Top: Facility and compost utilization photos courtesy of McGill Environmental Systems, Atlas Organics and New Hanover County.

Emily Burnett, Colin Stifler and Sandy Skolochenko

Already famous for its beaches, barbecue, and college basketball, North Carolina may soon be known as the vanguard of the Southeast’s organics recycling industry. According to a study released by the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (NCDEQ) in January, the Tar Heel State is home to a growing number of composting, anaerobic digestion, and food recovery activities. The 2020 North Carolina Organics Recycling Study examines the flow of organic materials processed by permitted composting operations, the diverse products created from these materials, and the total capacity of existing organics recycling infrastructure. With nearly two million tons of available processing capacity, increasing amounts of organic feedstocks, and a growing interest in reducing wasted food, the state is poised to capitalize on the environmental and economic benefits of this blossoming waste diversion sector.

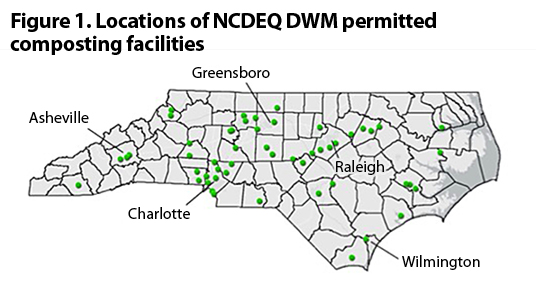

The data for the study was compiled from annual composting facility reports collected by NCDEQ’s Division of Waste Management’s (DWM) Solid Waste Section. Currently, 52 composting facilities are permitted by DWM and reported composting tonnages in Fiscal Year 2019-20. They consist of 24 private operations, 25 publicly‑operated sites, and three higher education institutions. Twenty-five facilities are permitted to receive only clean wood and yard trimmings and 27 are permitted to receive additional organic materials including food waste. However, only 15 facilities are actively accepting food waste based on data reported in FY 2019-20.

Figure 1 maps where the 52 facilities are located across North Carolina. Unless otherwise noted, the data referenced in this article does not include materials managed by composting operations under landfill permits or materials managed by facilities permitted under the Division of Water Resources (DWR). The food recovery section of the study utilizes data obtained from email and phone interviews with several nonprofit organizations and private businesses to quantify the food rescue and animal feeding diversion activities in the state.

North Carolina Composting Facilities

Figure 2 illustrates the increase in the number of composting facilities permitted by DWM since 2010. The decrease in permitted facilities from 58 in FY 2018-19 to 52 in FY 2019-20 is due to the establishment of new compost rules that went into effect in 2019, which exempt small facilities meeting certain conditions from permit requirements. Exempt facilities do not have to register with or report to the state per the new rules.

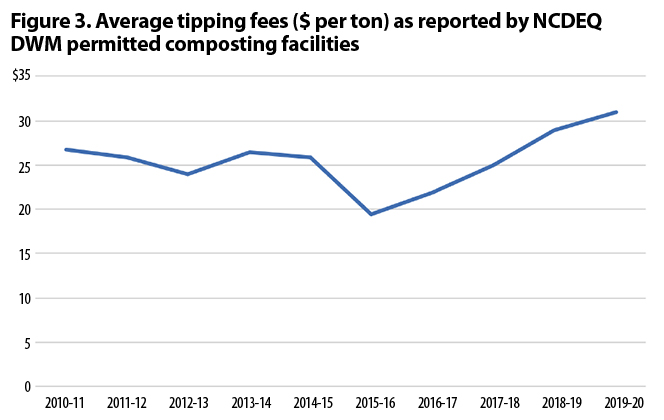

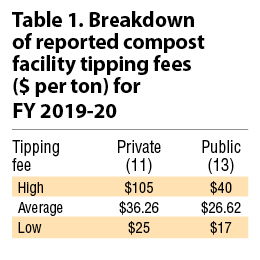

Figure 3 shows the average tipping fees charged by permitted composting facilities — an average of $26/ton for the past 10 years. In FY 2019-20, 24 commercial composting facilities reported tipping fees, with an average fee of $31/ton. For comparison, North Carolina’s average landfill disposal tipping fee for municipal solid waste was $44.06 in FY 2019-20. Table 1 has a breakdown of FY 2019-20 tipping fees charged by 11 privately and 13 publicly operated composting facilities.

Figure 3 shows the average tipping fees charged by permitted composting facilities — an average of $26/ton for the past 10 years. In FY 2019-20, 24 commercial composting facilities reported tipping fees, with an average fee of $31/ton. For comparison, North Carolina’s average landfill disposal tipping fee for municipal solid waste was $44.06 in FY 2019-20. Table 1 has a breakdown of FY 2019-20 tipping fees charged by 11 privately and 13 publicly operated composting facilities.

