture rates that get even lower over time. What explains this? Ongoing public opinion surveys would be needed to definitively answer the question. Reasons might have to do with the need for more ongoing outreach and education, as many citizens groups point out. Furthermore, operational factors like missed collections and damaged/stolen organics bins, which were commonly reported problems among residents in the period 2013-2020, may have left residents disillusioned with a program they were initially excited about. Finally, fatigue with an on again, off again approach to curbside organics collection that characterized the last decade of service may have played a role. At the moment, all we have are anecdotal complaints from individuals about these aspects of the new program.

What is not anecdotal are performance trends measured in tonnages collected. There is no getting around the fact that the new, simplified program is not collecting much tonnage. Declining performance over time is one issue; a second issue is low performance to start with, which is marked especially in Queens Districts with lots of apartment houses and high rises. Multi-family buildings, by and large, don’t generate much yard trimmings. Districts in which multi-family buildings predominate (e.g., Figure 4, Queens District 4) show a far lower capture rate (just barely exceeding 1%) than do less dense, suburban-style zones (e.g., Figure 5, Queens District 11).

Food Scraps vs. Yard Trimmings Capture Rate

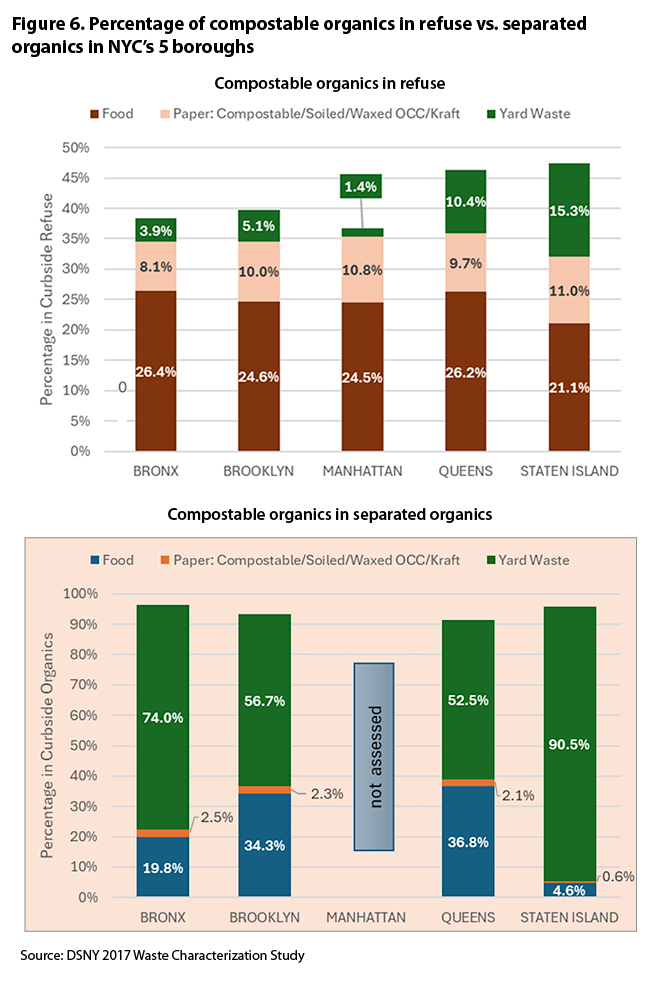

As BioCycle readers are aware, waste composition data is needed to calculate a capture rate as the calculation uses the quantity of organics in the trash stream. New York City is due to release a new waste characterization study in 2024 but has not yet done so. The most recent prior study was in 2017. It showed that in Queens, 53% of separated organics were yard trimmings, although this was early on in the prior program. This study also showed that Queens’ refuse, at that time, consisted of almost 47% of compostable organics, including 26% food waste, 9.7% compostable paper, and 10.4% yard trimmings. Results for all boroughs are shown in Figure 6.

