The United Kingdom’s organics recycling industry is thriving as a result of pioneering legislation and a surge in source separation of household organics..

Tony Breton

BioCycle November 2012, Vol. 53, No. 11, p. 38

Since 1999, the central driver for the organics recycling industry across the European Union (EU) has been the Landfill Directive (99/31/EC). The Directive requires Member States, such as the United Kingdom (UK), to reduce the amount of biodegradable waste going to landfill to 35 percent of the 1999 level by 2016. To date, a number of different fiscal and regulatory measures have been introduced to ensure the UK meets its obligations. The most successful of these has been the landfill tax escalator, which is currently at £64 ($100) per metric ton and rising to £84 ($135)/metric ton in 2014. When combined with a median gate fee of £21 ($30) per metric ton (see Gate Fees Report at www.wrap.org.uk), municipalities will soon be facing average disposal charges of over £100 ($160) per metric ton.

When a municipality offers a food waste collection service, it normally provides a small container for the kitchen and a larger outdoor container (left) for separated food waste.

England

Officially, the waste policy for England is still the Waste Strategy 2007, but along with the change of government in 2010 came a review of waste policy that was published last year. The review contains a number of significant changes to the approach to waste and thus organic waste in England, including abolition of recycling targets for municipalities, cancellation of the landfill allowance trading scheme and a new strategy to promote anaerobic digestion. A new overarching waste management plan for England, as required by the European Commission has been put back to the end of 2013. Unlike the policies in Wales and Scotland (see below) the review in England contained nothing that could be considered ambitious and has been widely criticized as being weak. Steve Lee, the Chief Executive of the Chartered Institution of Wastes Management, described it “as interesting as half a sink full of dirty water.”

Wales

Published in 2010, “Towards Zero Waste” is the overarching waste policy for Wales and contains a wide range of measures, tools and targets for waste management until 2050. The policy will be implemented through a number of sector plans, each of which will see the introduction of new legislation and guidance. In the case of municipal organic waste, there are no specific targets but municipalities have a statutory requirement to recycle, compost or prepare for reuse of 70 percent of their waste by 2025.

The municipal sector plan includes a number of recommendations: a reduction in garbage waste containment capacity to 36 gallons with a collection frequency of no more than every two weeks, separate collection of food waste on a weekly basis with a preference for it to go to anaerobic digestion, and provision of food waste collection services for businesses.

The Welsh Government is currently consulting on how to measure recycling. For composting plants, in order to count as recycling, the compost must comply with the Compost Quality Protocol (or meet the EU’s End of Waste Criteria when enacted). Anything that does not meet the protocol (e.g. oversize, screenings, etc.) is not counted toward recycling. (To meet the Compost Quality Protocol, composters must demonstrate compliance with an accepted standard (the UK’s PAS100 is the certification available) and demonstrate the compost has gone to a beneficial market e.g. agriculture.)

For anaerobic digestion, if a plant has a dewatering operation then it must undertake extensive testing of the whole and dewatered digestate and calculate the loss of nitrogen and solids, and then deduct the lower value from the overall input tonnage. Apart from being onerous and expensive, this may in fact have a detrimental environmental effect as a recent life cycle analysis from Germany, released by the Federal Environment Agency, has demonstrated that aerobically stabilized digestate (which requires some dewatering) has a better environmental profile than raw (unseparated) digestate spread straight to land.

Scotland

The Zero Waste Scotland Plan was launched in 2010 and subsequently the Waste (Scotland) Regulations were introduced in May 2012. The regulations will have far reaching implications for the collection of organic waste in Scotland because they require all local authorities to provide separate food waste collection (not commingled with yard trimmings) to all households in nonrural areas by 2014. At the same time, food waste from businesses generating more than 50 kg (110 lbs)/week must be collected separately and by 2016 this requirement will apply to all businesses generating more than 5 kg (11 lbs)/week of food waste.

To reinforce these requirements and maximize the amount of food waste being separated for organics recycling, use of in-sink macerating units in nonhousehold premises such as municipal buildings, hospitals, hotels and commercial premises, and the deposit of food waste into the sewers, will be banned, starting in 2016. Additionally, Scottish Water has stated that the disposal of food waste into the sewer network increases the “risk of blockages, sewer flooding, environmental pollution, odors and rodent infestations.” Both Water UK and Scottish Water also have said that the loss of flow capacity and associated risk of flooding caused by the buildup of fat, oil, grease and other debris is already a major concern and something that the sewer network was never designed to deal with.