Organic Material Processing Capacity

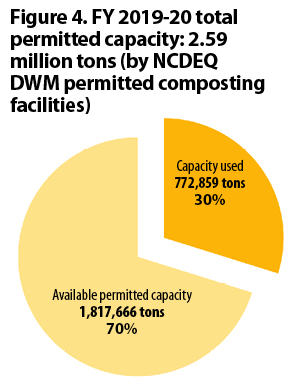

North Carolina is only using 30% of the available capacity to process organic material at composting facilities permitted by DWM (Figure 4). The state has enough remaining capacity to process an additional 1.82 million tons/year of organic material.

North Carolina is only using 30% of the available capacity to process organic material at composting facilities permitted by DWM (Figure 4). The state has enough remaining capacity to process an additional 1.82 million tons/year of organic material.

With this available permitted capacity, the state’s composting industry could process much of the excess food that is currently landfilled. Twelve (of the 27) composting operations that are permitted to accept food waste did not report receiving any in FY 2019-20. There are 25 composting operations permitted to accept yard trimmings and wood waste only that could pursue permit modifications to expand allowable feedstocks to include food waste. Additional small food waste composting operations would be needed in some areas of the state to decrease the distance between existing composting facilities and generators. The ability of composting facilities to handle excess food should not overshadow the ability to expand existing food rescue, animal feeding, and anaerobic digestion operations.

Material Inputs/Product Outputs

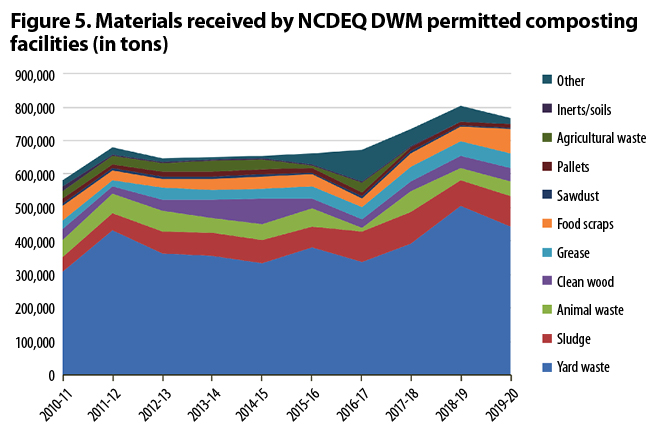

Since 2010, the total material received at permitted composting facilities has increased by 32%, or an average of 3.2% annually. The amount of yard trimmings received also increased by 44% since 2010, or a 4.4% average increase per year. On average, yard trimmings have constituted approximately 55% of the total materials received and made up 57% of composted materials during each of the last 10 fiscal years.

Figure 5 illustrates an evolution of reported materials received at all DWM composting facilities during the last 10 years. High carbon materials such as yard trimmings, clean wood, sawdust, and pallets make up approximately two-thirds of all received materials, of which yard trimmings are the most prevalent. High nitrogen materials (food waste, animal waste, sludge/biosolids, and agricultural waste and mortalities) make up 30%, while inerts, soils, and other organic materials account for roughly 5% on average.

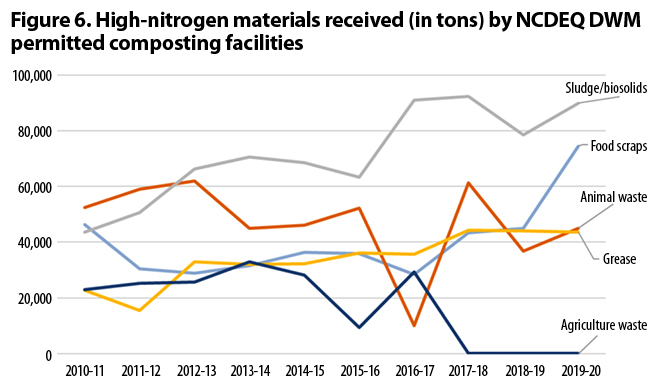

Figure 6 displays the trends specifically for high nitrogen content materials processed at composting facilities, such as sludge/biosolids, animal waste, food scraps, grease trap waste and agricultural waste. Upwards trends are seen for sludge/biosolids (106% increase since 2010, or 10.6% per year) and grease (93% increase since 2010, or 9.3% per year). Additionally, food scraps have increased 61% since 2010, possibly as a result of the increasing number of residential and commercial organics collection businesses throughout the state. The declining trend of animal waste feedstocks (14% decrease since 2010, or 1.4% per year) has been punctuated by several volatile years since 2015, while agricultural waste (99% decrease since 2010) has also declined considerably in the past five years.