Without an up-to-date waste characterization study, it’s not straightforward to calculate capture rates for subfractions of organics like food waste, compostable paper, or even yard trimmings when they are all collected on the same routes and reported as totals. The characterization of separated organics in the 2017 study was done early into the previous program, when only eight districts were served. Today, the spike in collections in the Fall, and the superior, while still low, performance of leafy, suburban style Districts in the eastern part of Queens, strongly suggest that yard trimmings play a pivotal role in boosting organics capture beyond the 1-2% level. In other words, the program’s high single-digit capture rates depend heavily on residential housing that generates leaves in the fall, and grass clippings and prunings in the spring. This finding does not bode well for the food scrap/compostable paper aspect of curbside organics.

The Multi-Family Building Challenge

As is experienced in jurisdictions with organics collection programs, most apartment building tenants participate anonymously because separated materials are deposited into communal bins. Apartment managers, trained in real estate and not sanitation enforcement, have limited ability to police tenants, although tenant lease clauses and proper signage and receptacle setup certainly can help. There is also the fact that food scraps generate odors and attract vectors if improperly stored in buildings before collection. It is often the case that apartment building infrastructure for waste management, such as chutes, is at best designed to handle recycling as well as refuse, but rarely is a third chute for organics added. The widespread use of compactors in apartment buildings encourages the seeming disappearance of trash, which is tough competition for bins or bags of decomposing food.

