Installation of food waste depackaging facilities across the state results in fewer commercial organics ban exemptions for packaged food generators.

Robert Spencer and Morgan Casella

BioCycle January 2018

Off-spec packaged foods include out-of-date, mislabeled, damaged, and spoiled products. Photo by Robert SpencerFood waste disposal bans are on the books in Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Vermont, and under consideration in New York and other states in their quest for solid waste diversion rates of 50 percent or higher. The common denominator in those four states is that generators of 1 ton/week of food waste are subject to the bans, as follows.

• Connecticut: Institutional-Commercial-Industrial (ICI) generators of 2 tons/week (1 ton/week effective in 2020)

• Massachusetts: ICI generators that dispose of 1 ton/week

• Rhode Island: ICI generators of 2 tons/week (1 ton/week effective in 2018)

• Vermont: Phased in starting July 2014 with 2 tons/week from all generators, and now one-third ton/week (expands to all residential generators by 2020)

A two-part article last fall in BioCycle by Carol Adaire Jones of the Environmental Law Institute (“Organics Disposal Bans And Processing Infrastructure,” September 2017, and “Food Waste Infrastructure In Disposal Ban States,” Nov. 2017) explains these bans in detail. State solid waste management officials promote food waste diversion as a way to save money on solid waste disposal costs, or at least break even. Cost savings may or may not result from separate collection of organics.

Processing packaged and containerized food waste that must be diverted under these bans to composting or anaerobic digestion facilities is difficult, since the packaging must be removed. Off-spec packaged food results from out-of-date, mislabeled, damaged, and spoiled products, and can comprise a significant portion of a manufacturer’s waste volume even after food is salvaged for food banks and animal feed. But increasingly, machines are being installed that tear apart and separate the packaging, e.g., yogurt containers, cereal boxes, plastic bags of frozen blueberries, and shrink-wrapped meat and vegetables. This game changing technology is now creating outlets for packaged organic materials to be recycled, and in some cases, the packaging as well.

But depackaging equipment is expensive, on the order of $250,000 to $500,000 for the separator equipment alone. Another couple hundred thousand dollars are needed for ancillary infrastructure such as a building, receiving area, and liquid storage tanks.

Technology Investments In Massachusetts

Recognizing that it would take considerable time, and investment, to establish the infrastructure to depackage food waste after its food waste disposal ban went into effect in October 2014, the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) created the following guidance regarding commercial organic materials from businesses, institutions, and haulers:

The food waste depackaging trial at E.L. Harvey & Sons’ facility processed 27.6 tons of packaged food waste. Material was loaded into an auger (1) that feeds the Scott Turbo Separator (2). Separated packaging (3) had to be disposed. The food waste slurry (4) was transported to anaerobic digesters. Photos by Robert Spencer

“Whenever possible, food waste should be removed from packaging at the point of generation, or be sent to a facility that can remove the packaging from the product. In cases where this is difficult and technology or facilities are not available to remove packaging from the product, then the generator can apply for an exemption from the waste ban for that material.”

Since the state food waste ban took effect, MassDEP has granted a number of exemptions for food processors or distributors who commonly dispose of off-spec packaged food products. Over the past 2 years, however, five depackaging systems have been installed in Massachusetts, primarily by waste haulers. One of the first haulers to invest was E.L Harvey & Sons, in Westborough, Massachusetts (see “Depackaging At Solid Waste Transfer Station,” May 2017). A Scott Turbo Separator was installed in fall 2016 in an enclosed area next to Harvey’s trash transfer station. Other depackaging facilities in Massachusetts include:

• Waste Management Boston CORe, Charlestown

• Troiano Trucking, Grafton

• Parallel Products, New Bedford

• Recycleworks, East Weymouth

• Stop & Shop, Freetown (processes Stop & Shop material for an on-site anaerobic digester)

Commonwealth Resource Management Company (CMRC) in New Bedford (MA), which operates a food

waste anaerobic digester at the Crapo Hill landfill, is also installing depackaging equipment. It currently processes liquid food waste, but will expand to solid food waste once the systemis installed.