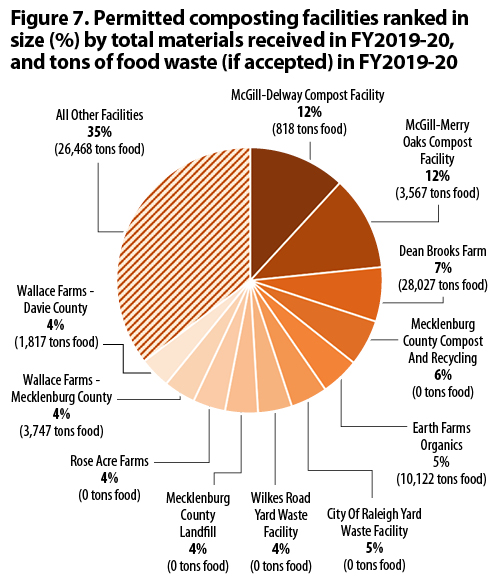

Figure 7 shows 11 facilities — 10 permitted by DWM and one by DWR (McGill-Delway) — that received the most material in FY 2019-20. The amount received is 65% of the total material received by all facilities (876,845 tons including McGill–Delway). DWR permits composting facilities when >50% of the material to be composted, not including bulking material, is animal manure or wastewater treatment sludge.

Figure 7 shows 11 facilities — 10 permitted by DWM and one by DWR (McGill-Delway) — that received the most material in FY 2019-20. The amount received is 65% of the total material received by all facilities (876,845 tons including McGill–Delway). DWR permits composting facilities when >50% of the material to be composted, not including bulking material, is animal manure or wastewater treatment sludge.

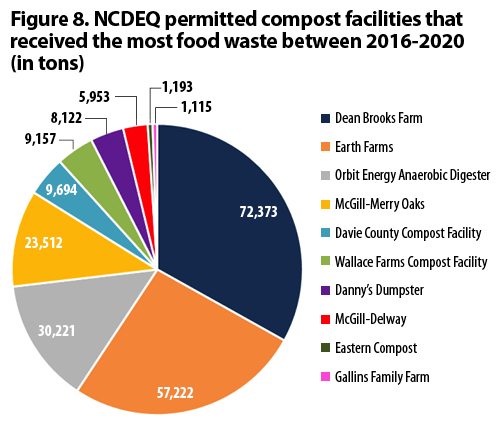

The 10 composting facilities that accepted more than 1,000 tons of food waste each year between 2016-2020 (Figure 8) processed 96% of all food waste received at permitted composting facilities, as compared to only 4% received by small facilities (defined as less than 1,000 tons/year).

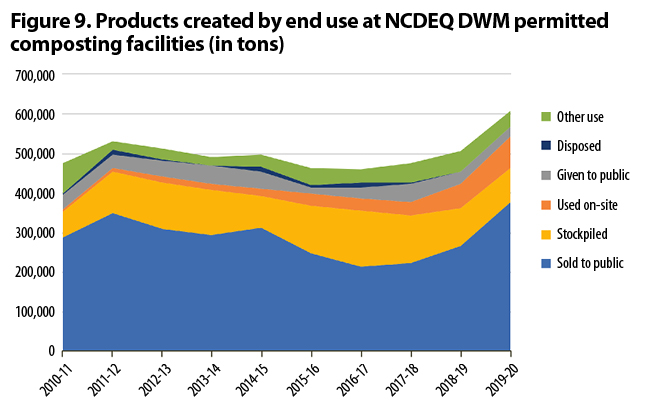

A breakdown of the end uses of the materials produced by composting facilities is highlighted in Figure 9. The data indicate that a steadily increasing amount of products were sold to the public and used onsite, while the “other uses” category (e.g., material sold as boiler fuel, used as landfill alternative daily cover, etc.) remained relatively stable. In contrast, the amount of stockpiled products and products given for free to the public has diminished gradually since 2018. The largest variations in annual usage during the last decade are products stockpiled and sold to the public; however, these two categories appear to have an inverse relationship — stockpiled tonnage tends to increase when fewer tons are sold to the public, and vice versa.

Organics Collection Access

North Carolina’s public composting sector continues to grow. While there are currently no publicly operated residential curbside food waste collection programs operating in North Carolina, several counties and cities have expanded food waste collection or partnered with private sector entities to offer a variety of food waste collection services.

