“It is now to the point that if you don’t have a successful recycling program, you’re in the minority,” says Martin Tull, Executive Director of the Green Sports Alliance.

Marsha W. Johnston

BioCycle July 2013, Vol. 54, No. 7, p. 20

With few major obstacles, the potential growth for composting and waste recycling represented by the greening of the $450-billion professional sports sector is clearly enormous. “All industries meet on a baseball field — waste, water, plastics, utilities, everything,” says Allen Hershkowitz, Senior Scientist at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) and director of its Sports Greening Project. “This is a golden age for environmental reforms for stadiums and arenas at both the professional and collegiate level. It introduces the vocabulary of environmental stewardship, and of recycling and composting, to 20 million people every week.”

A handful of teams, like the Philadelphia Eagles, Seattle Mariners and Portland Trail Blazers, in collaboration with NRDC, began taking a hard look almost a decade ago at the mountains of waste their games generated. But they were the exception to the rule. At that time, nearly all of the 15,000 to 25,000 tons of noncompostable plastics, food and paper generated by a 50,000-person stadium at every event was hauled to a landfill.

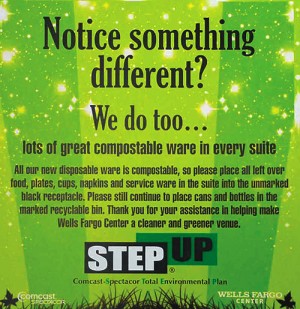

The Wells Fargo Center, home of the Philadelphia Flyers and Philadelphia 76ers, added front-of-the-house organics collection to its back of the house program in 2011. Photo courtesy of Comcast Spectacor

“It is now to the point that if you don’t have a successful recycling program, you’re in the minority,” says Martin Tull, Executive Director of the Green Sports Alliance (GSA), which was founded in 2011 in conjunction with NRDC and Vulcan Sports and Entertainment. “Most of the programs have been set up within the last five years. The Eagles began work in 2003, so within 10 years, we have been able to go from just a few outliers to strong adoption across the industry.”

At the Portland Trail Blazers’ arena, post game crew collects recyclables. The Blazers were one of the first sports teams to collaborate with the NRDC on venue greening.

In fact, adds Tull, the abundance of excellent waste diversion examples has created some peer pressure to keep up with where the industry is headed. “Frankly, if you can save millions of dollars, why wouldn’t you?,” he asks. “It’s an incredible time if you are a commercial composter or service ware provider, because demand is growing and we should see it adopted at all sports facilities.”

Wells Fargo Center

At a panel on the greening of sports facilities at BioCycle’s 27th Annual West Coast Conference in San Diego in April, Gail Clark, Vice President of Project Development for Philadelphia-based Comcast Spectacor, detailed her firm’s decision to compost all organics generated, including meats and dairy, at its Wells Fargo Center, home of the Philadelphia 76ers and the Philadelphia Flyers. In a strong collaboration with Aramark, its food service supplier, and Waste Management that began last October, the Wells Fargo Center added front-of-the-house (all seats, concession stands and premium areas) organics collection to its back-of-the-house program from the kitchen and commissary that began in 2011.

To avoid requiring fans to change their practice of putting all trash into a single container, everything used at its concession stands is compostable. Recycling is done behind the concession counter, with all drinks poured into a compostable cup for the customer, and no outside recyclable containers are allowed into the center. On the concourse, fans simply put everything into a single bin that uses a clear green liner to clearly indicate its compostable status to arena staff. All Premium Seating locations have both the compostable bins and recycling containers, with signage telling these ticketholders what goes where. Recyclables from the concession stands and Premium locations are put in clear bags, while the Center’s small amount of remaining waste goes into black bags for the landfill. The Center’s compostable waste is taken to Peninsula Compost in Wilmington, Delaware.

Comcast Spectacor began measuring the impact of the change in January, and saw its diversion rate skyrocket from 7 percent in February 2012 to 63 percent one year later. By April, it had climbed to 70 percent, from 11 percent a year earlier. Spectacor measures its total waste stream but does not record the percentage of recycling versus organics.

