Nora Goldstein and Kat McCarthy

The NRDC’s (Natural Resources Defense Council) Food Matters initiative partners with cities to “achieve meaningful reductions” in food waste through the adoption of policies and programs that focus on preventing food from going to waste, rescuing surplus food, and recycling food scraps. Building on its experience working with individual cities such as Nashville, Baltimore, and Denver to minimize food waste, Food Matters moved into a new phase in 2020, addressing municipal food waste while leveraging regional synergies. In the Food Matters Regional Initiative, city representatives network with one another, with NRDC, and with local partner organizations to set goals, develop programs, and identify regional strategies that help maximize their resources.

A key component of the Food Matters initiative is peer-to-peer learning and knowledge sharing — providing a network in which best practices can be shared and evolved. To get a handle on best practices related to policies and regulations, NRDC commissioned the Center for EcoTechnology (CET), the Harvard Food Law and Policy Center (FLPC) and BioCycle Connect, LLC (working with CET) to survey food waste-related policies in 12 states across three regions of the U.S. (corresponding to the states represented in its Food Matters Regional Initiative). The three regions are the Mid-Atlantic, Southeast and Great Lakes, and include these states: Maryland, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Washington, D.C. (Mid-Atlantic); Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee (Southeast); Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin (Great Lakes).

Working closely with NRDC, CET, FLPC and BioCycle compiled an inventory and gap analysis of existing food waste-related policies for each state, divided into ten categories across the food recovery hierarchy: Organics disposal bans and recycling laws; date labeling; food donation liability protections; tax incentives for food rescue; organics processing infrastructure permitting; food safety policies for share tables; food systems plans, goals, and targets; plans targeting solid waste; climate action goals; and grants and incentive programs related to food waste reduction. Whereas the inventory provides an overview of existing state policies, the gap analysis identifies policy opportunities for furthering food waste reduction.

Detailed reports (each over 60 pages) — Food Waste Policy Gap Analysis And Inventory —were prepared for each region of policies and regulations across the ten categories. “The gap analyses identify particularly strong policies that can be leveraged to further a city’s food waste reduction goals, as well as advocacy opportunities where policies are weak or nonexistent,” explains Darby Hoover, NRDC’s Senior Resource Specialist, Food Waste Initiatives, Health And Food, Healthy People & Thriving Communities Program. “The goal of these reports is to equip cities, states, and policymakers with a comprehensive overview of their state’s respective policy landscape and how it helps and/or hinders efforts to reduce food waste. Our hope is that these inventories and analyses can provide a comprehensive overview of where individual states have already taken action, and where there are opportunities for additional steps at the municipal, state, or federal level.”

Gap Analysis

To conduct the gap analysis, the research team first completed the inventories for each state of current policies related to each category. The team also conducted interviews to fill in gaps and gain insights on the current landscape and potential opportunities. The policy inventories for each state (presented in tabular format) summarize (and provide links to) laws, tax incentives, liability protection for food donation, and other tools utilized in public policies related to the food waste hierarchy.

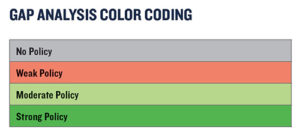

Next, the policies were analyzed and compared against a rubric that defines “No Policy,” “Weak Policy,” “Moderate Policy,” and “Strong Policy” for each category. Content from the policy inventories was analyzed and compared against this rubric to develop a consistent approach to apply a status to each policy for the gap analysis. To illustrate, we’ll use Organics Disposal Bans and Recycling Laws, Organics Processing Infrastructure Permitting, and Date Labeling as examples.

Next, the policies were analyzed and compared against a rubric that defines “No Policy,” “Weak Policy,” “Moderate Policy,” and “Strong Policy” for each category. Content from the policy inventories was analyzed and compared against this rubric to develop a consistent approach to apply a status to each policy for the gap analysis. To illustrate, we’ll use Organics Disposal Bans and Recycling Laws, Organics Processing Infrastructure Permitting, and Date Labeling as examples.

Organics Disposal Bans and Recycling Laws: These policies are described as “an effective means of achieving food waste reduction, including via prevention and other strategies across the hierarchy. By limiting the amount of organic waste that entities can dispose of in landfills or incinerators, organics disposal bans and waste recycling laws compel food waste generators to explore more sustainable practices like waste prevention, donation, composting, and anaerobic digestion (AD).”

Given that description, the strong, moderate and weak policy assessment for a state regarding bans and laws is:

- Strong Policy: Applies to all commercial generators (and possibly individuals at the household level) and is actively enforced.

- Moderate Policy: Similarly enforced but imposed only on select commercial generators.

