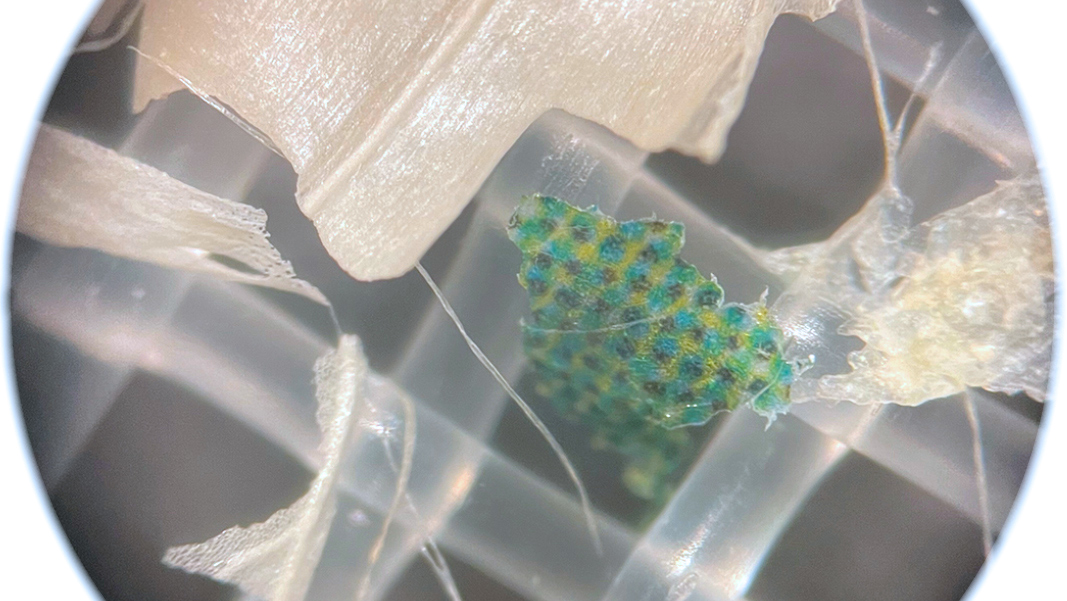

Top: Microplastics under microscope. Photo courtesy Kate Porterfield

Craig Coker

There are no standardized procedures for measuring microplastics (MPs) in composts, digestates, and food wastes. Evaluating MPs requires they be isolated from the substrate being studied and then analyzed to identify them. Isolation methods reported in the literature include flotation, centrifugation, elutriation (a process similar to an air classifier on a compost screener discharge belt), and sieving. Identification methods reported include fluorescent microscopy, thermal degradation, spectroscopy, and visual analysis.

Many analyses report results on a count per weight basis; others report on a weight-to-weight (w/w) basis. There is no consistent way to convert between these two different quantification methods without knowing shape, size, and plastic polymer type. Regulatory limits and ecotoxicity thresholds are usually expressed on a w/w basis. Enforcement of regulatory thresholds defined by w/w units will require advancements in measurement methods. Furthermore, plastic size classes included also vary widely across studies.

Kate Porterfield measuring biochemical methane potential for mechanically depackaged food wastes that were also analyzed for microplastic contamination at the University of Vermont. Photo courtesy of Eric Roy

Research at the Gund Institute for the Environment at the University of Vermont (UVM) is focused on addressing these measurement and analysis issues. A team led by Dr. Eric Roy, Associate Professor at the Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources, and including Kate Porterfield and Sarah Hobson, graduate students working with Roy, has been measuring and characterizing MPs. They started with a comprehensive literature review from research around the world (Porterfield et al., 2023) and have been testing and analyzing food waste, compost, and digestate samples collected in the state of Vermont. “We have been working for two years on methods development to measure MPs in food wastes, digestates and composts,” explained Roy during a November 2022 Vermont Depackager Stakeholder Group meeting. “Not only do standard methods not exist for these material types, but methods for environmental samples, such as water or mineral soils and sediments, have key limitations for samples rich in organic matter.”

