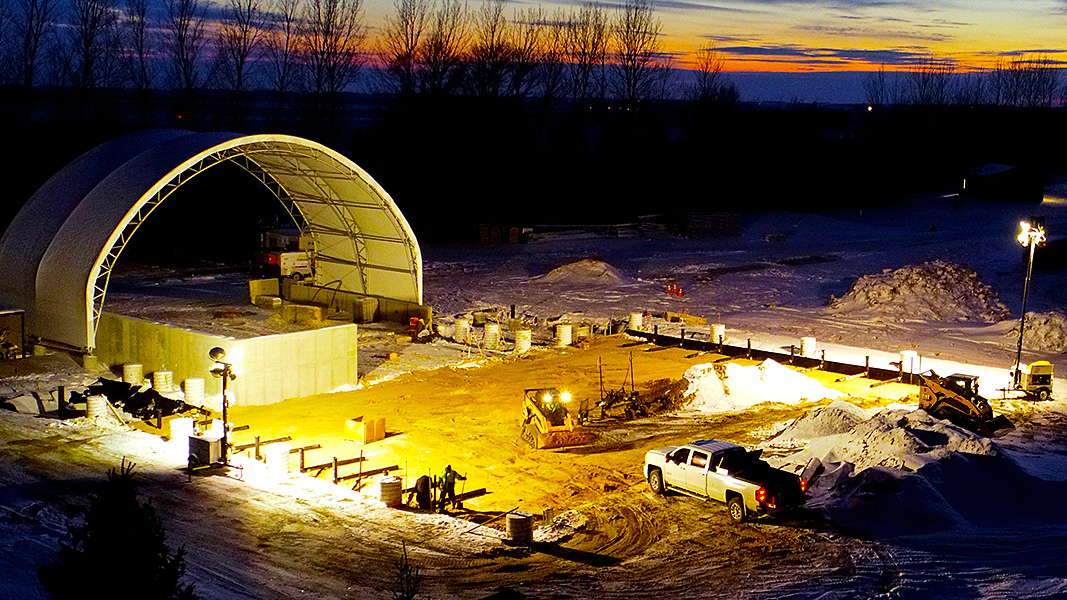

Top: The COMPOST Act, reintroduced in this session of Congress, would direct funding to construction of new composting infrastructure. Photo courtesy of Engineered Compost Systems

Alex Truelove

As climate change and pollution have become critical issues of our time, composting as a mitigation tool has emerged as a topic of interest among environmentally minded legislators and regulators — evidenced by the growing number of now enacted policies to support the composting industry. At the same time, organizations have dedicated resources to advocate on the industry’s behalf to ensure that this momentum continues.

While there are countless policies that affect the compost supply chain, from local permitting regulations to instituting international product biodegradation standards, three major policy areas have emerged that may make or break the U.S. composting industry over the next few years: infrastructure development, compost application and limiting contaminants.

Infrastructure Development

Underdeveloped composting infrastructure may be the single biggest obstacle preventing the U.S. from developing a healthy, circular bioeconomy. As BioCycle readers know, only a minority of Americans have access to curbside or drop-off organics collection programs, which means that most of the municipal organic waste goes to landfill where it generates climate pollution and fails to create compost.

Conversely, Canada and countries across Europe boast higher collection rates in part because they financially support the development and implementation of curbside programs and processing facilities. The U.S. is finally starting to catch on, as advocates have pushed for creative funding solutions to do the same.

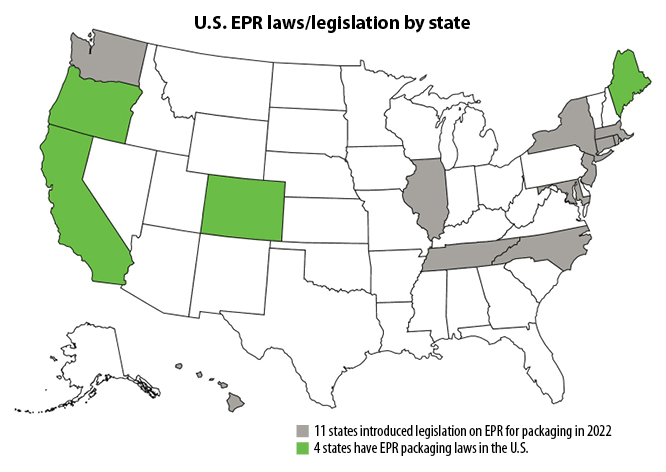

At the state level, no waste trend is hotter than extended producer responsibility (EPR) for products and packaging (including compostables). EPR programs levy marginal fees on single-use products like food packaging. Those fees in total are then redistributed to help manage the waste those products become. Products that are more recyclable, reusable, or compostable are often assessed lower fees than products that are destined for the landfill. This encourages product manufacturers to transition to more sustainable design practices over time to avoid higher fees. In just the past two years, four states have passed EPR legislation while a dozen other states have introduced similar bills.