Wake County has expanded its residential food waste collection program to four convenience centers in partnership with CompostNow. Another example is New Hanover County, which has a food waste drop-off program located at the county’s landfill. The county operates an in-vessel composting system and accepts food waste from the University of North Carolina at Wilmington, local restaurants, and residents. Henderson County, in partnership with Atlas Organics, has a food waste drop-off program located at its county convenience center. Henderson County is also in the process of constructing a county-owned-and-operated Type 3 composting facility. (Type 3 is a regulatory tier that allows composting facilities to accept manures and other agricultural waste, meat, postconsumer source separated food wastes, and other source separated specialty wastes that are low in physical contaminants but may have high levels of pathogens.) Orange County, in partnership with Brooks Compost, has continued its subsidized commercial food waste collection program as well as provides residents with a drop-off location at one of its convenience centers.

In the private sector, three food waste collection companies focus on both the residential and commercial sectors: CompostNow (Triangle and Asheville), Crown Town Compost (Charlotte) and Wilmington Compost Company (Wilmington). Two hauling companies operate statewide and focus exclusively on commercial food waste collection: Organix Recycling and Valley Proteins. Five composting facilities also offer food waste collection services: Brooks Compost (Chatham County), McGill Compost (Chatham and Sampson counties), Earth Farms Organics (Gaston County), Danny’s Dumpster (Buncombe County), and Gallins Family Farms (Davie County). Additionally, driven by businesses generating and requesting food waste collection services, at least two waste management companies partner with composting facilities to haul food waste: Republic Services and Waste Management.

Food Waste Recovery in North Carolina

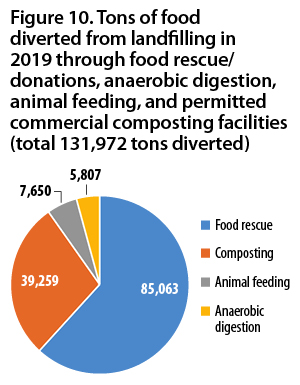

The department’s Division of Environmental Assistance and Customer Service published a food waste study in 2012 that estimated residential and commercial food waste totaled nearly 1.2 million tons each year, not including food losses during agricultural processing. The food recovered by food rescue organizations consists of perishable foods such as produce from farmer’s markets and grocery stores, and excess food from catered events and restaurants. Of the 1.2 million estimated tons of food waste generated annually, the four primary food waste diversion strategies — composting, food rescue, animal feeding, and anaerobic digestion — diverted approximately 132,000 tons (11%) of excess food from the landfill. This leaves 1.07 million tons of food still destined for landfill disposal.

Figure 10 breaks down the 131,972 tons of food waste diverted from landfills in 2019. Of this, 64% was diverted through food rescue efforts, 30% via composting, 6% by animal feeding, and 4% through anaerobic digestion.

Figure 10 breaks down the 131,972 tons of food waste diverted from landfills in 2019. Of this, 64% was diverted through food rescue efforts, 30% via composting, 6% by animal feeding, and 4% through anaerobic digestion.

Poised for Success

Collection remains the biggest challenge for North Carolina, especially for managing agricultural food losses as well as excess prepared food, food waste, and byproducts of food manufacturing. North Carolina has ample permitted capacity to move closer to reaching the Environmental Protection Agency’s, Food and Drug Administration’s, and U.S. Department of Agriculture’s joint goal of diverting 50% of national food waste from the landfill by 2030.

Moving the waste from generators to permitted facilities has its own challenges. The distance between the generators and processors of organic waste is a key economic consideration, as large distances can make collection prohibitively expensive. The creation of dense collection routes, ideally anchored by a few large generators, will be critical to improving system economics and reducing collection costs.

Despite the challenges of organic waste collection, the attention and momentum the sector is generating in North Carolina is leading to new opportunities, which indicate more growth is on the horizon. Many businesses, universities, and other organizations have begun adopting zero waste goals and are exploring alternatives to landfill disposal — even when it costs more to do so. Additionally, several states have already passed food waste policies and legislation while many more, including North Carolina, are considering following suit.

In short, with substantial recycling infrastructure and a steadily increasing supply of food waste feedstocks, North Carolina is positioned to capitalize on the growing demand for organics recycling for years to come. Read the complete 2020 North Carolina Organics Recycling Study.

Emily Burnett, Organics Recycling Specialist, Colin Stifler, Research Assistant, and Sandy Skolochenko, Community Development Specialist, are with the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality’s Division of Environmental Assistance and Customer Service (DEACS).