Top: Photo courtesy of BigReuse, New York

e

Aaron Whittemore and Georgine Yorgey

In the U.S., recent decades have seen slow but steady progress in the use of anaerobic digesters to process varied organic waste streams including food waste, manure, wastewater, and municipal solid waste. With the renewed focus on the multiple negative impacts of food waste — greenhouse gas emissions, wasted energy and nutrients — interest has increased in digesters that incorporate this organics stream. To capitalize on the momentum surrounding anaerobic digestion technology, and explore ongoing barriers to increased implementation, researchers from the Washington State University Center for Sustaining Agriculture and Natural Resources carried out an EPA-funded project to assess possibilities for food waste anaerobic digestion (AD) in the state of Washington. Specifically, the team focused on identifying barriers and benefits to collaborative AD projects that could incorporate food wastes. The project was also interested in helping foster connections between stakeholders interested in pursuing AD as an organic waste management strategy.

Locations outside of the Seattle-Tacoma metro region were prioritized to assess AD opportunities in geographic areas that may not receive priority attention. The team ultimately chose three distinct areas with a number of individuals who were actively exploring AD and/or organic waste management, and that possessed differing attributes that made each a potential candidate for future digester projects. The first, the City of Spokane, has a population of 230,000. The city provides a comprehensive solid waste management system, including an optional curbside service to collect and compost yard trimmings and food scraps.

Locations outside of the Seattle-Tacoma metro region were prioritized to assess AD opportunities in geographic areas that may not receive priority attention. The team ultimately chose three distinct areas with a number of individuals who were actively exploring AD and/or organic waste management, and that possessed differing attributes that made each a potential candidate for future digester projects. The first, the City of Spokane, has a population of 230,000. The city provides a comprehensive solid waste management system, including an optional curbside service to collect and compost yard trimmings and food scraps.

The second area centered on the City of Yakima (population 97,000), and surrounding Yakima County (population 257,000). Like Spokane, the City of Yakima offers a comprehensive solid waste service that includes curbside garbage and recycling collection. However, there is no city-run program that offers composting services for food waste. A small, independent business has begun collecting food waste from individuals and businesses for composting in the area, but the number of subscribers to this service is low. Outside city limits, no curbside recycling or compositing services exist.

The Olympic Peninsula, and specifically Clallam and Jefferson Counties (population 111,000), was chosen as the third location because it is more rural and isolated than the first two study locations, yet still had interest in exploring improved organic waste management. The numerous towns within the region operate their own waste management services that vary in their offerings. Composting programs exist in some municipalities, and several operations are in place to provide organic waste to farmers which they use for animal feed or compost themselves to use as soil amendments. AD was gaining traction in the area as another means to divert even more organics from the Peninsula’s transfer stations and reduce the amount of material that is ultimately hauled to a landfill in Oregon. Increased organics diversion would be especially helpful during the summer season when tourists flood into the Peninsula for recreation and vacation.

Stakeholder Engagement And Feedback

Individuals and organizations interested in organic waste management and/or AD (solid waste managers, business owners, farmers, community leaders, etc.) were identified in each location; interviews and surveys were conducted to assess their perceptions of AD and gauge potential for new AD projects. During stakeholder interviews, benefits of AD identified by participants across study areas were generally similar, with some of the most cited being waste reduction and environmental benefits, usefulness of byproducts (i.e., digestate as a soil amendment, biogas for energy production), and potential for revenue generated by an AD system. All regions were also keenly interested in the potential for collaborative AD systems that could collect waste from various sources and provide an outlet for waste from a substantial proportion of residents and/or industries.

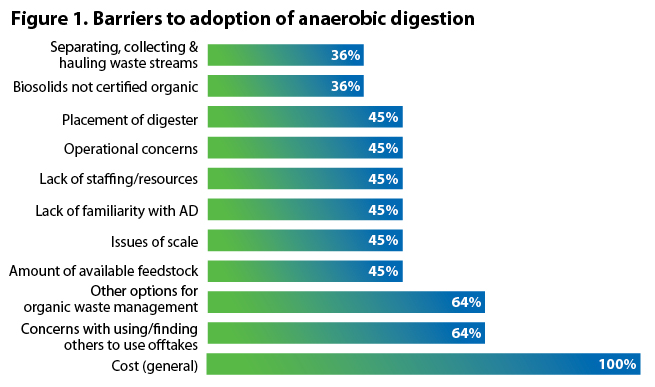

Barriers identified, and frequency at which they were cited, are captured in Figure 1. Unsurprisingly, one barrier consistently mentioned across locations was the cost of AD systems. They can be expensive with both substantial capital costs — the fixed, one-time expenses of designing and constructing an AD system — and operational costs, which include ongoing maintenance and monitoring that will require staff time, equipment repair and replacement, and depending on the configuration, costs associated with upgrading the initial biogas and digestate into more refined products.

Other barriers were driven largely by each area’s unique local context — and were not consistent across locations. In Spokane, determining the ownership and operation and maintenance responsibility of a regional AD facility across multi-jurisdictional entities was identified as the primary barrier, with siting the facility a close second. Permitting and a complex, lagging and/or siloed regulatory process were also perceived as potential hurdles.

Other barriers were driven largely by each area’s unique local context — and were not consistent across locations. In Spokane, determining the ownership and operation and maintenance responsibility of a regional AD facility across multi-jurisdictional entities was identified as the primary barrier, with siting the facility a close second. Permitting and a complex, lagging and/or siloed regulatory process were also perceived as potential hurdles.