Early EPR programs in Maine and Oregon levy fees on certified compostable products only to siphon that money towards non-composting activities. However, recent programs in Colorado and California ensure financial support for composting infrastructure and education and promise representation from the composting industry in program development (typically, the latter is achieved by appointment to a statewide advisory board).

As more states hop on the EPR bandwagon and these programs are activated, we’ll see new revenue streams become available to composters that choose to accept certified compostable products. Because certified compostable products represent only a small segment of all products and packaging, we shouldn’t expect EPR alone to generate all the revenue required to fully support organics collection and processing. To close the gap, creative ways will be needed to access funding from federal government programs.

One such program is SWIFR (Solid Waste Infrastructure for Recycling). Introduced last year, it directs the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to create grant programs for states and municipalities to boost their recycling and composting programs. While individual composters cannot apply, they can encourage local and state leadership to apply for funding to pass through. Similarly, the Biden-Harris administration recently announced new goals to advance the bioeconomy. While specific funding opportunities aren’t yet clear, avenues may emerge to support both the manufacturing and end use of (biobased) compostable products.

Congress will also need to play a role in establishing more permanent funding sources. The COMPOST Act, reintroduced in 2023, would provide $200 million/year for 10 years in grants and loan guarantees throughout the country. Because the Farm Bill, an enormous piece of legislation, is also on the docket this year, we may see the COMPOST Act inserted as a new program within, if advocates have their way.

Compost Application

Demand for finished compost drives the entire industry, but like many growing enterprises, it needs support. The recently passed Inflation Reduction Act includes funding through the U.S. Department of Agriculture for programs that include subsidizing compost application and provide technical support through the Natural Resources Conservation Service. While the industry deserves even more support, it’s a start.

The recently passed Inflation Reduction Act includes funding through the U.S. Department of Agriculture for programs that include subsidizing compost application on farms. Photo courtesy of Recology

Meanwhile, the federal National Organic Program standards prohibit composters from selling compost that contains certified compostable products for use in organic agriculture. Updating regulations to allow for certified (read: compostable and tested for PFAS and toxicity) products as an allowable input will provide compost manufacturers with access to new end markets.

Limiting Contaminants

California has required all produce and bulk bags in grocery stores to be reusable, recyclable, or compostable.

Contamination threatens the entire composting industry, in no small part because consumers and composters alike can’t distinguish compostable products from non-compostable “lookalikes.” While BPI offers free screened overs testing to composters to identify contaminants, more proactive solutions are needed to address the misleading terminology and confusing color and symbol schemes that populate shelves. That’s why states (California, Washington, Maryland, Minnesota) have begun to prohibit terms like “degradable” and “decomposable” on products that don’t adhere to the rigorous standards adhered to by certified compostable products.

Washington State has gone even further, requiring compostable products to use green, beige, or brown color and/or striping to distinguish themselves from non-compostables. Additionally, non-compostable film bags are prohibited from using such color schemes to reduce confusion. We should fully expect other states to adopt similar language, provided there is enough support. For example, SB23-253, “Standards For Products Represented As Compostable,” was introduced in the Colorado legislature this year. The bill is designed to align with Washington State by requiring products presenting as compostable to be certified by a recognized, independent, third-party verification body. Products not certified compostable would be prohibited from marketing or advertising the item using tinting, color schemes, labeling, images, or words that are required for products that are certified compostable — or using labeling, images, or words that could be reasonably anticipated to mislead consumers into believing that the product is compostable.

California has required all produce and bulk bags in grocery stores to be reusable, recyclable, or compostable. Because conventional plastics films bags are not considered recyclable, we expect to see stores across the state offer compostable bags that consumers can use not only to bag their apples, but also their apple cores for composting. Meanwhile composters can worry about one less conventional plastic contaminant.

While momentum currently favors industry growth, work is needed to ensure it continues. Advocates and practitioners have critical roles to play in the coming years as voices of support and expertise in legislatures and regulatory arenas.

Alex Truelove is legislation and advocacy manager at BPI. He previously directed U.S. PIRG’s (Public Interest Research Group) zero waste program.