Northern Ireland

The Department for the Environment recently launched a consultation on a revised waste management strategy, “Delivering Resource Efficiency.” The document is fairly generic and contains a proposal for a statutory recycling rate of 60 percent by 2020. It also proposes to introduce an obligation on District Councils to provide receptacles for separate collection of food waste from households, a requirement on all food waste producers to source segregate food waste, and a ban on separately collected food waste being landfilled.

Organics Collection Trends

Separate collection of food waste in the UK has seen significant growth in recent years. For many years, the vast majority of municipalities provided a free weekly or every two weeks collection of yard trimmings, mainly in wheeled bins, but also using reusable, paper and compostable bags. However, in recent years, due in part to a reduction in local government funding and as part of a reconfiguration of collection services, a growing number of municipalities are introducing charges for their yard trimmings collections.

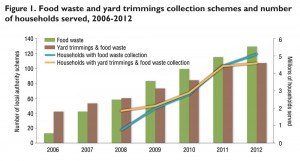

Because of the variety of policy and fiscal measures noted, the focus now for many municipalities is food waste. Initially, the trend was to encourage households to add their food scraps to their yard trimmings, but for economic and performance reasons the trend is very much towards separate collection of food and yard trimmings. Figure 1 shows the number of municipalities operating separate food and commingled food and yard trimmings services and the respective estimated number of households served. In total, over 5 million households receive weekly separate food collection and 4.5 million have commingled food and yard trimmings collection.

Because of the variety of policy and fiscal measures noted, the focus now for many municipalities is food waste. Initially, the trend was to encourage households to add their food scraps to their yard trimmings, but for economic and performance reasons the trend is very much towards separate collection of food and yard trimmings. Figure 1 shows the number of municipalities operating separate food and commingled food and yard trimmings services and the respective estimated number of households served. In total, over 5 million households receive weekly separate food collection and 4.5 million have commingled food and yard trimmings collection.

When a municipality provides a food waste service — either separate or commingled — it will normally provide a small container (1.5 gallons) for the kitchen and a larger outdoor container (5-6 gallons) for separated food waste. Following the advice of the Waste and Resources Action Programme (WRAP) based on its food waste collection trials, at the start of the scheme the vast majority of municipalities provide compostable liners which, if they are going to be composted in a PAS100 process, must be independently certified to EN13432 (the EU equivalent of ASTM D-6400). If a municipality decides it is not able to continue to provide liners then a number of retail options exist, including resale by the municipality. Certain branded products are carried in small retail stores for general purchasing. An alternative to compostable liners is compostable shopping bags (see sidebar).

Besides the economic reasoning for separating the containment and collection of food waste and yard trimmings (see “Source Separation Trends In The UK,” September 2009), there are also compelling performance reasons. As shown in Table 1, the amount of food waste diverted into the food waste collection will depend on the frequency of the garbage collection and how the organics are collected. Households with biweekly (every other week) collection set out an average of 1.5 kg/hh/wk compared to 1.3 kg/hh/wk for households with weekly garbage collection.

In conclusion, while it is clear that separate collection of food waste and yard trimmings in Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland will continue to be driven by specific policies and government funding, the same clarity is not present in England. In England, the preference of the coalition government is for a return to weekly garbage collection whereas the preference of the municipalities is trending towards garbage every two weeks with a weekly collection of organics.

Tony Breton is a UK-based separate collection and recycling consultant with Novamont SpA, Ital;. tony.breton@novamont.com.

WRAP Reports Cited

WRAP “Annual Gate Fees Report,” www.wrap.org.uk/content/wrap-annual-gate-fees-report

WRAP “Local Authority Separate Food Waste Collection Trials,” www.wrap.org.

uk/content/local-authority-separate-food-waste-collection-trials

WRAP “Performance Analysis Of Mixed Food And Garden Waste Collection Schemes,” www.wrap.org.uk/sites/files/wrap/Food_

Garden_Waste_Report_Final.pdf