Clark says Spectacor plans to roll out comprehensive composting and waste diversion programs at all 120 Global Spectrum (a Spectacor company) accounts that include arenas, stadiums and conference centers. “We are compiling data on all usage, including utilities, for all of our accounts, and when we get the numbers we’ll see the main areas of concern,” she explains. “We have just rolled out back-of-the-house composting for maybe 25 percent of the Global Spectrum venues. We feel like we have the system down pretty well with numbers like (Wells Fargo Center’s), but you have to go in baby steps.”

Common Elements

The elements common to all sports venue greening programs, says Tull, are strong working relationships with the team’s food and beverage provider, waste hauler and municipal government and agencies. “These programs require thoughtful collaboration,” he notes, adding that GSA has noticed “a significant increase” in interest for both back-of-the-house and front-of-the-house composting programs at sports venues nationwide. But specific sorting strategies and types of compostable materials vary widely by venue and municipality. “Some have two bins, some have four, some encourage fans to sort at a station and others have fans leave things on the floor or stands of the venue, and the staff sorts it in the back of the house. Many have back of house composting in kitchens, but not in full concessions.”

The increased interest in zero waste initiatives and composting at sports venues can be attributed to a couple of factors, says GSA’s Tull. “There is a low barrier to entry, to begin doing back-of-the-house composting. It’s low cost, and there may be an immediate cost savings. There are so many success stories of facilities with programs that have been in place for three, four or five years, and a number of partners are quite skilled in this, such as Aramark, Center Plate and Levy Restaurants, also Allied and Waste Management.”

A number of the facilities adopting waste diversion and composting have seen nearly 50 percent waste diversion improvement in just a few years, Tull continues. “There are best-in-class facilities in all leagues and they are geographically distributed. Teams in the Midwest are outperforming those on the West Coast. There is still a perception that it is limited to certain parts of the country, but that’s just not the case.”

GreenDrop sorting stations use colorful graphics to depict the items appropriate for discard in each bin. Images courtesy of GreenDrop

The trend is national and across leagues, but as noted in Game Changer, a September, 2012 report from NRDC on advances in greening sports venues, some leagues are ahead of others. “Among all sports leagues, Major League Baseball has the best-developed environmental data measurement program, followed by the National Hockey League and the National Basketball Association,” the report says (see sidebar, Baseball: The Greenest League).

Although the National Football League’s (NFL) Eagles were ahead of virtually every team in any league, and the NFL set up a Green Team Committee with NRDC in 2008, professional football is playing a bit of catch-up to its fellow leagues. The NFL is not, for example, a member of the Alliance, although 10 NFL teams are listed on GSA’s member roster. Lyle Peters of GreenDrop Recycling, which makes integrated 4-bin stations (food waste/composting, glass, mixed recyclables (cans, plastic bottles) and landfill), explains that one of the NFL’s challenges has been that it has much fewer games, compared to baseball’s 162 or basketball and hockey’s 82, making the return on a waste diversion investment a harder sell. “The main NFL season is 16 games, 8 of which are at home, a couple of preseason, and a couple in post season,” says Peters. “[Football stadiums] will do a couple of mid-summer concerts, maybe a high school championship game,” adding that some stadiums will bring in major league soccer teams, but those often abandon the venue for a soccer stadium after a couple of seasons.

Hershkowitz of NRDC says the NFL has been preoccupied at the league level with concussions, noting that the person who ran the Green Team Committee left to run the league’s committee on concussions. “The NFL has more work to do,” he notes. “We’re in dialogue with them [and] hoping to see more initiatives. The Giants and Jets are doing great work.” The Kansas City Chiefs also began implementing and tracking sustainability efforts more than two years ago. Since then, the team has quadrupled its waste diverted from landfills through recycling, composting, and other means from 11 percent to 44 percent. And the Denver Broncos’ water conservation program has saved over 9 million gallons since 2008 (see sidebar, Denver Broncos Save Millions of Gallons of Water).

The Portland Trail Blazers, along with three professional sports teams in Seattle and the Vancouver Canucks, were the inaugural team members of the Green Sports Alliance.

Diversion “Tools”

Sports venues are using a wide variety of methods to collect organics from fans, including tools like the GreenDrop stations. The sorting points also provide an opportunity for education. For example, each of the 4 sections on the standard GreenDrop has a colorful graphic depicting the items appropriate for discard in each bin. “Graphics are key for accuracy and participation,” Peters explains, adding that having an integrated station where each stream is in the same position is also critical. If individual bins get placed in a different order after cleaning, for example, contamination rates will increase, he notes (see sidebar, Tips for Participation). The stations also provide teams a potential revenue stream with advertising space on the front panels.