Porterfield and Hobson have been testing these materials by first removing the organic matter with hydrogen peroxide, then conducting a visual inspection at a 40x magnifying power. They sort the MPs into three size ranges, 0.5 to 1 millimeter (mm), 1 to 5 mm, and greater than 5 mm. They also sort the MPs by shape (film, fiber, fragment). The MPs are weighed (if possible) to determine masses and then spectroscopy has been used to identify plastic polymer types — comparing results to a polymer library borrowed from a laboratory in Germany. “One thing I’ve noticed in this work on food waste and digestate is that film plastics contribute a lot to the particle counts but much less to the mass measurements,” Porterfield told BioCycle Editor Nora Goldstein in a February 2023 interview. “And while film plastics can be quite abundant, it’s actually plastic fragments that are contributing disproportionately to the MP mass in my samples. A single, relatively large MP fragment could weigh a lot more than many smaller film particles. That one fragment could end up in an analyzed sample and raise the overall MP mass in the sample, perhaps beyond regulatory limits.”

Microplastics In Composts And Digestates

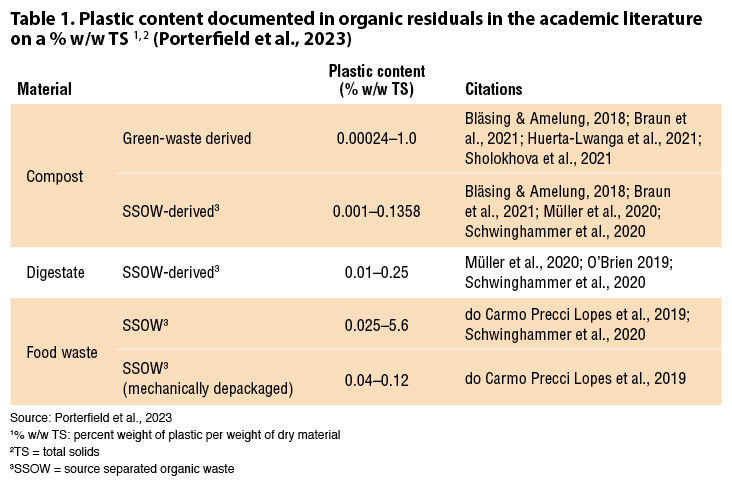

Porterfield et al. (2023) has the most comprehensive list of research into MPs in composts and digestates. The UVM team’s literature review results for plastic content in organic residuals on a percent weight per weight (w/w) total solids (TS) basis (%w/w TS) are shown in Table 1. Much of this research has been focused on plastics larger than 1 mm. Plastic abundance on a particle count basis varies widely for each material, depending on size fractions included, methods, and sample. Results range from 12 to millions of plastic particles per dry kg for compost, 39 to millions of plastic particles per dry kg for digestate, and 36 to 300,000 plastic particles per dry kg for food wastes (Porterfield et al., 2023). It is often not possible to directly compare results across studies and materials due to differences in methodology.

Results from the work by Roy, Porterfield, and Hobson at UVM for Vermont materials are comparable to previous studies. Their preliminary data, which include particles > 0.5 mm, show plastic contents of less than 0.1% w/w TS for 20 composts and a digestate derived in part from depackaged ice cream pints, with plastic content not detected for some samples. Their results for depackaged food waste (either ice cream or source separated organics) have been variable but consistently less than 0.5% w/w TS.

Are Microplastics Regulated?

The inert components content of composts and digestates are regulated in several European countries. The threshold concentration of impurities in composted biowaste varies. The Austrian guidelines, for example, set the weight-based limit for plastics > 2 mm as 0.2% w/w TS. In Germany, this threshold is stricter (0.1% w/w TS). In Ontario, Canada, plastics in compost must not exceed 0.5% w/w TS (Lopes, 2019).

There is no national standard in the U.S. but many states with compost quality regulations limit the inert component content to 0.5% w/w. Inert components include plastics, glass, metal, rock and sand. For one cubic yard of finished compost with a bulk density of 900 pounds per cubic yard, that compost could contain up to 4.5 pounds of inert material, which many believe adversely affects compost market pricing.

