Paul Greene

Wastewater treatment plants with anaerobic digesters, such as the City of Gresham, Oregon, have installed capacity to receive high strength organics for codigestion. Photo courtesy of City of Gresham

Full-scale commercial anaerobic digestion facilities operating as merchant plants receive outside solid and liquid feedstocks both for their tipping fee revenue and their biogas yield potential. And increasingly, wastewater treatment plants with anaerobic digesters are building capacity to receive high strength organics for codigestion.

Feedstock receiving infrastructure that is as operator friendly and odor-free as possible is critically important to the long-term success of these digesters. Logistical decisions related to designing, sizing, installing and operating a proper receiving station for such digester facilities are discussed in this article. These decisions need to factor in variations in climate and ambient conditions.

Feedstock Flow Path

Along the flow path to the digester are many steps that include tipping pits, screening, pumping, storage, hydrolysis and flow equalization. The following considerations need to be taken into account when designing a receiving system:

Many transporters’ trucks deploy gravity offloading and thereby will tip into in-ground pits (above) or covered tanks and vaults.

Tipping Pits. Many transporters’ trucks deploy gravity offloading and thereby will tip into in-ground pits or covered tanks and vaults. Haulers need the ability to rapidly dump whatever contents are in the truck to have quick turnaround. Some loads, such as grease trap wastes, can have rocks and rags and other trash in the waste that need to be managed. All practical measures should be taken to settle out rocks, grit and metals ahead of the digester with devices such as a rock trap, which the wastewater treatment industry has used well for decades. Rags and other debris can be ground to smaller particles through grinding pumps.

Above Grade Tanks. Some haulers have pressurized trucks that can push material into above grade tanks. Screening this material can be more challenging as it is all enclosed in a pipe on its way into the holding tank. Some facilities are set up with multiple above ground tanks that can handle more dilute or more concentrated material. Haulers with gravity draining trucks can tip into a small pit where a higher speed pump can be deployed to fill a tall above grade tank.

Receiving Tank Sizing. During project design a developer might assume the facility will be receiving, for example, 6 to 10 trucks/day of liquid waste. At 5,000 gallons/truck, that equates to 30,000 to 50,000 gallons of material daily. Receiving tanks should be sized to handle at least a day or two worth of material in order to continue serving feedstock clients’ tipping needs if downstream equipment such as a feed pump is being repaired or if the digester is in a process upset. Some digesters will include a number of feed tanks to be able to adjust the digester feed recipe based on waste composition and strength.

Screening Systems. Manually cleaned bar racks are common — and a common headache. They can be prone to freezing in winter, and are a potential odor source. Nonetheless, bar racks allow for ease of maintenance and efficiency, while being low cost. Vendor packages, like the JWC Honey Monster, provide proper screening and grinding of this material based on its use for septage receiving. Rock traps, again, are useful for settling out the occasional metal part that can be found in off-site wastes.

Conveyance. With in-ground style tanks, submersible chopper pumps are common for conveying material to the digesters. They function while completely submerged in water, help with particle size reduction and move material efficiently to downstream processing. In above ground tanks, progressive cavity and rotary lobe pumps are common for moving materials to downstream processing. In all cases, feedstock contamination can be a big issue if there are quantities of undesirables like rocks, rags and metals. One operating trick CDM Smith has deployed at wastewater treatment codigestion facilities — and which can be deployed at merchant digesters — is to recirculate hot digested sludge through feed lines to keep them clean.

Feed Tank Mixing. Submersible style and jet mixing systems are common to keep material circulating and to keep debris and grit from accumulating in tank corners. Material for these components should be selected for long term duty — such as stainless steel or fiberglass — due to the corrosive environment and the amount of feed contamination.

An induced draft fan can pull odorous air out of the head space over a tipping tank and send it to an odor treatment system such as a biofilter (above).

Tank Odors. When new feedstock is introduced into a holding tank, all of the odorous air in the tank is purged, which can be very problematic if it isn’t captured and treated. Fixed roofs on storage and tipping tanks are recommended. These roofs allow operators access and can contain the gases that come from odorous feedstocks. The head space over a tipping tank should have negative pressure pulled on it. An induced draft fan can pull the odorous air out and send it to an odor treatment system such as a biofilter or carbon filter. In the case of a large facility, a chemical scrubber or thermal oxidizer can be used to scrub or burn the odor-causing compounds that come from feed tanks.

Tank Temperature and Heating. In colder climates, some heat may be required to keep feed tank contents from freezing during weekends and downtime. Heat is commonly introduced through a black iron or stainless steel pipe mounted to the tank floor and/or walls. Tank heating beyond simple freeze control is not recommended as elevating the feedstock temperature can cause material to biodegrade and become odorous. Digesters with a typical 30-day residence time should be able to warm up cold feed once it is in the digester and not experience an impact on performance.

Heating digester feed can also lead to mineral build up in the feed piping. Overall, line plugging can be addressed by not storing feedstocks for longer than 24 hours and using glass lined ductile iron piping and line velocities in the 3 to 5 feet/second range in all the feed piping.

