Deerfield Academy has taken a slow but steady approach to diverting food scraps, compostable paper and pizza boxes on its campus.

David Purington

BioCycle December 2015

Students, faculty and staff at Deerfield Academy have access on campus to bins for compostables (left) and recyclables (right), leaving a small percentage of waste for the trash bin (center).

Deerfield Academy is an independent boarding school for grades 9-12 (and post-grads) in Deerfield, Massachusetts, with a campus population of around 650 students and 500 faculty and staff members. The campus has more than 30 buildings including a dining hall, two small cafes, and 16 dormitories. Approximately 120 faculty live on campus in dormitory-based apartments or single and two-family houses.

The school has been diverting kitchen prep and table waste from the dining hall for a number of years. Three times per week, a truck hauls organics from a 3-yard container to Martin’s Farm, a nearby commercial composting facility in Greenfield, Massachusetts. In addition, food prep and tray waste and disposable serviceware from two cafes were also being diverted. To make this possible, the dining services team had aggressively researched compostable products from forks to plates to condiment cups. (They are currently using items from seven different brands to balance cost and performance needs.)

In 2013, the school had completed an overhaul of its campus-wide recycling program and was looking to expand the composting program. It was decided to start with small, easy steps where the whole community could participate, in part so that faculty and staff would be able to lead and model best behavior as the student population changed from year to year. Four changes were made around the same time that allowed staff to reach many people with simple messages and get them comfortable with separation and diversion to composting as a new responsibility. Changes included:

All pizza boxes are sent to the composting facility. A few students are enlisted each term to transport boxes using a cargo bike to a central point for collection.

Pizza boxes: Teenagers eat a lot of pizza. The Academy’s trash and cardboard recycling reflected this — and also showed the steady conflict of deciding whether a pizza box is clean enough to recycle. The school made an across-the-board mandate that all pizza boxes would be collected for composting. Collection points were provided outside the dormitories. A few students were enlisted each term to haul the pizza boxes back to a transfer point using cargo bikes. The sheer bulk of the pizza boxes would have overwhelmed the existing organics dumpster’s capacity, so the school added another small organics container provided by Martin’s Farm.

Napkins: In the dining hall, students, faculty and staff clear their own trays after meals. Plates are put onto the conveyor to be scraped by dish crews, but napkins were going into a trash bin. It became evident that the vast majority of the trash bin contents were paper goods — which could be composted. Bin colors and sizes were adjusted and a station was set up for napkins, along with a small bin for miscellaneous landfill items. The transition was fairly quick and smooth. The key was educating people to keep their food waste on the plates (otherwise, it makes the napkin bins messy and too heavy).