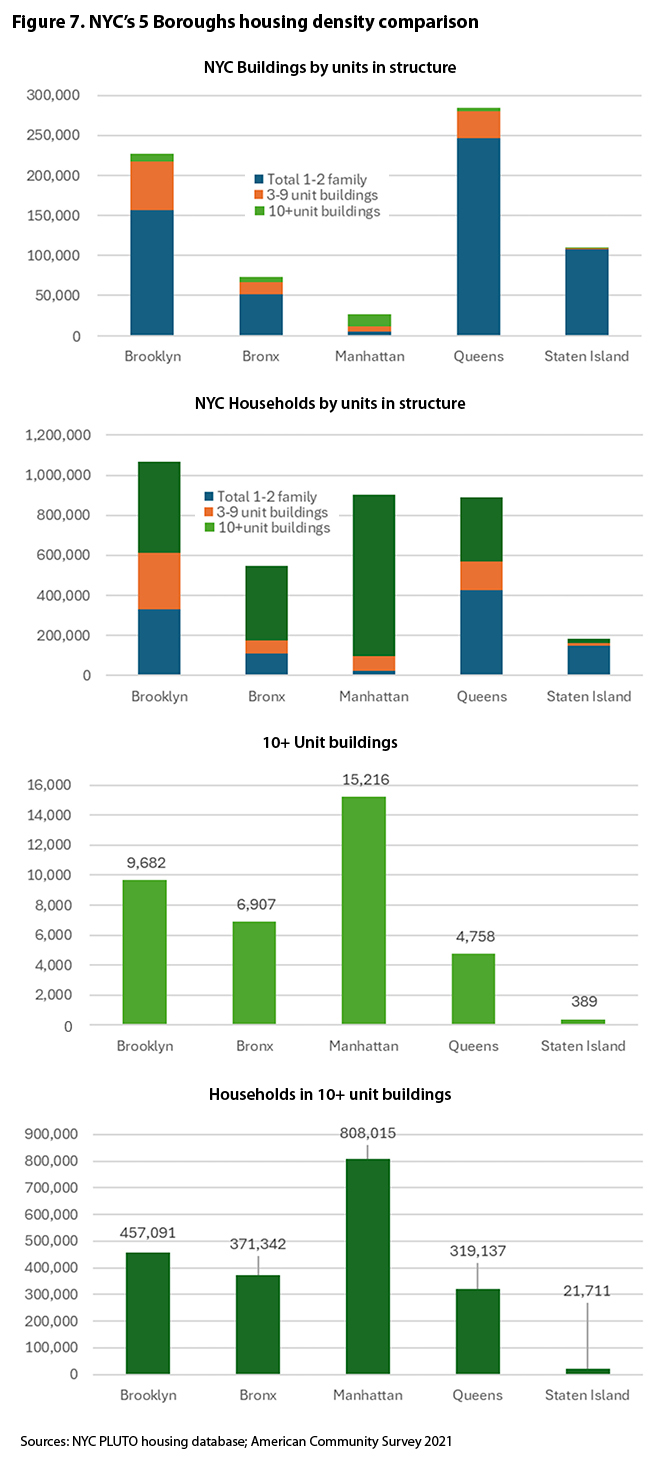

In NYC, this reality is particularly salient because of the sheer scale and proportion of housing. As shown in Figure 7, while the number of one- to two-family homes is higher than the relatively fewer apartment buildings, most households in NYC live in apartment buildings. And at the scale of NYC, “relatively fewer apartment buildings” number nearly 37,000 properties citywide. To train each building in the space of a year would require training over 100 buildings a day, seven days a week — a task that defies contemplation. At the same time, nearly 2 million out of the 3.5 million NYC households are in 10+ unit apartment buildings. They can’t be ignored. And these statistics just get bigger if we look at 3- to 9-unit buildings.

Despite the staggering numbers, the only way to address the issue of low performance in multi-unit buildings, and in Districts where multi-unit buildings predominate, is by offering coaching and resources to building staff and tenants. DSNY offers a general “Clean Buildings Training” certificate for owners and managers, but its reach, in terms of numbers trained, is not public information, and is by many accounts a drop in the bucket so far. Guidance must be given to buildings on the number of bins they need, and allowances made to use larger toters than currently allowed for space efficiency. Pickup of larger toters may require more of the automated collection that DSNY is experimenting with currently. Only some properties will be able to afford equipment to dewater the organics and reduce odors, but technical assistance in this area is needed as well. Overall, neighborhoods with lots of large apartment complexes may need more frequent collection than once a week, with a gradual phase out of three times weekly refuse collection that serves them now.

DSNY plans to launch enforcement, with ticketing and fines, in 2025, in multi-family buildings. Warnings will come before enforcement, but it is highly unlikely that most building managers and tenants will be able to abide by mandatory requirements, much less maximize the capture rate, without some advance guidance. Such attention takes time and money (in short supply due to budget cuts). It is not at all clear that city officials have thought through this problem fully.

What Transparent Reporting Looks Like

Achievements of the current curbside program must be understood in the context of the massive quantities of compostables that still go out in the trash. Omission of context was seen in the City’s early celebration of great success in Queens (DSNY, 2022). DSNY shared poundages of organics, which sound huge very quickly, even as small tonnages mount.

They calculated month-over-month increases in poundage as indicators of success, when it is known that collection tonnages vary from month to month, in part because there may be different numbers of operational weeks per month. This is why, internally, DSNY uses a tons-per-day metric for operations management. They claimed a reduction of collection costs to one-third of the prior program in an “annualized cost per district” measure, when reporting on DSNY collection costs is presented on per-ton basis in all other internal and external reporting, including in the annual Mayor’s Management Report.

