Top: Pre-2007, curbside collection of fall leaves was highly efficient and yielded large tonnages in a short collection period. Photo courtesy S. MacBride

Samantha MacBride and Peter McKeon

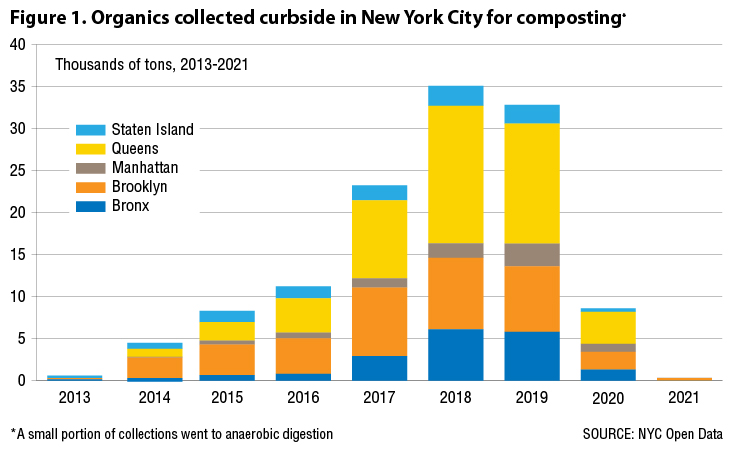

New York City’s curbside organics collection program, which includes household food scraps, compostable paper and yard trimmings, brought in 329 tons in 2021, as compared to nearly 35,000 tons at the program’s peak in 2018. In that year, curbside collection for buildings of nine units or fewer was in place in roughly two-thirds of the city’s 59 sanitation districts, all outside Manhattan. If you counted all the households served in those districts, the reach seemed impressive: people living in almost 400,000 units could — if they wanted to — participate in weekly setout of compostables in a brown bin issued by the New York City Department of Sanitation (DSNY). What is more, hundreds of 10+ unit buildings had enrolled in a supplementary program that required buy in from management, extending the reach of the program to another 40,000 households in all New York City (NYC) boroughs, Manhattan, Queens, Brooklyn, Staten Island and the Bronx.

But if you looked at the tonnage collected over the course of the program, it told a different story. Counting households served doesn’t tell you anything about who is participating — and lots of folks were not. Into the trash, and headed for landfills, went about one million tons of food scraps, compostable paper, and yard trimmings that could have, and should have, been collected and turned into compost as the highest and best use.

Looking at “capture rates” (tons of curbside organics collected divided by tons of curbside organics generated in total) on a district-by-district basis, several suburban areas in Eastern Queens, and Northern Bronx stood out as high achievers, as did Park Slope in Brooklyn. Using public tonnage data and results of the City’s 2017 waste characterization study, we calculated that a few areas garnered as much as 11% of the potential organics that should have been set out. In many other areas, the yield was far lower. Had the capture rate been calculated as a citywide total, it would have been on the order of 3.5% for 2019.

For comparison, the capture rate for paper, metal, glass and plastics in NYC recyclables is a bit over 50% on average citywide, and as high as 70% in some districts. Focusing on growing quantities of organics collected, rather than capture rates, obscured a lack of progress. As shown in Figure 1, tonnages of curbside organics collected through 2019 increased as more district sections were added to curbside collection, and not because of increasing participation. In 2018, expansion paused, and in early 2020, the program was suspended, returning in constrained form in 2021.

Figure 1. Tonnages of curbside organics collected through 2019 increased as more district sections were added to curbside collection, and not because of increasing participation or capture rates. In 2018, expansion paused. In early 2020, the program was suspended.