There are also two anaerobic digestion facilities in neighboring states with depackaging technology that currently receive food waste from Massachusetts food waste generators. These include Exeter Agri-Energy in Exeter, Maine (see “Regional Digester Increases Food Scraps Processing,” November 2016) and Quantum BioPower in Southington, Connecticut (see “Merchant Biogas Plant Services Food Waste Generators,” July 2017).

To facilitate increased food waste recycling infrastructure, the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) awarded several Recycling Business Development Grants to companies to subsidize the cost of the depackaging systems:

• E. L. Harvey received $100,000 to construct a liquid storage tank for depackaged, liquefied food waste.

• CRMC received a $200,000 grant to purchase depackaging equipment that will enable the facility to accept and process bulk organics that are packaged or have some level of contamination into pumpable slurry for anaerobic digestion.

• Troiano Trucking received a $200,000 grant to purchase depackaging equipment that will enable the facility to accept and process bulk organics that are packaged or have some level of contamination, for use in animal feed.

Ban Enforcement

Ben Harvey, Vice President of E.L. Harvey & Sons, has been working with MassDEP to demonstrate the viability of the Scott Turbo Separator system that he and his cousin Steve Harvey have been intimately involved with as a new business venture. Most of the depackaged food from E.L. Harvey’s transfer station is converted into liquid slurry and transported to anaerobic digesters in Massachusetts and Maine. One of the challenges for E. L. Harvey has been receiving enough packaged food waste to offset the cost of the depackaging facility, estimated at over $600,000.

“As a private business that made this investment, we appreciate MassDEP’s enforcement of the food waste ban for packaged food, and we expect existing exemptions will not be renewed,” explains Ben Harvey. He acknowledges that MassDEP has been consistent in not granting exemptions to “one-off” disposal requests, e.g., where there is one load of spoiled material that would have traditionally gone to disposal, but “we need to have fewer exemptions for food manufacturers who consistently have loads that could be recycled at our facility, or other facilities.”

With at least six commercial depackaging facilities in operation in the New England region, MassDEP acknowledges it is issuing packaged food waste ban waivers less frequently and instead referring companies to depackaging facilities. MassDEP is also stepping up enforcement of the ban, including notices of noncompliance (NON) to 15 generators, and a financial penalty to one company upon its second violation.

According to MassDEP’s John Fischer, Branch Chief of Commercial Waste Reduction, waste ban violation fines can range from $860 to $1,000 per offense. Fischer explains that MassDEP employees conduct inspections at transfer stations, landfills, and waste-to-energy facilities. Inspectors are trained to visually inspect loads as they are dumped on the tipping floor, and estimate if there is one ton or more of food waste in the load. Acknowledging that it can be difficult to estimate how much food waste is in a load, Fischer says that inspectors take photos from several perspectives, get copies of the load scale ticket to obtain the weight of the load, and then review and discuss the load documentation internally following the inspection.

If the waste is collected in a dedicated compactor or roll-off container, it is easy to identify the source. But in cases of multiple generators’ materials in a load, some “dumpster diving” is required to identify the name or address of a generator.

Separator Demonstration

Just north of the Massachusetts’ state line in Brattleboro, Vermont, Dynamic Organics, LLC operates a landfill gas electric generating facility in accordance with a lease from Windham Solid Waste Management District (WSWMD). That facility has a 300 kW combined heat and power (CHP) generator, but only 100 kW of electrical generation is currently produced due to declining methane gas from a 25-acre landfill that was closed and capped more than 20 years ago.

Dynamic Organics has partnered with Sky Solar Holdings LLC, which is constructing a 5 MW solar array on the landfill, to conduct a feasibility study to assess the installation of a food waste digester to supplement the dwindling landfill methane. With funding from a Vermont Clean Energy Development Grant through the Windham Regional Commission, the feasibility study included a demonstration at E.L. Harvey’s depackaging facility in July 2017. Given the number of large supermarket chains and food distribution companies operating in the region, there is potential to develop a depackaging facility at the Brattleboro WSWMD site to serve generators from Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont.

