Top: Biogas conditioning desulfurization unit. Photo courtesy of Paques Environmental Technologies, Inc.

Michael H. Levin

When BioCycle last reviewed the state of play in this area (May 26, 2020), the arc of the universe was bending toward justice. In a first-impression case involving three so-called “small refineries” exempted by U.S. EPA from their obligations to blend renewable fuels or acquire equivalent RINs from AD or other biofuel producers, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit unanimously invalidated EPA’s grant of those exemptions, then denied the refineries’ requests for rehearing (RFA v. EPA, 948 F.3d 1206 (Jan. 24, 2020); reh. den. April 7, 2020).

The Tenth Circuit held that refineries must have had continuous prior exemptions to qualify for a “disproportionate economic hardship extension” of those exemptions under the Renewable Fuel statutes; the only cognizable “hardship” was their cost of acquiring sufficient biofuel or RINs, not general economic conditions; and EPA’s waivers were arbitrary due to past Agency findings that refineries suffer no “hardship” because they generally pass RFS compliance costs to their customers. This decision threatened the viability of some 40 waiver requests then granted or pending before EPA for RFS compliance years 2016-2018, most or all of which had been filed after the refineries’ pertinent compliance years. It appeared to leave the Trump Administration few viable options to extend relief to its oil industry constituents while preserving the support of farm/biofuels interests enraged by waivers’ adverse impact on RINs revenues in the midst of a pandemic and disruptive Administration trade tariffs.

Then a series of head-snapping developments changed the picture again.

“Gap-Filling” Petitions

In an effort to end-run the Tenth Circuit’s ruling, refineries whose “hardship” exemptions had lapsed, been denied or never sought flooded EPA with requests seeking exemptions ‘back to the beginning” — in some cases back to RFS compliance year 2011 — in order to show “continuous exemptions” which then could be “extended.” Between March and July 2020, the number of exemption requests before EPA doubled from roughly 40 to over 80 due to these petitions, with more arriving through the fall. As even Trump EPA Administrator Wheeler was compelled to suggest, the “hardship” apparently claimed by these petitions was problematic — petitioning refineries already had complied with the RFS during the years for which they now sought an exemption.

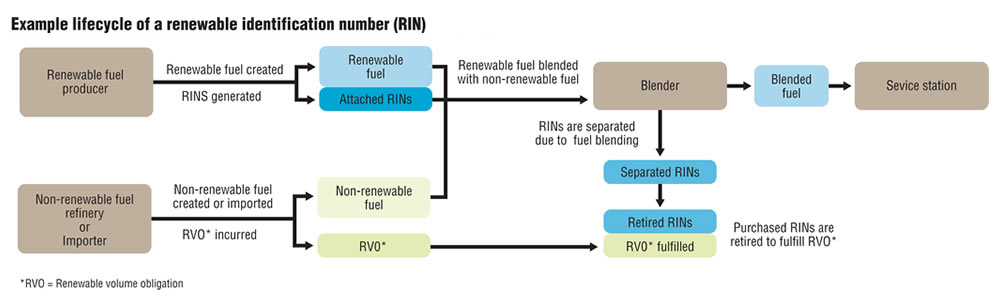

Source: “101 For RINs,” BioCycle 2017

It was not possible for affected biofuels interests to address the refineries’ justifications, because EPA continued to treat all aspects of exemption requests as confidential business information, disclosing only the numbers of waiver petitions pending, granted or denied. Indeed, one refinery (Kern Oil) went so far as to request anonymity in litigation it filed challenging a waiver determination — a request that court denied due to the “powerful presumption of openness in judicial proceedings,” having recently noted “a troubling picture of intentionally shrouded and hidden agency [hardship waivers] law that could have left those aggrieved by the agency’s actions without a viable avenue for judicial review.” (See In re Sealed Case (D.C. Circuit, Aug. 20, 2020); Advanced Biofuels Assn. v. EPA (D.C. Circuit, Nov. 12, 2019))

Worse yet, EPA seemed inclined to grant these petitions. Trial balloon press reports to that effect triggered furious competing letters to the White House from oil- and farm-state Senators, plus a flurry of less visible interventions. During summer 2020 the issue rose to the level of national politics, with President Trump declaring in Iowa that he would “speak to EPA myself about [waivers]” and Candidate Biden decrying the Administration’s “sell-out” of hard-hit farmers “by undercutting the [RFS] with the granting of waivers to Big Oil.”

By September, EPA faced nearly 100 pending waiver petitions, including 68 “gap-filling” requests. The president of ethanol giant Green Plains had announced a company-wide shift to production of non-price-volatile commodities, declaring, “I don’t ever want to be dependent on government policy again” and he had “lost faith the industry will get the support it needs from. . .the Trump Administration.”

EPA had bought time by serially referring the ‘gap fillers’ to the U.S. Department of Energy (DoE) for confidential “hardship” evaluation. On September 14, Wheeler personally denied the 54 “gap” petitions for which DoE had made recommendations. These included refinery requests for reconsideration of past denials; where DoE recommended no relief; and where DoE recommended 50% relief because it found “structural industry-wide hardship” though a refinery’s viability was not affected. Wheeler’s decision noted that it was questionable “whether a so-called ‘continuous exemption’ [even] is created by EPA granting a gap-filling petition many years after the small refinery has already complied with its RFS obligation for that year.” It found “these small refineries have not demonstrated disproportionate economic hardship in 2020 for RFS compliance years 2011 through 2018 when these refineries. . . successfully complied with those prior RFS obligations.” While it did not address the remaining 14 gap-fillers — or several dozen other pending hardship petitions — 2020 RINs prices promptly rose nearly 20% on this news.