Some states are beginning to think about regulating microplastics. In June 2022, Vermont Governor Phil Scott signed Act 170, which prohibits the Secretary of Natural Resources from issuing a new solid waste facility certification for a food depackaging facility or amending an existing solid waste facility certification that results in an increase of capacity at a currently certified food depackaging facility until the Vermont Agency of Natural Resources (ANR) adopts, by rule, requirements for the operation of food waste management facilities in the state. The genesis of this regulatory action was not as much concern over microplastics as it was concern over depackaging being used to process MSW instead of source separation. However, it brought attention to the microplastics issue.

One benefit of the legislation was that Act 170 required ANR to convene a collaborative stakeholder process to make recommendations on the proper management of packaged organics and to report those recommendations to the General Assembly. The convened Depackager Stakeholder Group consisted of seven individuals from various sectors with a stake in organics recycling in Vermont. Not surprisingly, the group failed to come to consensus on how depackaging (and, by extrapolation, MPs) should be regulated in Vermont, citing the need for more research and study.

In February 2023, ANR released a draft policy statement that notes, “After considering applicable statute, the intent of the Universal Recycling Law (Act 148 of 2012), the recommendations made by the Act 170 Stakeholder Group and evaluating the environmental impacts of food residuals management strategies being employed across the state including the value of source separation, it is the Agency’s policy that source separated food residuals shall not be mixed with heavily packaged food residuals at the point of generation.” While the policy will apply to generators, haulers and processing facilities, the bulk of the compliance burden will fall on generators who will have to separate lightly packaged food more suitable for manual depackaging from heavily packaged food amenable to machine depackaging.

In addition, the act required ANR to submit to the General Assembly a report regarding the prevalence of microplastics and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in food waste and food packaging in Vermont. This work is underway.

The transition from regulating inert content in finished composts and digestates to regulating the MP content of those products is mind-boggling in its complexity. Good policy and regulation should always be based on good science, and with MPs, good science is currently lacking in conformity of testing procedures, analysis procedures (and certification of laboratories in analyzing MPs) and reporting consistencies. These scientific shortfalls will be addressed over time.

Then, there are a myriad of other complications before regulatory action will be viewed as effective. Questions include:

- Should the compliance point for MP concentrations be in the feedstocks or in the final product?

- How can science shorten the time delay between compliance sampling and compliance reporting (now requiring weeks and, often, months)?

- What polymers are to be regulated, and, if any, where, why, and how? Are fibers, fragments, and filaments to be regulated in the same manner?

- Are regulations to be based on human health or environmental impacts (or both)?

As Dr. Roy commented in the February BioCycle interview, “I know our work will help practitioners better understand which polymer types are the most problematic in terms of abundance as well as, importantly, mass. Where I throw up my arms is where exactly should we draw the line on what we will accept from an ecotoxicological and human health standpoint? There are just so many unanswered questions and I think one challenge that I don’t see being overcome anytime soon is the variation and uncertainty in microplastic characteristics and impacts.”

What Lies Ahead?

Investigative work at the UVM Gund Institute for the Environment continues. Roy and his team have secured U.S. EPA funding with Dr. Matthew Scarborough to continue their work on characterizing MPs (with a focus on digestates and food and beverage waste). In a related project, Porterfield and Roy are conducting a life cycle analysis (LCA) of organic waste management that will consider microplastics. “We plan on using a LCA of a challenging food waste functional unit. Many previous studies have used one kilogram of food waste,” explains Porterfield. “Those studies have assumed that the food waste is pure and clean, and from everything we’ve learned, that is rarely the reality on the ground. One question we will seek to answer is how do the LCA results change depending on the level of contamination?”

An overarching goal of the work at UVM is to help inform policy in organic waste management with data, leading to better outcomes for people and the environment. “I think, in the short term, MP regulation may remain a call based on aesthetics to some degree, for example what looks contaminated to a compost buyer,” noted Roy. “As we deepen our understanding of this issue, my hope is that we can better define not only MP impacts, but also best practices to mitigate those impacts while achieving the goals of organics recycling. A first step is to quantify the extent of the problem — and I think we have made good progress on that. But much more work is needed across the country and world on this issue in the years ahead.”

Craig Coker is a Senior Editor at BioCycle CONNECT and a Principal at Coker Composting and Consulting near Roanoke VA. He can be reached at ccoker@cokercompost.com