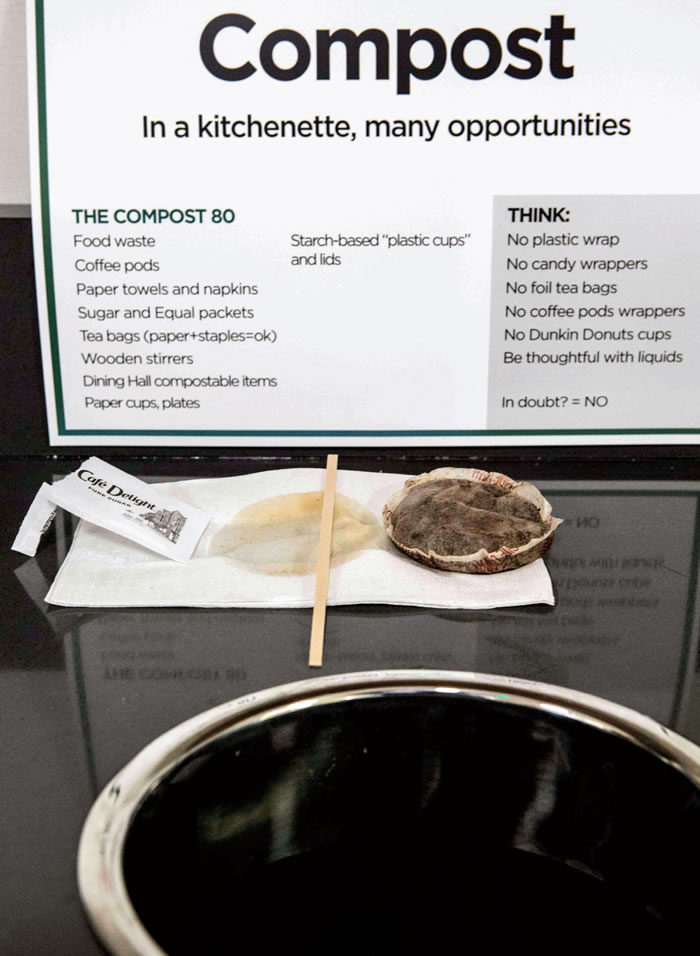

Coffee Stations: Coffee systems were switched to using compostable coffee pods (see photo) instead of the more common, plastic based single serve coffee capsules. This offered a significant reduction in waste (per cup, on a weight basis) from over 30,000-plus cups of coffee per year — and a huge number of opportunities for people to practice a changed behavior. Signs and a labeled compost bucket for “Coffee Pods Only” were added at each coffee station.

Faculty Houses: Live-in faculty was provided pails for kitchen food waste, which could be emptied in organics drop-boxes distributed around campus.

Coffee stations switched to using compostable coffee “pouches” (top right) instead of plastic single-serve coffee pods. Significant waste reduction was achieved, as 30,000-plus cups of coffee are consumed on campus annually.

Further Experimentation

With this broad experience taking hold across the campus community, facilities staff began to experiment with other ideas — all with the purpose of growing the program slowly, but always forward: plan carefully, troubleshoot quickly, and ensure things were functional for occupants and custodians before moving on to the next step. New initiatives included:

Bathroom Hand Towels: Napkin collection at the dining hall made it a small step to try collecting paper hand towels in a few trial bathrooms (at the facilities building and staff bathrooms at the dining hall). This has since spread to nearly the entire campus.

Classrooms: The science building has a food service cafe and a heavily used coffee station. In addition to organics collection in the public spaces, bins were added in all the classrooms and office spaces.

Library Goes All-Out: A change in the library director ushered in a new era — allowing food into the building. Being next door to the cafe, staff immediately rolled out building-wide organics collection, including in the bathrooms for hand towels.

New Construction and Public Spaces: Major renovations have been done on two buildings since the evolution to organics diversion. Both have been built with organics bins right alongside the containers/paper/landfill options. A few bins have been placed in outdoor spaces near food service facilities. These outdoor bins require timely attention to avoid pests and weather-related complications, but they send the right message.

Events: The Academy’s event planners expressed some concern about making a transition toward organics collection at events. After thoughtful design of signage and careful choice of bins (appearance, color and function), the school hosted a few small events that served as pilot studies. The transition went fairly smoothly from trepidation to success, and organics bins are now present at most events as a routine practice — even when hundreds of guests are in attendance.

Dorms As Next Frontier

Deerfield Academy has not been ignoring implementation of organics separation and collection in its dormitories. In 2013, many different options were evaluated for bins and handling strategies that would enable collection of compostables in the dorms when organics diversion was first being expanded. Ultimately it was decided to hold off due to concerns that a failed effort would have long-lived consequences on campus that could take years to overcome.

More recently, an ambitious student asked environmental staff to take on program implementation in the dorms. In turn, staff suggested that she lead the effort in one dorm as a pilot program. This presented a challenge for her to teach a broad set of stakeholders about bins and bags, roles and responsibilities. Her task was confounded by making the switch mid-year. However, she and the other students got the program underway, and organics collection continues today in that pilot dormitory. To accommodate this and other changes described in this article, the second organics bin from Martin’s farm has been upsized to 4-cubic yards and is now emptied twice per week.

But dormitory diversion remains a challenge. The pilot dorm was hand picked for success — it had the right mix of adults living and working there, and the right physical layout inside and out. The rest of the dorms will all have their special challenges, most particularly related to where to put more bins inside and out that keep the space livable and visually attractive.

This past fall, organics collection was added in the ninth-grade dormitories, so new students build the right habits from their first moments on campus. But the school has decided to wait for a group of student leaders to rollout to the rest of the dorms. This is an opportunity for a real-world group project to tackle a complicated problem with many stakeholders. And that’s exactly the kind of education Deerfield Academy hopes to deliver.

David Purington is the Environmental Management Coordinator at Deerfield Academy in Deerfield, Massachusetts, an independent boarding school with approximately 650 students.