Refinery Relief

Meanwhile the Trump campaign scrambled to please its bitterly divided adherents. It sought to allow sales of E-15 (15% ethanol, 85% gasoline) through E-10 (10% ethanol) pumps and remove E-10 storage tank and gas pump warnings that allegedly discouraged greater use of ethanol, though states controlled those labels. Citing the pandemic and “waiver uncertainty” that the Trump Administration largely had created, it proposed to delay small refiners’ 2020 RFS compliance dates and all refiners’ 2021 RFS compliance dates. President Trump promised a “new RVO package” that for the first time would increase required blend volumes to reflect every gallon exempted from RINs by hardship waivers — and “let EPA grant all the waivers it wants.” The White House floated the concept of Agricultural Department cash aid for aggrieved small refiners, though it was “unclear what statutory authority — or even financial account — the EPA might tap for that aid.”

Source: “101 For RINs,” BioCycle 2017

Cash aid was foreclosed when the House overwhelmingly passed a continuing resolution which not only barred such assistance, but required that all hardship petitions be submitted to EPA six months before the start of the pertinent RFS compliance year and be publicly disclosed (HR 4447, “RFS Integrity,” pp. 540-542, Oct. 19) (generally extending government funding through Dec. 11). In a chaotic run-up to election, the other Trump proposals went nowhere.

Neck-Bending Litigation

In 2019, EPA had inadvertently disclosed a decision memo by which the Agency for the first time issued 31 small-refinery waivers as a group rather than case-by-case, asserting it could grant 100% relief notwithstanding waiver lapses; agency precedent that both “structural hardship” and “impacts on plant viability” must be shown for a RINs exemption; and DoE findings that only partial relief based on “structural hardship” was warranted for some petitions. Biofuels groups promptly challenged that decision in the D.C. Circuit, then moved to suspend briefing until the then-pending Tenth Circuit RFA case was decided. In February 2020, after the Tenth Circuit’s decision, they revived their challenge to the 31 exemptions granted by EPA’s memo (RFA et al v. EPA, DC Circuit, No. 19-1220, biofuels opening brief filed Dec. 7, 2020).

In July 2020 two of the three small refineries whose hardship waivers were overturned by the Tenth Circuit had filed a certiorari petition asking the Supreme Court to review just that Circuit’s “extensions” holding. The odds against such review were daunting. The Court grants very few such petitions; both Tenth Circuit results were unanimous; there was no conflict with other federal appellate decisions; EPA (which had not asked the Tenth Circuit for rehearing) ultimately opposed review; and “the Supremes” could promote national uniformity simply by declining review. In addition, biofuels parties noted: (a) the “extensions” issue already was being litigated in the D.C. Circuit (usually a reason for the Supreme Court to deny immediate review); (b) that litigation was of “nationwide import” (an even stronger reason to avoid immediate review); and (c) reviewing just the “extension” point would not change the Tenth Circuit’s outcome because its reversal of the two refineries’ hardship exemptions also rested on independent grounds they had not challenged.

Beyond this, the D.C. Circuit, enforcing an opinion written by then-Judge (now Justice) Kavanaugh in a related RFS waiver matter, was about to order that EPA submit 60-day status reports showing how and when it would fix its still-uncorrected inclusion of imported ethanol when determining “adequate available domestic supply” for the 2016 RVOs. (See Americans for Clean Energy v. EPA, 864 F.3d 691 (July 28, 2017); Order, Jan. 27, 2021.) This order signaled that — at least according to the D.C. Circuit — waivers that undermine the RFS’ “market forcing intent” to encourage an expanding biofuels market are disfavored.

Nevertheless, on January 8, 2021 the Supreme Court cut across all this terrain — and granted review (HollyFrontier Cheyenne Refining LLC v RFA, No. 20-472). Since any four of the nine Justices can grant review and such orders contain no reasoning, it remains to be seen whether “cert” will be dismissed as improvidently granted, or a newly-conservative high Court will upset the hardship waivers applecart yet again. Unfortunately, as it did during its last days regarding immigration, health care and foreign policy, “Team Trump” may have left a land mine here: the inconsistencies it created could lead the Court to conclude that new EPA policies are owed no judicial deference.

Looking Ahead

President Biden has noted his dissatisfaction with “small refinery” exemptions that moved from less than seven waivers/year to an average of some 30/year during 2017-2020. He cannot have been pleased by the Trump EPA’s thumb-in-your-eye grant of three new exemptions — by themselves costing biofuels producers about $130 million at 50-cent RINs prices —on the eve of his inauguration. With some 60 waiver petitions still pending before EPA, the Biden Administration is positioned to avert similar outcomes. Even before it acts on those petitions, an early signal may come when the Biden Justice Department files its Supreme Court merits brief on behalf of the new EPA. That brief currently is due February 22. Many observers expect it will concede error and decline to defend the waivers.

Mike Levin, a BioCycle Contributing Editor, is managing member of the virtual law firm Michael H. Levin Law Group, PLLC (Washington DC) and a principal in NLGC LLC and Solar Shield LLC, which respectively focus on capital formation for renewable energy projects and optimization/development of roof-top PV systems in the District of Columbia. From 1979-1988 he was National Regulatory Reform Director at the U.S. EPA.