Overall, demand for RNG is strong in spite of an oversupply of D3 RINs in 2018.

Nora Goldstein

BioCycle September/October 2019

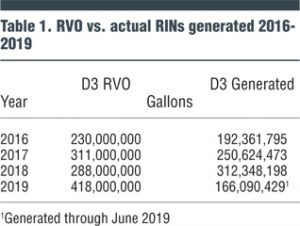

In 2018, cellulosic biofuel producers, including those making renewable natural gas (RNG), outperformed the annual Renewable Volume Obligation (RVO) quantity for D3 RINs (Renewable Identification Numbers) set by the U.S. EPA under the federal Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS). This was a first in the RNG industry since 2014, when cellulosic biofuels qualified for cellulosic RINs, says Brad Pleima, Senior Engineer at EcoEngineers, who leads EcoEngineers’ renewable natural gas line of business. “The RVO was set at 288 million gallons, and 316 million D3 gallons were produced,” he explains.

Pleima authored an excellent article, “Biogas To RNG Projects: What, Why And How,” in BioCycle that explains all the fundamentals related to RFS, RVOs and RINs. Here are a couple of highlights, which will help to understand current market conditions for cellulosic fuels generated by biogas facilities:

RVO: The actual, total volume of renewable fuels that must be blended into the transportation sector during a given year. Since the inception of the RFS, the available supply of cellulosic renewable fuels has been significantly lower than the volumes proposed by Congress in 2007, causing the U.S. EPA to set an alternate RVO each year (see Table 1).

RINs: Each gallon of renewable fuel under the RFS is able to generate credits or RINs. The RINs are the currency of the RFS and are used by obligated parties as a compliance mechanism to meet the annual RVO mandate.

Obligated Parties: Petroleum refiners and importers of refined fuel into the U.S. are the obligated parties. They can obtain RINs by producing renewable fuels that qualify for RINs, purchasing renewable fuels with RINs attached, or purchasing RINs that have been separated from renewable fuels.

D3 and D5 RINs: Biogas to RNG falls into the D5 or D3 RIN categories depending on the feedstock processed. RNG produced from cellulosic feedstocks can generate D3 RINs while non-cellulosic feedstocks like fats, oils, sugars, starches, and most food wastes, can generate D5 RINs. Historically, high demand exists for cellulosic biofuels and D3 RINs due to supply constraints.

Cellulosic Waiver Credits (CWC): Recognizing short-term difficulty in attaining required volumes of cellulosic fuel, EPA offers CWCs at a price determined by formula in the statute. Obligated parties have the option of purchasing CWCs plus an advanced RIN (D4 or D5) in lieu of blending cellulosic or obtaining a cellulosic RIN.

CSREs: Small Refinery Exemptions are temporary exemptions granted to small refineries from their annual Renewable Volume Obligations (RVOs) if they can demonstrate that compliance with the RVOs would cause the refinery to suffer disproportionate economic hardship.

In his presentation at BioCycle REFOR19, Pleima will provide an update to changes and market conditions for the RFS and California and Oregon’s low carbon fuel programs. BioCycle interviewed Pleima (August 2019) to get a sneak preview.

BioCycle: How would you characterize the RIN market in late August 2019?

Pleima: The oversupply of D3 RINs in 2018, combined with the Small Refinery Exemptions issued by EPA, have driven D3 RIN prices down this year — from above $2.00/RIN in 2018 to $0.60/RIN as of August 2019. The question for the rest of 2019 is: Will the oversupply happen again? Right now, obligated parties are waiting to buy RINs to see what happens in the market, although the RINS must be purchased by the end of the year. At the same time, some RNG producers are sitting on their RINs with hopes that the price per RIN will increase before year-end.

BioCycle: How do the CWCs and SREs impact this “wait and see” game?

Pleima: In the past when the industry did not produce enough D3 RINs to meet the annual RVO, obligated parties have purchased Cellulosic Wavier Credits (CWC) plus advanced RINs to satisfy the D3 obligation. But in 2018, there was an oversupply of D3 RINs compared to the RVO, which depressed prices. And the SREs issued by EPA has waived upwards of 10 percent of the overall RVO obligation, further worsening the oversupply issue.

As for SREs, EPA has issued these exemptions each year but the number and overall RINs exempted have increased dramatically recently. In 2013, for example, it waived 190 million RINs. For calendar year 2017, that rose to 1.8 billion RINs, and EPA announced in August that it granted 31 small refinery exemptions for the 2018 compliance year (6 were denied) that total 1.43 billion gallons. In short, the foundation of the RFS program is there by statute, but politics enter into how the annual RVO is set, and with SREs, how much of that the obligated parties will be held to. This ends up impacting D3 RIN prices.

The public comment period for EPA’s proposed rule to set 2020 RVOs under the RFS closed at the end of August. The rule proposes to require 20.04 billion gallons of renewable fuels to be blended with the U.S. fuel supply next year. Cellulosic biofuel comprises about 540 million gallons of that proposed volume. The RNG Coalition requested that EPA set the cellulosic biofuel volume at 650 million gallons for 2020 to include expected production, as well as to account for potential year-to-year carryover gallons of biofuel and SREs that may be granted by EPA. If some of that expected production is in projects being developed or constructed, and they are looking at $0.60/RIN, the developers may actually pause the project. We are seeing this with some landfill RNG projects, especially because those carbon credits are of lesser value [than biogas from anaerobic digestion facilities] in state programs such as California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard’s (LCFS) market.

BioCycle: Can you explain how the year-to-year carryover gallon allowance impacts D3 RIN prices as well?

Pleima: Up to 20 percent of an Obligated Party’s annual compliance can be fulfilled by using RINs purchased in the previous year. In other words, if an Obligated Party has a 10 million D3 RIN obligation for 2019, up to 2 million of those RINs can be RINs generated in 2018. This impacts current RIN pricing, depending on how many previous year RINs each Obligated Party uses.

BioCycle: What are some bright spots on the horizon?

Pleima: California’s LCFS is booming and strong, and most projections are that the LCFS credit pricing will remain strong. Oregon’s Clean Fuel Program is starting to take off as well, with current prices in the $150/credit range, up from the $20s and $30s per credit. Washington State is trying to establish an LCFS program, and there is discussion about one starting in several other states.

The other bright spot is demand for RNG by companies with a corporate social responsibility mandate such as Apple, Google, Facebook and L’Oreal. And several natural gas utilities are purchasing RNG under what they call a green tariff. We are seeing a lot more of this voluntary market development. It is actually competing for RNG with RINs and LCFS credits because the private companies and utilities don’t need to pay as much to procure them. These long-term agreements — some contracts to purchase RNG are 10 years and up to 25 years — are not directly impacted by government uncertainty.

The takeaway for now — and what I’ll discuss at BioCycle REFOR19 — is that while RIN prices are up and down, the foundation of the RFS program is a law that has to be enacted. There is demand for RNG over the long term. There has just been more volatility on RIN pricing this year. But the overall trends within the RNG industry are very strong.