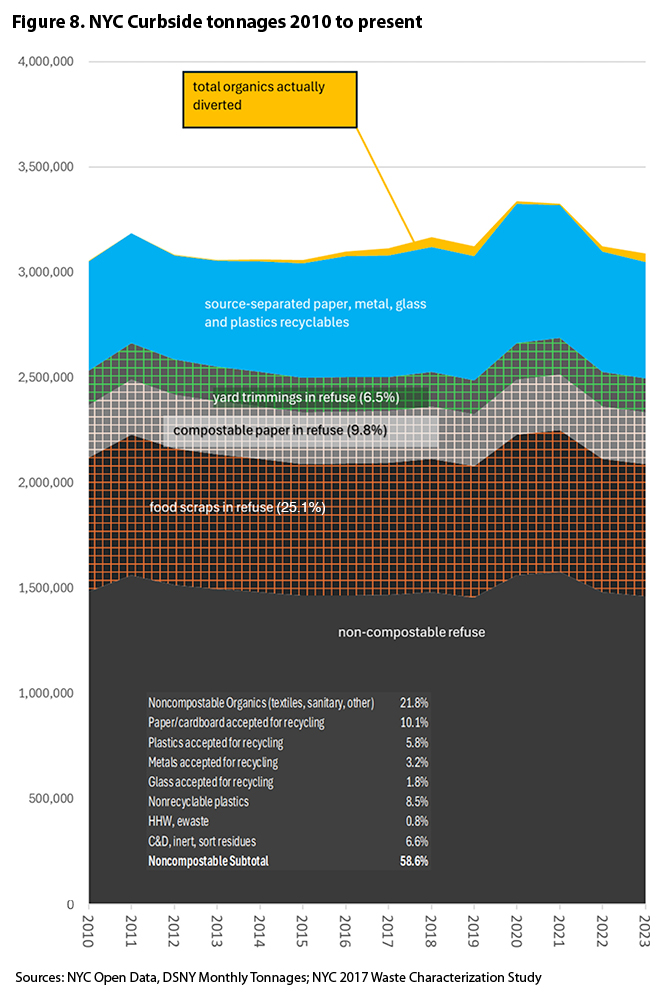

There was no mention of the scale of organics diversion in DSNY’s early reports on program success (DSNY, 2022). Bear in mind that in Queens alone, an estimated 300,000 tons of compostable organics went out with the trash in 2023, headed to landfills and waste-to-energy (WTE) facilities in the eastern U.S. states. From NYC as a whole, the total is over one million tons of trashed, compostable organics. Long-term data on tonnages show the underachievement of organics programs to date in stark relief. Figure 8 shows the quantities of curbside collections going to refuse and curbside recycling, as compared to a small sliver of diverted organics. Over 40% of that refuse citywide consists of compostable organics. The scale of environmentally, economically and socially significant wasting going on is overwhelming.

Elected officials, budget agencies, and state regulators charged with agency oversight need to frame the questions they ask of city agencies more specifically. In addition to requesting refuse totals and per household rates, it is important to track de-aggregated tonnages (not mixing, for example, Smart Bin and school tonnages, or food rescue donations with organics diversion). Those charged with oversight should be asking for longitudinal statistics at the district level, asking how current, seasonal performance of districts compares to those same districts and seasons in years past. Performance should be measured in total tons, monthly per household pounds, and capture rates. Rates should be specific to residential curbside collections, drop offs, and schools, and should be presented at the district level, with transparent calculation methodology and as downloadable datasets, not password protected PDFs.

Some of these metrics are derivable either from Open Data that is already posted, or from statistics that exist internally in some form and would take modest effort to compile for regular reporting. I calculated the capture rates reported here from monthly curbside collection tons, the results of DSNY’s 2017 waste characterization study, and U.S. Census American Community Survey data — all public datasets. In the past, few outside individuals possessed the knowledge to make these calculations, but this is changing. Open Data programs all over the country supply the public with basic operational statistics. Freedom of Information laws mean that citizens can demand additional datasets and reports — if they are aware of their existence. Knowing real achievements, in tons and dollars spent, needs to come to the surface to transparently evaluate — and hopefully improve — program success.

The Problem with Optimism

For over a decade, NYC has celebrated running the largest curbside organics program in the country, while quietly diverting only miniscule tonnages of organics. The gap between success claims and measured results was seen under the previous Mayoral Administration and its aspirational “0 X 30” campaign that aimed at zero waste by 2030. It is seen today, as the City’s “Get Stuff Done” website tells audiences that “NYC is rolling out the nation’s largest compost collection program in Spring 2023. Building on the success of the Queens pilot program launched in Fall of 2022, the curbside composting program will now expand to all five boroughs. Service will be automatic, guaranteed, free and year-round” (City of New York, 2024). Citing stats related to the big size of NYC — like numbers of people or households served, and related aspirations — obscures the far smaller scale of real-world progress.

The endurance of low organics diversion over the past 10 years raises some uncomfortable questions about data and transparency: Should sanitation departments and city sustainability offices openly discuss low diversion or capture rates, high contamination rates, untenable collection costs, or huge landfilled tonnages of GHG-generating refuse? Or should they keep bad news in the background as they struggle to improve? The concern is often that being transparent prevents progress because it is not optimistic. Being forthright may discourage people from participation, the thinking goes. Disclosure may lead to lost opportunities for future federal, state, or municipal funding, or the premature cancellation of programs that need time, and testing, to get going. There is also a political aspect to this dilemma, as cities and their elected officials seek to position themselves as leaders in sustainability, as case studies for other cities to learn from, and as beacons of hope in an increasingly crisis-filled world.