In Yakima, barriers centered around a relative lack of knowledge of AD systems. Consequently, finding stakeholders who were willing to take a leadership role in exploring the idea and potentially owning and operating the digester was difficult. There was also concern about the ability to maintain high quality feedstock and appropriately monitor the system to ensure that the digester was functioning well, even among those who had some knowledge of AD.

On the Olympic Peninsula, concerns centered on finding a use for AD byproducts as there is no natural gas pipeline on the Peninsula that would allow for incorporation of refined AD-generated biogas (e.g., renewable natural gas) into the system. While digestate from AD can help improve soil health and productivity, many farmers already have access to compost or other soil amendments. Compared to the other regions, the Olympic Peninsula had more ongoing organic waste management operations, including a popular composting facility run by one of the local municipalities and a business that diverts food waste from local grocery chains. As a result, concerns were expressed that the need for AD may not be strong enough to garner the necessary support to start a region-wide AD system.

AD Potential

These examples are just a few of many pertaining to how local context defined the barriers to AD in each region, as well as the overall context in which AD may come to serve a particular community. Across locations, these barriers highlight the fact that even when there is a lot of positive sentiment surrounding AD, finding a route toward system implementation is difficult — and that this is not limited just to costs, though that is certainly one barrier. In one location, one of the interviewed entities secured grant funding to support an AD project, but ultimately chose not to move forward because they were worried about taking on the longer term responsibility and risk associated with digester projects. In another location, one interviewee had acquired and begun using a small AD system to process waste from their business. However, the owner decided to sell the system after facing numerous hurdles related to operation. The system was more complicated to operate than anticipated, requiring excessive staff time, and the digester process became upset several times due to issues with feedstocks.

Divert’s Integrated Diversion & Energy Facility, under construction in Longview ((WA), is not in any of the areas studied by WSU researchers. When operational in 2025, the AD will have capacity to process 100,000 tons/year of wasted food from food retailers, agricultural food producers and industrial food manufacturers, as well as other generators. Rendering courtesy of Divert, Inc.

While these stories cast a negative outlook on the future of AD, there was still much positive sentiment around AD, and it is likely that AD projects could be viable in these focus regions and similar areas under the right circumstances. For example, a 100,000 tons/year food waste AD facility is being constructed by Divert, Inc. in Cowlitz County, west of Yakima County (see rendering above). From interviewing and collaborating with stakeholders in this study, a few key messages were distilled that could help support future collaborative AD projects in Washington and beyond.

1) Harness local community power and bring people together to assess possibilities for AD. After initial interviews, the team held a workshop on the Olympic Peninsula, which provided new insights that were not realized when talking to participants individually. Bringing people together that have a stake in organic waste management enabled key conversations and necessary clarification of priorities to occur.

2) Find a local champion to help push forward exploration of an AD project. While a single actor is unlikely to bring about the types of collaborative AD systems that were of interest to the stakeholders engaged through this project, having a key person or organization to take responsibility for a project could help break down some of the most common barriers, such as ownership and responsibility of digester operation, lack of knowledge about AD, and working through regulatory hurdles. Although the business owner who operated an AD unit had issues with the technology that caused operation to cease, the determination to acquire and run a digester created a promising opportunity. Initial plans incorporated a variety of feedstocks into the digester that originated outside of the business’ operations and were motivation to explore options for involving the broader community in diverting organic waste from the landfill. If digester operation had gone smoothly, this project could have been the genesis of a well-functioning AD system that could have grown over time.

3) Broadly support local communities in strategizing and exploring pathways for advancing organic waste management options. Community leaders were often interested in exploring both composting and AD. Even where community interest was strong, there was a lack of capacity to carry out pre-feasibility analysis to support organic waste management planning. This included exploration of potential funding opportunities to support digester development (especially salient given high costs) and the relevant regulations that a digester would be subject to (e.g., waste management, air and water quality). The time and energy required to support project exploration and implementation should not be overlooked, and outside support during the process can greatly help communities achieve their organics management goals.

4) Investigate opportunities to take advantage of pre-existing infrastructure and transportation networks during project exploration. The team spoke with a company that diverts organic waste from grocery stores and other retailers in the Olympic Peninsula (among other locations across the country) and sends it to a regional digester facility. They made clear that a key to their success was plugging directly into pre-existing facilities, transportation networks, and waste management processes. By using existing infrastructure and networks (e.g., placing a digester at an existing transfer station), some costly and difficult steps of starting a regional AD system can be avoided or simplified. Additionally, the time, energy, and know-how required to operate an AD system may be initially lessened by using existing networks, improving the likelihood of project success.

5) Assess if AD is truly the correct organic waste management solution for a given community’s need. This assessment is essential. While the technology is a great organics management option, it may not always be the best fit, depending on the community’s goals and capacity.

Anaerobic digestion can be a highly beneficial approach to managing organics, but its implementation is often not straightforward. By studying three distinct areas in Washington state, the study highlighted the importance of local context in determining the feasibility and success of AD implementation and identified some key messages that may be helpful for future collaborative AD projects. Our team’s hope is that insights from this study can help improve future implementation of AD and other organic waste management strategies in Washington and beyond.

Aaron Whittemore is a Research Associate with Washington State University’s (WSU) Center for Sustaining Agriculture and Natural Resources, where he has worked since 2020. Georgine Yorgey is the Associate Director of WSU’s Center for Sustaining Agriculture and Natural Resources, where she has worked since 2009.