Another key factor to success, says Tull, is that compostable service ware is commercial-ready, which was not the case even 5 years ago. “It’s cost-competitive, it works, and there are 15 different varieties, including bamboo and bagasse.” NatureWorks’ Davies agrees. A joint investment of Cargill and Thailand’s PTT Global Chemical, NatureWorks developed and manufactures Ingeo, a compostable plastic that it sells to makers of many products, including service ware, which was one of the first markets NatureWorks got into in 2003. It took several years to develop a big enough customer base for compostable plastic to convince the mainstream food service companies to adopt Ingeo, but since 2009, notes Davies, NatureWorks has supplied 7 of the top 10 thermoformers (compostable product manufacturers) in the U.S.

Even with the advances in compostable service ware, says Spectacor’s Clark, it took a lot of convincing of upper management at the Wells Fargo Center to replace high-end black plastics with compostables in Premium Seating “because people pay a lot of money for those box seats and there’s a perceived value.” Despite such resistance, Tull points out that compostable service ware is typically less expensive than high-end plastic plates, providing immediate cost reductions. Furthermore, he says, “every sports venue that has put compostable service ware in the suites has had not a single complaint. In fact, many fans like to be part of these solutions, rather than a hindrance, so it is an added element they can sell to their fans.”

Consequently, “in the last year, sports venues have been the biggest voice for compostable plastics,” says Davies. As a result, food service ware, which represents over a quarter of NatureWorks’ business, is growing “at a steady clip,” he notes. However, growth in the use of compostable service ware inevitably has increased the number of composters who report that a “compostable” plastic didn’t compost. To maintain its market momentum, NatureWorks’ Davies says the US Composting Council and Biodegradable Products Institute convened a working group of composters and plastics manufacturers to see if the ASTM 6400 standard for compostable plastics needs to be changed. “It was developed in the mid- to late 1990s from a survey of composting practices, which have probably changed,” he explains. “We’ve worked very hard to make our products indistinguishable from the products they replace, and what we typically find is that it wasn’t a compostable plastic at all, but polypropylene or PET, and can’t be recycled because it has food residue, and can’t be composted either.”

Composters such as Carla Castagnaro, founder of AgRecycle in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, have taken the matter into their own hands by publishing a list of service ware they will take because the company has certified that it is compostable. Davies notes that it is easier for a sports venue to control the service ware it composts than it is for a municipality, which must maintain an open loop.

Once a zero-waste program has been implemented, the items remaining for landfill include packaging brought in from outside the venue and straws and ketchup packets, which are common but mostly noncompostable, says Tull. “Some venues us e [condiment] pumps with condiment cups but that’s a policy decision.”

Some municipalities do not have composting facilities adequate to serve a stadium or arena, which could create an obstacle. But GSA sees this as only a short-term problem. “In every one of those markets, if you have a large number of sports facilities, hospitals, etc. and they want to do food composting, there will be composters willing to set up a facility,” says Tull.

Equally significant is the cultural impact that sports have in the U.S. NRDC is releasing a report in August, coauthored by Hershkowitz, on the greening of college sports facilities titled, “Collegiate Game Changers: How Campus Sport is Going Green” (see sidebar). The report points out that only 13 percent of Americans say they follow science, but 61 percent identify themselves as sports fans. “The influence of sports is enormous,” says Hershkowitz. “Think what Billie Jean King did for gender equality and Magic Johnson for the destigmatization of HIV AIDS. It’s a great honor to be working with professional sports leagues. The commissioners of basketball, baseball and hockey — David Stern, Bud Selig and Gary Bettman — are some of the most influential environmental stewards I’ve met in my 35-year career.”

Adds StalkMarket’s Chandler: “Generally speaking, when you talk to the public about recycling or composting, the message sticks with about 30 percent of the people. But when you associate that message with sports, when you have team members espousing it, that rate goes up to about 80 percent.”

Marsha Johnston is a Washington, DC-based freelance writer and communications consultant, specializing in sustainable development and conservation.