Nancy Deming and Janet Whited

The image of served but not consumed school food in a dumpster can be used to illustrate the opportunities presented by a K-12 reduction and recovery program. Photo by Nancy Deming

The Oakland Unified School District (USD) in northern California, and the San Diego USD in southern California, recognize the high value of the surplus food resource inherent in school meal programs and the influence of that value to guide wasted food reduction and using surplus food to help feed the community while keeping good food out of landfills. A variety of surplus food reduction and recovery initiatives have been implemented at Oakland USD and San Diego USD, including food share tables and food donation programs.

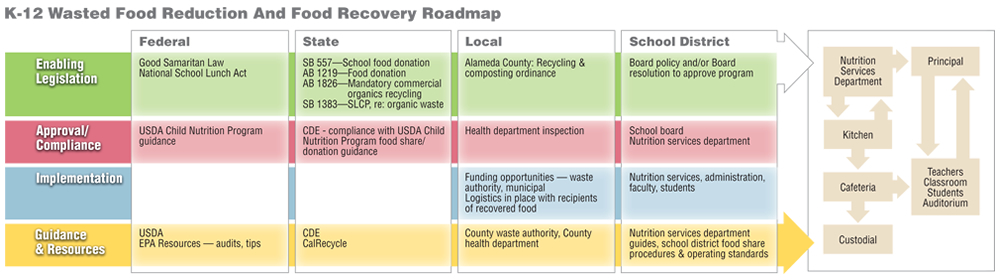

Starting these types of programs can seem daunting at first, since there are a number of steps to consider before initiating surplus food reduction and recovery programs. Don’t be discouraged! This article is a guide to the steps and initiatives taken at Oakland USD and San Diego USD to reduce and recover school meal leftovers. It focuses on best practices and includes a customized roadmap (see flow chart) on how to save surplus food at school, as well as resources for school waste reduction and sorting. New California mandates and legislation can be a catalyst for school meal recovery and may be referenced for assistance and support — as well as replication in other states, localities and school districts.

Roadmap

The K-12 Wasted Food Reduction and Food Recovery Roadmap is designed as a flow chart and can be customized for a state, local region, and school district. There are three primary levels to create food waste reduction and food recovery programs: Enabling Legislation; Approval/Compliance; and Implementation. All of the steps are informed and assisted by Guidance & Resources, the fourth level in the Roadmap.

There are four primary “entities” in a food waste reduction and recovery program — Federal, State and Local Governments, and the School District. Using the Approval level as an example, Local Government and the School District are the entities that generally issue Approvals. The School District is the primary interface between the Nutrition Services Department (i.e. food services provided to schools) and the administrators at the schools. Once a food share program is implemented in a school, the primary interface between the food services provided and faculty/students, shifts to the cafeteria. A secondary interface is between the school kitchen and cafeteria in determining the re-serving potential of items remaining on food share tables.

The color-coded boxes correspond, color-wise, to their activity on the Roadmap. Information in the color-coded boxes will assist all stakeholders in K-12 wasted food reduction and food recovery program implementation.

Engaging Stakeholders

Informing decision makers on the laws and regulations surrounding food donation, share tables, food waste, and landfill diversion requirements helps make the case for investigating surplus food reduction and recovery options at the school district level. Many regulations are supportive of these initiatives specifically, while others are restrictive, i.e., providing strict parameters and guidance on acceptable practices.

Identifying key stakeholders, especially the Nutrition Services Director, is paramount. The majority of all food recovery initiatives need to be vetted through the school districts’ Nutrition Services Department to address any high level areas of concern, including capacity to accomplish the program’s goals and priorities. Consider incorporating food waste reduction as part of the scope of the overall program to minimize the amount of leftover food that must be managed. Just getting the conversation started and reviewing options with staff along the way helps increase focus and awareness on wasted food and keeps the program moving forward.

As a best practice, review and discuss plans and documents with a few nutrition services department staff and school site kitchen managers for feedback. Piloting is advised to work out details and make adjustments before a project expands districtwide. Approvals to implement food share programs may be needed from the district’s school board and the local health department. One option for the school board is to adopt a “saving food resolution” that provides both board approval and support for the program. With the health department, review food share and food donation procedures, as well as the process and details for re-serving items remaining on food share tables, to obtain their feedback and approval. Once all approvals and program customization are in place, food share and donation programs can typically be finalized and implemented by nutrition services staff.

Ten key steps (and “substeps”) to creation of K-12 school food recovery programs, such as food share, are described in the “Action Steps” sidebar.

Food share table and 3-bin sorting station at school in the Oakland Unified School District. Photos by Nancy Deming

Funding

Many of these initiatives cost very little to implement. Internal costs to the District/Nutrition Services Department can include the procedural step of adding food share item counts and reasons for the leftovers to the Menu Production Worksheets (kitchen forms that log all required serving details for each meal); food share table set up procedures; staff training, including development of training materials; and any development or printing of signage, banners, or other program education and outreach items. Additional funding will most likely be needed for “infrastructure,” including any needed cafeteria and kitchen improvements, additional refrigeration, and transport logistics for a food donation program.

Investigate local, regional and national funding that may be available. In California, for example, CalRecycle recently funded a grant program specifically for food recovery implementation. A local waste authority may have suggestions and/or support. For example, Alameda County’s waste authority, StopWaste, provides support to deal with school food waste issues with its “Food Too Good To Waste” student action projects and grant funding. Oakland USD was able to tap into these resources and received a $25,000 food reduction and recovery grant to help jump-start its program. Publicizing the program and outreach to the wider community may attract financial support. Many waste haulers are becoming more involved in food waste recovery and may offer support. Local food banks and hunger relief organizations may also be able to assist.

Nancy Deming is a K-12 Sustainability Specialist who works with Custodial and Nutrition Services at the Oakland Unified School District, the Central Contra Costa Solid Waste Authority’s Recycle Smart Schools Program, and Alameda County Schools and District. Janet Whited is Interim Energy/Utilities Program Coordinator, Operations Division, at the San Diego Unified School District.