- Weak Policy: Provides several exemptions from the law’s applicability, such as exemptions based on distance from a processing facility or the cost of processing.

Notes the report, “It is quite common for states to start with a Weak Policy and gradually strengthen it as the marketplace evolves and impacted stakeholders are educated and gain the resources to comply.”

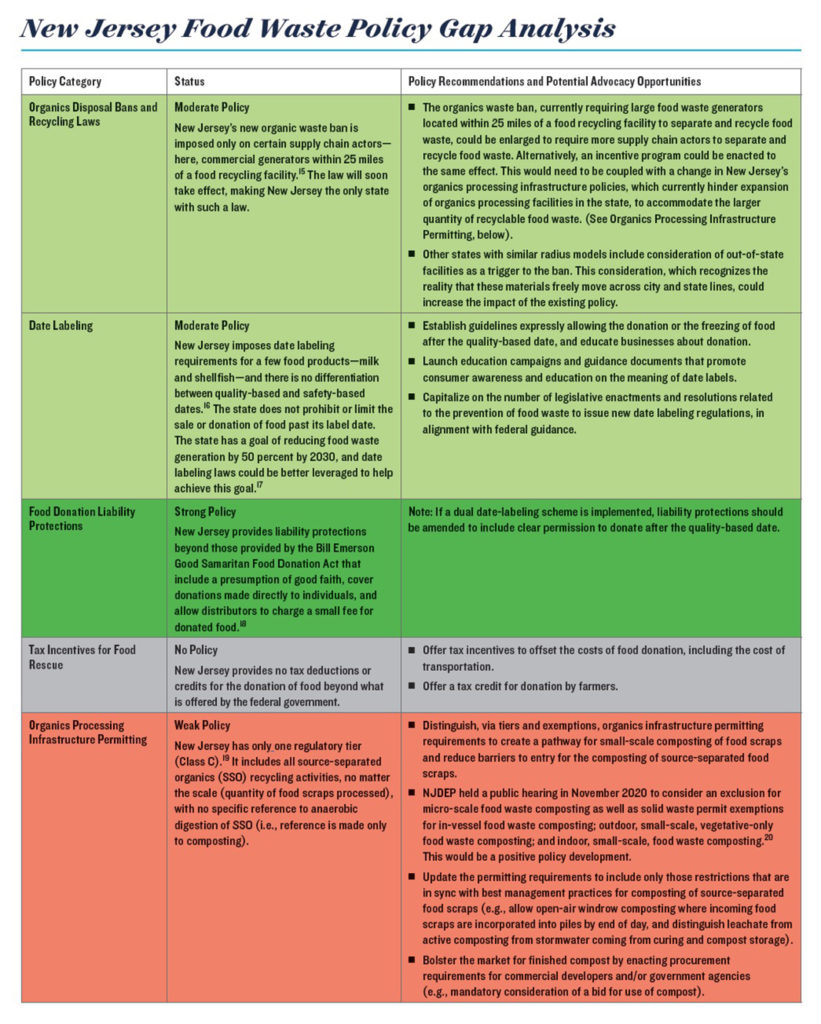

Mid-Atlantic Region

In the Mid-Atlantic region, for example, Pennsylvania has no organics ban policy or law. Recommendations offered in the analyses include pursuing a ban/recycling law, or introducing a solid waste disposal tip fee to incentivize waste diversion and providing funds for revenue stream to fund food waste prevention. New Jersey, on the other hand, has a Moderate Policy. Its organics disposal ban is imposed on commercial generators within 25 miles of a food recycling facility. Suggestions in the report support looking beyond the 25-mile radius and/or considering out-of-state facilities to trigger the radius, since materials often travel across borders. New Jersey also could include more supply chain actors, or provide an incentive program. As changes are made, the state may also want to understand opportunities for supporting increased processing infrastructure by reviewing those policies.

Organics Processing Infrastructure Permitting: NRDC defines strong processing infrastructure policies as ones that actively facilitate the development and permitting of organic waste processing facilities — including both commercial-scale composting and AD facilities and small-scale composting operations — and are in sync with current best practices for organics processing. A Strong Policy includes a regulatory tier for source separated organics (SSO) and provides opportunities for market development. Further, a Strong Policy minimizes barriers to entry, is aligned with best management practices for composting SSO, and offers a separate permitting process for AD of SSO.

Organics Processing Infrastructure Permitting: NRDC defines strong processing infrastructure policies as ones that actively facilitate the development and permitting of organic waste processing facilities — including both commercial-scale composting and AD facilities and small-scale composting operations — and are in sync with current best practices for organics processing. A Strong Policy includes a regulatory tier for source separated organics (SSO) and provides opportunities for market development. Further, a Strong Policy minimizes barriers to entry, is aligned with best management practices for composting SSO, and offers a separate permitting process for AD of SSO.