Such a depackaging facility would be integrated with WSWMD’s existing food waste aerobic composting facility at its site in Brattleboro, just a mile off Interstate 91. The WSWMD would host the facility and lease the land to Sky Solar Holdings.

Other project drivers include the existing 300 kW generator and electrical grid interconnection, as well as a recently acquired Vermont Standard Offer feed-in-tariff of 20.8 cents/kWh of electricity produced from food waste biogas. The depackaging facility could be installed in an existing 7,500 sq. ft. building adjacent to the Sky Solar landfill gas to energy facility.

The purpose of the separator demonstration was to document the percentage of packaged food that could be recovered by E.L. Harvey’s Scott Turbo Separator, Model T42. Two tractor-trailer loads of packaged food waste were delivered to the facility for the trial. The separator has capacity to process 18 to 20 tons/hour, but during the trial was operated at a much lower rate since there was a wide range of packaged material, including frozen foods, and perishable materials. The frozen foods were delivered 24 hours ahead of the trial to allow them to thaw in the July heat since solid frozen materials cannot be processed in the separator. Project participants paid E. L. Harvey’s tip fee of $125/ton to process approximately 28 tons of packaged food over a 6-hour period.

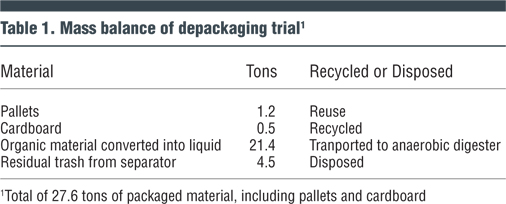

Table 1 provides the mass balance of the depackaging trial, and recycling outlets for recovered materials. Of the 27.6 tons processed, the residual waste requiring disposal was 16 percent.

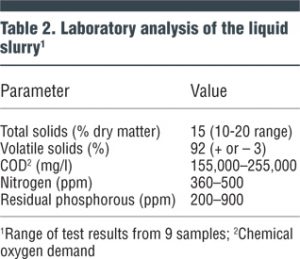

To determine the biogas potential of the liquid slurry, 9 samples were collected and sent for laboratory testing (results in Table 2). Based on the volatile solids and COD results, the slurry had good biogas potential, and was successfully processed at an AD facility.

The project also looked at potential labor savings from a food distribution warehouse where 11 employees are dedicated to manually opening and sorting packaged food waste products, which are then hauled to a composting facility. Conservatively, the company estimates that 3 employees could be reduced in the recycling department and work elsewhere in the warehouse, with the associated food waste recycling labor costs reduced.

Next Steps

The AD facility developers are evaluating a number of technologies, primarily liquid systems. Total capital costs are estimated at $1.5 million to $2.0 million for a facility that would process 10,000 tons/year of food waste, generating 300 kW of electricity. The project is able to save significant costs by utilizing the existing infrastructure — the CHP generation unit, interconnection, and associated warehouse and concrete pad space.

Preliminary findings show that the proposed AD facility could be integrated with WSWMD’s existing food waste composting facility, even using some portion of the liquid anaerobic digestate in the aerobic composting process. One of the biggest challenges is securing a minimum of 10,000 tons/year of food waste. However, if several anchor contracts can be negotiated with a supermarket chain or food distribution company, the project may be developed.

Dynamic Organics and Sky Solar Holdings are in the process of securing anchor contracts, and depending on the results of further financial analysis, and approval from Windham Solid Waste Management District, could break ground on the depackaging and anaerobic digester facility in 2018. The project would be privately financed by Sky Solar Holdings in a public/private partnership with Dynamic Organics and WSWMD.

Bob Spencer is Executive Director of Windham (VT) Solid Waste Management District, and a Contributing Editor to BioCycle. Morgan Casella is with Dynamic Organics.