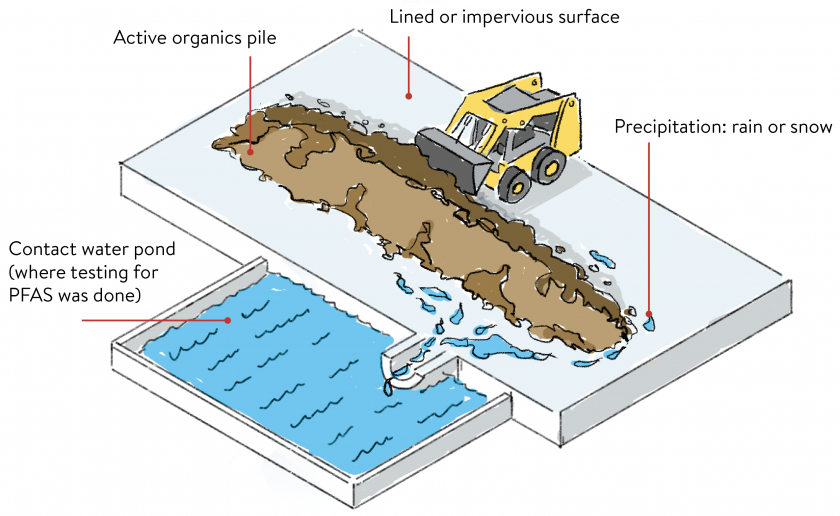

When the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) adopted its revisions to the state’s composting regulations in 2015, a distinction was made between contact water and storm water at composting sites. Contact water is defined as water that generally comes into contact with tipping and mixing areas, and active or early stage composting activities. Water from curing or finished compost is typically defined as storm water.

Image courtesy Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

In 2017 the Minnesota Department of Health set new standards for PFAS levels in drinking water. The standards apply to some types of PFAS and set low allowable concentrations (in the parts per trillion). Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) are a group of widely used synthetic chemicals found in many products, including non-stick cookware, commercial household products, cosmetics, food packaging, firefighting foam, and waterproof clothing carpeting and furniture. PFAS never break down in the environment, and are harmful to human health. Commercial composting sites accepting only organic wastes such as food waste, compostable food packaging and yard trimmings are likely to find PFAS in their feedstocks. As PFAS enter the waste stream, these chemicals create challenges in managing water runoff from compost sites (contact and storm water) and landfills (leachate) as well as at wastewater treatment plants.

Given these new health risk thresholds, and the compost industry’s desire to have alternative contact water management options, the MPCA decided to gather more data on PFAS concentrations in contact water. MPCA requires composters to test their contact water for PFAS, and other potential pollutants. Test results sometimes showed PFAS concentrations at or above the current solid waste program intervention limits.

To learn more, MPCA commissioned a study to evaluate PFAS concentrations in contact water. The study, conducted by Wood Environment & Infrastructure Solutions, Inc., collected data from five source separated organics materials (SSOM) facilities and two yard trimmings composting sites. The study included three sampling events and evaluated up to 29 different PFAS compounds at each site.

Background

Minnesota currently has 9 large-scale composting sites permitted to accept food waste (SSOM facilities), and more than 115 sites that accept yard trimmings only. The state would like to encourage more composting of food scraps, yard trimmings and other organic material. There are many environmental benefits to composting organics, including reducing greenhouse gas emissions and supporting improved soil health. Yard trimmings facilities and SSOM facilities are subject to different environmental regulations:

- Composters that accept only yard trimmings are not required to collect and treat water that comes in contact with yard trimmings. Instead, these facilities are designed to minimize water run-on and run-off. Yard trimmings facilities are prohibited from discharging storm water runoff to waters of the state.

- Composters that accept food scraps and compostable products are required to collect and treat contact water (water that has come in contact with organic material during the early stages of composting). Most SSOM composting facilities manage their contact water by sending it to a wastewater treatment plant or by reusing it in the feedstock mixing process for moisture addition.

Facilities designed and operated prior to the MPCA rule revision may not have design features or operational practices in place to separate the two types of water. Contact water must be collected in lined ponds and treated; however, storm water ponds are generally unlined, and the water is allowed to infiltrate but managed in accordance with site-specific requirements established under the terms of an industrial storm water permit. Although sampling SSOM contact water was the primary objective of this investigation, storm water sampling was also conducted at several facilities where more than one pond was present.

Preliminary Results

The study confirmed the presence of one or more PFAS chemicals at concentrations above intervention limits at all SSOM and yard waste sites sampled:

- At the SSOM facilities, the detected PFAS included PFBA, PFPeA, PFHxA, PFHpA, PFOA, PFNA, PFDA, PFBS, PFHxS and PFOS.

- For the yard trimmings sites, the detected PFAS included PFBA, PFPeA, PFHxA, PFOA, PFBS, PFHxS, and PFOS.

- At every composting site in the MPCA study, at least one sampling event revealed a PFAS analyte that was over the applicable Health Risk Limit (HRL) or Health Based Value (HBV).

The study compared PFAS concentrations with published data on ambient background levels, and found that PFAS concentrations at the SSOM and yard trimmings sites were generally greater than reported ambient concentrations of PFAS in groundwater across Minnesota. The study also compared PFAS concentrations from Minnesota composting sites to PFAS concentrations in leachate from landfills in Michigan. Generally, PFAS concentrations were lower at Minnesota’s compost sites than the reported data for landfill leachate in Michigan.

MPCA Recommendations

The MPCA release summarizing the findings included the following recommendations:

- For composting facilities: All SSOM composting sites should continue to direct contact water to wastewater treatment plants. Land application of untreated contact water is not viable currently unless onsite treatment or feedstock restrictions can lower PFAS concentrations.

- For policy makers: To reduce risk of products containing PFAS entering composting facilities, policy makers should consider limits or bans for PFAS in consumer products and industrial uses.

- For consumers: Continue composting. As long as PFAS is produced and discarded, we will find these chemicals in all areas where we discard things (landfills, wastewater treatment plants, etc.)

Composting itself does not create PFAS, and composting has many environmental benefits.

Overall, notes MPCA, “more research is needed to understand the sources, amounts, and impacts of PFAS at composting sites and in contact water, as well as potential treatment options.” The agency adds that the study also raises additional questions that need answering:

- What are the specific sources of PFAS in compost and yard trimmings?

- How much variation is there in concentrations of PFAS at SSOM facilities and yard trimmings sites?

- Are there seasonal variations in PFAS levels in contact water?

- What is the best way to screen for PFAS at composting and yard trimmings sites?

- Are there alternative strategies for treating contact water to reduce PFAS concentrations? What technologies are currently available?

- How does this data compare to other PFAS and composting research, including the MPCA’s groundwater monitoring adjacent to two Carver County composting sites in 2017-2018?

- Is PFAS making its way into final commercial compost products?

- What are PFAS concentrations in surface waters and storm water ponds and in other settings where there are ambient levels of PFAS?

Editor’s Note: The content of this article was excerpted from the following documents:

- Composting And PFAS

- Final Report: Investigation of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances at Select Source Separated Organic Material and Yard Waste Sites