Yard Trimmings Collection In The 2000s

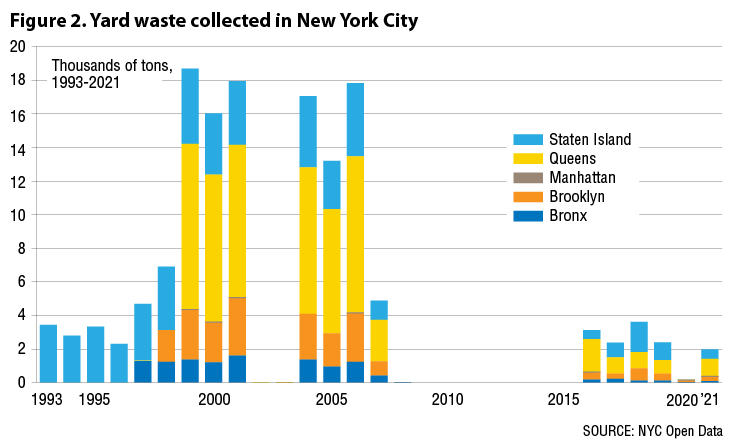

None of this is new. The city tried and abandoned curbside organics collection (including food scraps) in Park Slope in the late 1990s for precisely the reasons the current program flounders. But there have also been past successes to learn from. Twenty years before the curbside organics program’s zenith, DSNY was collecting over 18,000 tons of curbside compostables from residents with far fewer trucks, and better participation, than the present program shows. However, those organics were entirely yard trimmings (leaves in the fall, and briefly clippings in the spring). Tonnages fluctuated between 14,000 and 18,000 tons annually between 1999 and 2006, despite two gap years in service (Figure 2) .

Figure 2. Tonnages of curbside leaf and yard waste collected through 1997 increased as more district sections were added. By 1998, all leaf districts were covered. In 2007, clear bags were prohibited and paper leaf bags required. In early 2008, the program was suspended. In 2016 it resumed to serve leaf districts not covered under the curbside collection program, still with the paper bag mandate.

Rather than 52 weekly pickups, DSNY offered three seasonal collections in the fall in 34 out of 59 “leaf districts” outside Manhattan. By 1998, all leaf districts were covered. In 2007, tonnage abruptly dropped off because the rules changed. Rather than allowing clear plastic bags for yard trimmings, residents were required to buy and use paper lawn and leaf bags — a small, but impactful, hassle. The next year saw curbside yard trimmings collections cancelled, not starting up again until 2016 to serve leaf districts that had not yet been brought into the brown bin program. The mandate to use paper bags was still in place.

In 2007, NYC switches from allowing clear bags to requiring paper bags for fall leaves. Participation drops precipitously thereafter. Photo courtesy S. MacBride

The 2017 waste characterization study found that 60% of what was collected from brown bins in districts served by year-round organics pickup was, in fact, yard trimmings. Food scraps and compostable paper, in contrast, were 33% (7% was contamination). It doesn’t take a genius to guess why: compared to festering food and soggy paper towels, yard trimmings are cleaner and more familiar as something to separate. They get generated in batches as people rake, mow or clip — not in dribs and drabs along with other trash over each day. And while there are not as much yard trimmings in NYC as food scraps, there are still over 100,000 tons of leaves, brush, and grass in the one million tons of organics going to landfills.

Next Steps

It is essential that New York City make access to compostables collection equitable so that all districts are served. The patchwork expansion schedule that NYC followed with the brown bin program between 2014 and 2018 (when expansion “paused”) jumped all over the map, driven by varying states of readiness among DSNY district staff to begin collection. Neighborhoods most burdened by waste facilities were left out, confusing many. But a rush to make the program mandatory, which is currently advocated in the hopes of raising participation and diverting more from landfills, may well not achieve desired results.

”Mandatory” means enforced by citations, and fines. For a curbside organics program, this translates to ticketing generators who toss food waste in a bag of mixed trash, or who fail to set out a brown bin at all. Either prospect raises questions of fairness to residents, as well as safety for City enforcement workers, whose ranks are already stretched thin. Leaving aside the question of enforcement, there is the question of how to overcome participation hesitancy among apartment dwellers who won’t be fined. Today, superintendents, custodians, janitors and porters all over New York City have the thankless task of sorting paper, metal, glass and plastic for recycling when tenants fail to do so — which is often.

Responsibility for compliance with that mandatory law falls to these essential workers. Where incomes and rents are higher, and buildings better staffed, the recycling rate is also higher. Given that building workers are linchpins of sustainability in NYC, what would they have to take on for curbside food scraps collection to succeed? Can we imagine a porter fishing a turkey carcass out of the trash compactor to ensure the building avoids fines? Digging their hands into a pail of food scraps to retrieve an errant can? Will this result in a fair outcome for workers in buildings with fewer, less well-paid employees?