Flow Equalization. Digesters like to have a constant feed rate and strength in order to keep its biomass stable. Strength is commonly measured as COD (Chemical Oxygen Demand). The COD test is an oxidative test that determines the overall quantity of organic matter in a waste. Each incoming load should ideally be checked for its COD content. Because the digester is going to commonly receive material with COD concentrations anywhere from 50 to 1,000 grams/liter, it is prudent to either adjust the feed rate to accommodate for COD variance or to provide a day’s worth of flow equalization — basically 24 hours of storage with the contents completely mixed prior to digester feeding. This essentially dampens swings in feed COD.

Process Chemistry

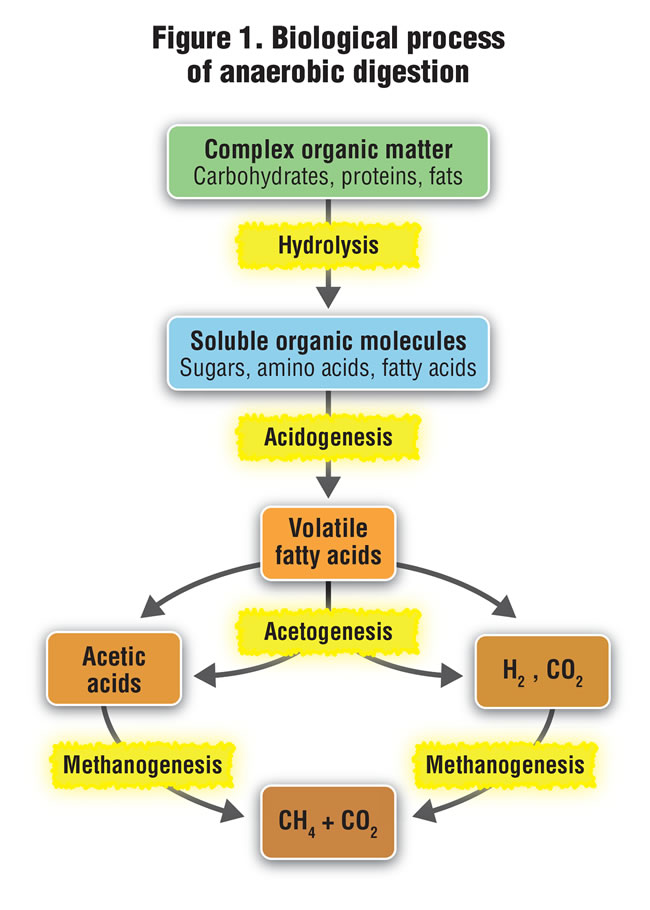

Anaerobic digestion is a four step biological process (Figure 1). Organic waste undergoes hydrolysis and acidification (known as acidogenesis) steps, where large molecules are broken apart and organic acids are formed in a relatively quick reaction. Material at this phase has a foul odor and can be considered “rancid.” If material is kept in the feed storage tank for an unduly long amount of time or at an elevated temperature, these biological reactions can start and be quite odorous.

For example, fermentation bacteria can take hold in a storage tank and generate CO2, hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and vinegar-like acid compounds and can be prone to foaming events from the dissolved gases. The pH coming out of a storage tank that’s actively fermenting can be very low — commonly <3 due to acid formation. Facilities that choose to heat the incoming feed tanks to raise content temperature take the risk of the fermentation process rapidly taking hold, leading to possible odor complaints due to vent gas releases if there is no containment and treatment in place.

Aeration, Enclosed Tipping

Everything in nature exists in either an oxidative or reducing state. In the part of nature where oxygen is abundant, known as an aerobic environment, all things are being oxidized while in an oxidative state. In settings where oxygen is not present, a reducing environment is found. Bacteria found in these settings feed off molecules like sulfate where sulfur-reducing bacteria, for example, generate H2S gas. (Think of the bottom of a gym bag containing work out clothing, where oxygen isn’t present.)

At digester facilities, it is always considered to be a healthier scenario when holding tanks are aerated. Material kept in a positive dissolved oxygen setting will smell fresher and avoid entering a reducing state.

Finally, it is common for offloading of feedstocks to occur outdoors, with the fugitive odors creating a possible issue with neighbors. Digester facilities receiving high strength feedstocks may want to consider using enclosed receiving stations equipped with odor control. Incoming trucks can pull in and unload. A less expensive option is to build a receiving station that just partially encloses the back end of the truck while tipping.

Properly designed receiving and storage tanks are of paramount importance to the ongoing commercial success of digester operations. End users should give great thought and planning to the potential that both fugitive and vent stack odor emissions can have on long-term facility success.

Paul Greene is the AD and Biogas Practice Leader for the Private Sector division of CDM Smith, a leading designer and builder of digestion and gas upgrading infrastructure. He can be reached at (518) 951-5766 or greenep@cdmsmith.com. He is also Co-Vice Chairman of the American Biogas Council.