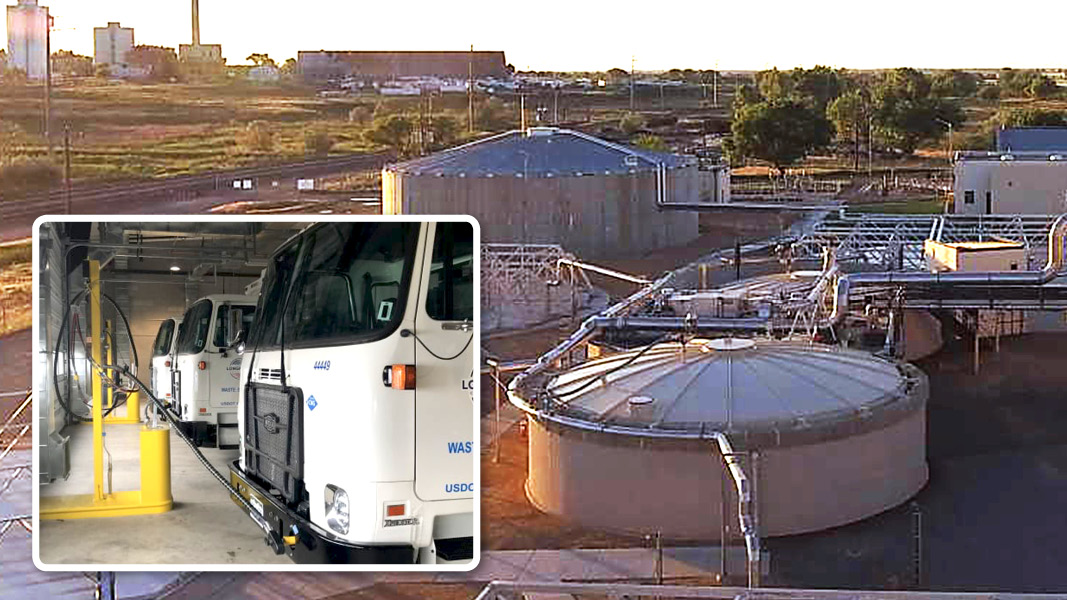

Top: The City of Longmont has five bays and 16 fueling positions for its current fleet of RNG-fueled collection vehicles. Photos courtesy of City of Longmont.

Michael H. Levin

Since the Trump Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) sharply expanded their post-2016 use, Small Refinery Exemptions (SREs) have undercut renewable fuel blending mandates by exempting over 4 billion gallons of motor fuels from acquiring RINs credits under the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS). In June 2021, the Supreme Court (reviewing a Tenth Circuit decision) ruled that EPA lacked “clear authority” under the RFS Program to limit that expansion by requiring “continuous” rather than “stand-alone” exemptions (HollyFrontierCheyenne v. EPA (114 S.Ct. 2172)).

BioCycle’s analysis of this ruling concluded it nevertheless left the Biden EPA numerous ways to deny such exemptions. This is partly because the Justices overturned only one of the three grounds for denial unanimously adopted by the Tenth Circuit, and partly because the Court majority found continuous and stand-alone approaches “equally plausible” on their face.

On December 7, 2021 the Biden EPA announced a 63-page “proposed adjudication” that would radically change the RINs playing field by denying not only all 65 pending SRE petitions, but virtually all future SRE requests. The announcement attracted little attention because it was buried in a large Renewable Volume Obligations (RVOs) notice prescribing the amounts of renewable fuel that refiners must blend into diesel fuels or gasoline during 2020-22. It’s worth drilling down on as the outcome directly impacts the renewable natural gas (RNG) marketplace.

Proposed Adjudication

- First, the proposal is subject “in all respects” to public comment — the first time in the notoriously secret SRE process that EPA has allowed such scrutiny. The comment period closed February 7, with all comments available in a public docket.

- Second, EPA chose not to take the Supreme Court head-on by affirming its prior stance that only small refiners with continuous past exemptions may receive an “extension of the exemption.” EPA could have done that, because in HollyFrontier it switched positions in the middle of litigation from the Trump stance that SREs may be granted “at any time.” Now EPA could offer an unambiguous “continuous exemption” RFS interpretation that was presumptively entitled to judicial deference. Instead, EPA apparently concluded it did not need to go so far to reach a more robust result. It took two steps (outlined below) to get there.

- EPA proposed to deny three SREs on grounds that while continuous past exemptions no longer might be required, to receive an “extension of the exemption” a small refiner must at least have been subject to the RFS Program’s initial pre-2013 blanket SRE from RINs compliance.

- Then EPA proposed to deny these and the other 62 pending petitions on much broader grounds. The only cognizable “disproportionate economic hardship (DEH),” EPA said (adopting one of the Tenth Circuit’s remaining unanimous holdings) is hardship caused solely by compliance with RINs obligations. And no such hardship was shown in any pending petitions — or generally can be shown — because economic theory plus collected market data demonstrate that in the “intensely competitive” fuels/RINs markets, to be able to sell product all players must either pass all their RINs purchase costs to consumers, or discount by the entire RINs price their internal costs of generating RINs by producing their own renewables.

For these reasons, EPA concluded, no small or other refiner is harmed (let alone harmed “disproportionately”), since for each of them the internal cost or external price of RINs is the same. Thus, EPA said, to show cognizable DEH a small refinery must “reconcile” claimed harm with the agency’s past findings (supplemented by demand/supply equations plus extensive current market research) that to compete, it must pass through all its direct or indirect RINs costs. Because RINs prices are national and even small refiners compete in interlaced markets, EPA indicated, a refiner’s geographic scope or other asserted constraints generally will make no difference.

EPA’s proposed approval criteria raise the question of whether they impermissibly write SREs out of the RFS. The agency presumably will reply in its “final adjudication” that narrow SRE windows, such as showing that a particular refiner’s market is not fully competitive, remain open. But future SRE requests would have a steep hill to climb.

Two related points should be mentioned. First, until 2020 EPA used the U.S. Department of Energy (DoE) two-part “scoring matrix” issued in 2011 to help determine whether DEH or separate “threatened economic viability” exist for small refiners. While EPA will “continue to consult with DoE,” the “proposed adjudication” discards that matrix as “outdated,” noting it did not reflect any RINs cost-passthroughs. Second, on December 8, 2021 the D.C. Circuit granted EPA’s request to remand for “new decisions” the ‘31 RV 2018’ SREs that the Trump EPA approved in one batch using the DoE matrix. Those SREs also appear doomed, if the “proposed adjudication” is adopted and upheld.

Mike Levin, a BioCycle Contributing Editor, is managing member of the virtual law firm Michael H. Levin Law Group, PLLC (Washington DC) and a principal in NLGC LLC and Solar Shield LLC, which respectively focus on capital formation for renewable energy projects and optimized development of rooftop PV systems in the District of Columbia. From 1979-1988 he was National Regulatory Reform Director at the U.S. EPA.