Banning Yard Trimmings Set Out As Refuse

Here is an alternative idea. Rather than rushing to bring back curbside organics including food scraps as mandatory and instating collection citywide, begin with a citywide ban on setting residential yard trimmings out as refuse, and offer a once or twice monthly collection in the spring, summer and fall (8 or 16 collections) throughout all districts except those in Manhattan. One of the deal breakers for the brown bin program was the immense cost of sending out trucks that drove long distances without filling up. That doesn’t happen with seasonal yard trimmings collections. Those efficiencies were proven back in the 2000s. In some areas, collections were boosted by running mechanical brooms to pick up concentrations of leaves, and dumping them in trucks on these efficient collection routes. Increasing yard trimmings collection frequency to once or twice a month except in the winter could extend that productivity and bring in greater tonnages.

A second benefit is clarity in enforcement. Every year in the fall, scores of black bags line streets in the Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens and Staten Island. You can tell they contain leaves — and only leaves — by kicking them. Make not using a black bag for yard trimmings the enforceable offense, and the contents will shift to brown bins, open pails, or paper lawn and leaf bags. Even better, make it easier to comply by allowing certified compostable clear plastic bags as an option — and work to get those bags in supermarkets and available online. A bonus of this suggestion is that multi-unit buildings without grounds will not be hurled post-pandemic into a mandatory program.

A third benefit may be to gradually build participation rates in organics recycling among residents of all types of housing. The need is dire to foster trust in the City’s approach to Zero Waste, so that a full, citywide curbside organics program can be reintroduced with a realistic expectation of success. The operative word is “may,” because no approach — especially making the program mandatory — is at all guaranteed. But reviving the enforced aspect of the program starting with material that lacks the “yuck factor,” and is straightforward for homeowners, custodians, and the DSNY sanitation workers to handle, can provide a base upon which to undo the inadequacies that led to big problems in the curbside program.

Ensuring continuity of service (no more “pauses”) and clarity in rules is essential as NYC tries, again, to figure out how to divert greenhouse gas-producing wastes from landfills, enrich soil, and support urban gardening. Here is where another plus comes in: the City already has its own capacity to accept, compost, and redistribute the extra tonnages that would be generated by banning yard trimmings from the trash. DSNY’s in-city composting facilities, which take mainly leaves, grass and prunings, earn a good return from private landscaper use already, and are the source of rich compost that gets trucked to nearby community gardens and farms within NYC.

The years 2013 to 2019 saw hundreds of thousands of plastic brown bins, and millions of kitchen containers, purchased and distributed; various approaches at community outreach tried; advertising campaigns in conventional and social media mounted; added routes, trucks, emissions, and costs; and relatively paltry tonnages yielded. These facts alone should suggest that a curbside program like before won’t magically begin to succeed just by bringing it back as mandatory. As activists, experts, and policymakers in NYC have been pointing out for decades, the City needs more, and different, public outreach and education, developed in two-way dialogue with residents of communities before bins roll in. On a true pilot basis, communications must be proven out with tonnage to see what actually makes a difference, before rushing headlong into expansion.

Further, community organizations who have, in contrast to the City, operated nimbly and successfully to run food scraps drop-offs, bike powered pickups, and local composting sites should be funded fully, and put front and center as beacons of what success actually looks like. Space precludes elaborating on the decades of work by grassroots organizations and thoughtful activists on this front. They have taken it upon themselves to bring NYC composting to where it is today. In an uncertain future, their innovations — and not mandatory uniform brown bin curbside collection — may be what is needed to divert food scraps to beneficial use at scales that diminish disposal. But if DSNY, with its trucks and facilities, is to get involved in collection, why not start over with yard trimmings?

Samantha MacBride, PhD, teaches urban environmentalism at Baruch College, and worked on DSNY’s curbside recycling and organics programs for over two decades. Peter McKeon retired from the New York City Department of Sanitation after a 32-year career. During his final 13 years, he served as Chief of Refuse and Recycling Collection.