A Moderate Policy similarly offers a dedicated regulatory tier for SSO and considerations for market development, but it may have the same composting requirements for SSO as for mixed solid waste, may negatively impact economic viability by limiting the quantity or site acreage, or may include vague language for handling SSO through AD. A Weak Policy still includes a regulatory tier for SSO, but two of the drawbacks noted above (e.g., limitations on site acreage) are present. No Policy refers to locales with no processing tier for SSO, no acknowledgment of AD of SSO, and no exemption tier for small quantities of SSO.

Great Lakes Region

In the Great Lakes Region, Ohio is characterized as having a Moderate Policy. The state has separate permitting tiers for SSO and has simplified permitting for facilities accepting food scraps. It also has an exemption for small composting projects and raised the maximum processing threshold in 2018. The Ohio Environmental Protection Agency has determined that AD permitting falls under applicable air and water pollution control rules. Recommendations include: Develop a separate permitting pathway for AD of source separated food waste that includes, where applicable, requirements similar to those imposed on composting source separated food waste; and Bolster the market for finished compost by enacting procurement requirements for commercial developers (e.g., mandatory consideration of a bid for use of compost).

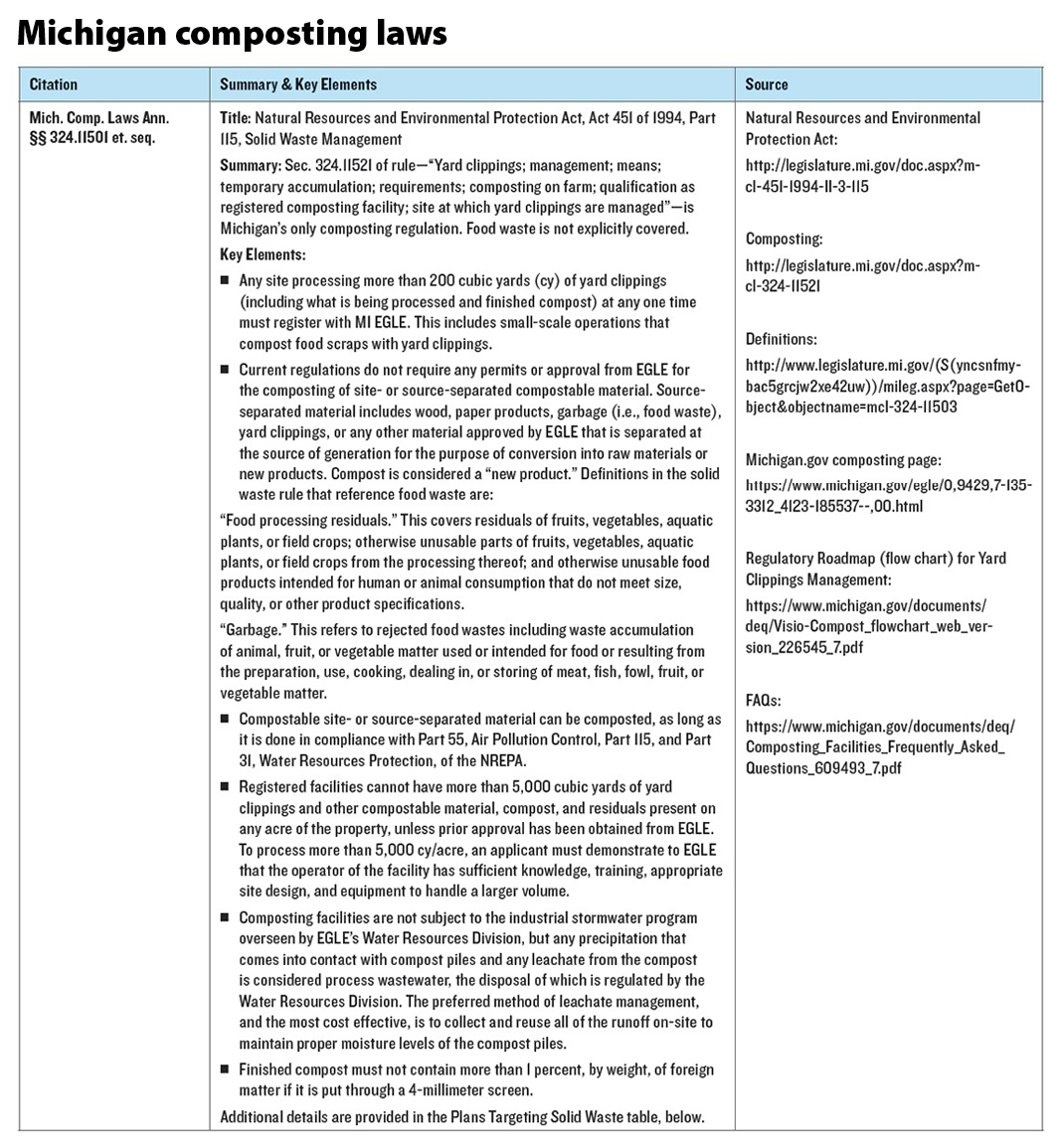

Michigan is categorized as having a Weak Policy. The state does not have separate regulations for food scraps composting. Permitting for yard trimmings composting facilities is not required, though registration with the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (MI EGLE) is required for facilities processing more than 200 cubic yards (cy) of yard trimmings. Food scraps can be incorporated at these operations. Registered facilities must seek MI EGLE permission to process more than 5,000 cy/year, likely affecting the economic viability of some composting operations. Michigan regulations do not reference AD.

Recommendations for Michigan include: Create regulatory tier(s) for food scraps composting; Increase the threshold volume of composted material that can be processed to reduce barriers to entry for composting source separated food waste; Develop a separate permitting pathway for AD of source separated food waste that includes, where applicable, requirements similar to those imposed on composting source separated food waste; and Bolster the market for finished compost by enacting procurement requirements for commercial developers and/or government agencies (e.g., mandatory consideration of a bid for use of compost).

Date Labeling: There is currently no federal system regulating the use of date labels such as “sell by,” “best by,” and “use by” on foods. Instead, each state individually decides whether and how to regulate date labels. NRDC’s definitions used in the rubric for date labeling are:

Date Labeling: There is currently no federal system regulating the use of date labels such as “sell by,” “best by,” and “use by” on foods. Instead, each state individually decides whether and how to regulate date labels. NRDC’s definitions used in the rubric for date labeling are:

- No Policy: There are no laws pertaining to date labels on food products

- Weak Policy: The state requires date labels for certain foods and prohibits or limits the sale or donation of food after its label date.

- Moderate Policy: The state requires date labels for certain foods but does not prohibit or limit the sale or donation of food after its label date.

- Strong Policy: The state maintains a standardized, mandatory date labeling policy that clearly differentiates between quality-based and safety-based labels; the state does not prohibit or limit the sale or donation of food after its label date; and the state has issued clear permission to donate after the quality-based date.

Southeast Region

In the Southeast region, Florida, Georgia and Tennessee are characterized as having “weak” policies for date labeling. For example, Georgia imposes date labeling requirements on eggs, milk, infant formula, shucked oysters, and any food requiring time/temperature control for safety or food labeled “keep refrigerated.” It further notes that “expiration date” is synonymous with “pull date,” “best-by date,” “best before date,” “use-by date,” and “sell-by date,” and thus does not clearly distinguish between quality and safety, which likely increases waste. Georgia also prohibits the sale of certain foods past their label date. Among the recommendations for Georgia is to remove the prohibition on offering milk and eggs past the sell-by date.

North Carolina’s policy is characterized as “moderate.” The state imposes date labeling requirements (date shucked or sell-by date) only on shellfish. The date labeling laws neither explicitly prohibit nor expressly allow past-date food donation. Recommendations to strengthen the policy include: Establish guidelines expressly allowing the donation or the freezing of food after the quality-based date, and educate businesses about donation; Launch education campaigns and guidance documents that promote consumer awareness and education on the meaning of date labels; and Capitalize on the number of legislative enactments and resolutions related to the prevention of food waste to issue new date labeling regulations, in alignment with federal guidance.

Accessing The Reports

This summary of NRDC’s new Food Waste Policy Gap Analysis And Inventory for the Mid-Atlantic, Southeast and Great Lakes regions just scratches the surface of the treasure trove of information and analysis in the three reports. Each can be downloaded from this page on NRDC’s website. Details about the Food Matters Regional initiative can be found at this link.

The cities participating in the Mid-Atlantic regional cohort are Baltimore, MD; Jersey City, NJ; Philadelphia, PA; Pittsburgh, PA; and Washington, DC. In the Southeast, cohort members are Asheville, NC; Atlanta, GA; Clean Memphis in Memphis, TN; Nashville, TN; and Orlando, FL. The Great Lakes participants are Chicago, IL; Cincinnati, OH; Madison, WI; Make Food Not Waste in Detroit, MI; and The Solid Waste Authority of Central Ohio.

Nora Goldstein is Editor/Publisher, BioCycle Connect, LLC. Kat McCarthy is an Environmental Specialist with the Center for EcoTechnology