In my experience, when leadership becomes aware of lackluster performance, the choice has been to underplay the bad news. This is not to say that there has been any false information disseminated. Let me be clear: there has not. But members of the public, and even elected officials, understandably lack the experience with waste statistics needed to scrutinize program performance. It is not hard in such conditions to gloss over unruly facts. From the perspective of agency leadership, nothing is gained from statistically informed openness, especially when the complexities of waste metrics, markets, permitting, legislation, regulation, land use, etc. mean that neither the message nor the solution will be simple.

But keeping unruly facts out of the media for as long as possible, which is what has unfortunately happened in NYC over the last decade, sacrifices the efficiency and responsibility that comes with close, responsive attention to empirical data. It is unwise to selectively employ performance metrics as heralds of achievement, rather than operational feedback from which to learn. There is also an ethical aspect to openness. Willingly sharing indicators like capture rate, per household generation, and per-ton collection costs is fairer to everyone with a stake in waste management. It makes decisions on everything from truck technology to receptacle choice to contracting options transparent to small businesses, labor unions, real estate managers, community groups, elected officials, budget oversight agencies, and other stakeholders. It is also more scientific, because only through studying variations in these metrics can we actually test whether forms of program design, service levels, information messaging, building-level technical assistance, and field outreach work where it counts — in tonnage and improvements to people’s lives.

Then there is the issue of contamination. Being open requires sharing up to date waste characterization data not only for refuse, but for source separated organics. If those organics are contaminated with plastics or other materials, and there is technology that can decontaminate them, then by all means report residue removal rates and the fate of those residues. Make results of ongoing testing of finished compost public directly, as opposed to buried in state reporting. Be up front about regulated pollutant levels as well as the presence of emerging contaminants of concern like microplastics and forever chemicals that states may not yet require municipalities to test for.

On a programmatic level, the case of Queens demonstrates that a dynamic response to findings on capture and per household generation rates is needed because there are neighborhood differences in the built environment. People live and work in the built environment, and being continually responsive to how they think zero waste programs should work in their homes and workplaces has to be part of the ongoing development of those programs. Facing the special challenges in multi-unit buildings, and the seasonal, locational quantities of yard trimmings, may lead to a reconsideration of whether co-collection of these streams makes the most sense, or if seasonal yard trimmings collection and more frequent service routes in very dense areas are needed. It’s not going to be simple, I’m sorry to say, but these steps build the foundation for program success.

Seeking community input has to be ongoing, with two-way communication, for it to be meaningful and not pro-forma. Such approaches may be out of the norm in many cities today, but the world is changing. More and more, as seen with the achievements of the climate action and environmental justice movements, people are not standing for lack of real action in the face of environmental, social, and economic crises. Tough questions won’t go away. If anything, as seen in the work of NYC’s community composting and allied movements, tough questions are getting more sophisticated and urgent.

Without open discussion of the bad as well as the good, we run the risk of repeating past mistakes. Even worse, putting the most positive spin on performance can lead to kicking the can down the road for another administration, or future generations to resolve. This is perhaps the most important lesson I have learned as a New Yorker inside, and outside, waste management governance. It motivates my own assessment of NYC’s Curbside Organics Collection Program because I want this program to succeed. It motivates these recommendations, as challenging as I know they are for large bureaucracies, because I don’t think NYC can continue to pursue real and just sustainability without them.

At the moment, policy options for outreach, education, enforcement, program design, collection arrangements, and alternatives cannot really be contemplated without facing some hard facts. New York City’s aim to be the biggest municipal organics program in the nation can succeed, but its approach to waste governance must radically change.

Samantha MacBride, PhD, teaches urban environmentalism, public management and program evaluation at Baruch College’s Marxe School of Public and International Affairs, and worked on the New York City Department of Sanitation’s curbside recycling and organics programs for over two decades. She retired from the New York City Department of Environmental Protection’s Bureau of Wastewater Treatment, where she managed process engineering research, development and training. She is currently pro bono Advisor to Earth Matter, a leading organization in community composting.