The Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community’s composting facility opened last fall, with capacity to process 400,000 cy/year of source separated organics.

Dan Emerson

BioCycle May 2012, Vol. 53, No. 5, p. 21

Food waste feedstocks include cucumbers from Gedney Pickle as well as grocery store and restaurant residuals.

Respect for the natural world and environmental stewardship is a tradition for Minnesota’s Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community (SMSC), making the tribe’s newest venture a perfect fit. The SMSC Organics Recycling Facility opened to the public last September, on tribal land, about 20 miles south of Minneapolis. “The Tribe had a need for disposal of its own waste someplace other than landfills,” says Stan Ellison, SMSC’s Land and Natural Resources Department Director.

SMSC operated a small-scale yard trimmings composting facility for almost a decade before opening the Organics Recycling Facility (ORF). Minnesota banned yard debris from landfills approximately three decades ago. “SMSC government operations have grown substantially since the Tribe’s founding in 1969 and particularly in the last decade and the Tribe needed to process yard waste and to produce compost for plantings,” says Ellison.

Adds SMSC Chairman Stanley R. Crooks: “The facility not only fulfills our ecological mission, it’s also helped improve relations with local governments in the area, who we have invited to use the facility free of charge.” All three neighboring cities of Prior Lake, Savage and Shakopee utilize the ORF to manage their municipal organics, already saving them tens of thousands of dollars in avoided disposal costs. Prior Lake and Savage offer citizens a drop-off day twice per month, with the cities hauling the material to the ORF.

Start-Up And Operations

The SMSC ORF has an annual design capacity of 400,000 cubic yards (cy), including 100,000 cy of food residuals. SMSC invested approximately $4.5 million, including construction and equipment. Staff developed a business plan that demonstrated a recouped investment in approximately five years from tipping fees (roughly 60 to 70 percent of revenues) and product sales (30 to 40 percent). The facility is currently operating at approximately 20 percent of its design capacity.

Filtered mud from potato washing is brought to the SMSC in a specially designed box. Material is scraped out with a Bobcat implement and used as a mineral component in some soil blends.

In addition to grass, leaves, brush and food residuals, the ORF processes livestock manure that is composted separately as SMSC intends to pursue organic certification for that product. Food waste feedstocks include cucumbers from Gedney Pickle and potato residuals from Northstar Potato, Wal-Mart grocery residuals and food waste from Chipotle restaurants. The ORF managers have been impressed by the cleanliness of the loads, in particular those from Wal-Mart and Chipotle that have an institutional commitment to accommodate composting. SMSC generates thousands of tons of food residuals each year and plans to divert them to the ORF.

Michael Whitt, Natural Resources Manager, and Russ Leistiko, Organics Management Supervisor, are in charge of day-to-day operations at the facility. Leistiko and Whitt established tipping fees that range from no charge in the case of clean logs and wood chips to $38/ton for source separated organics. Minnesota has a growing biomass industry that has resulted in high demand (and thus competition) for wood feedstocks. “We need the wood because it adds pore space within windrows that create favorable conditions for composting,” says Leistiko, a composter and former trash hauler with more than 30 years in the field. “We have low tip fees for most woody debris to ensure a good supply of wood. The ORF charges $28/ton for stumps that are usually difficult to get rid of because they are hard to grind.”

Site construction began on July 6, 2011 and exactly two months later, the ORF accepted its first load of source separated organics (SSO) from the Prior Lake-Savage School District. The school district has an ambitious program to collect lunch room materials including milk cartons separated by the students, cafeteria leftovers from cook staff, and even classroom paper products. “The program is young and has room for improvement but will be an example for other school districts when it is polished,” says Whitt.

The ORF is on 47-acres; 25-acres are fenced and include paved tipping and screening areas, composting pads, truck scale and a machine shop. The nearest neighbors are 1,600 feet away. The site is surrounded by planted native prairie, trees and shrubs, as well as agricultural land. The machine shop has a heated concrete floor that helps get diesel equipment through Minnesota winters.

After meeting PFRP, material is moved to a compacted soil pad where windrows are turned once a week. A lateral conveyor moves windrows down the pad during turning.

A Komptech Crambo 5000 with a mill that turns less than 40 rpm is used to grind and blend materials. Staff sort and manage incoming tipped materials into bunkers using two John Deere wheel loaders. Feedstocks are mixed using a recipe that blends carbon, nitrogen and moisture to create optimal composting conditions. Windrows are built on the asphalt pad, where material remains until the federal Part 503 PFRP standards are met (Process to Further Reduce Pathogens requires 15 consecutive days at 131°F with five turns during that period).

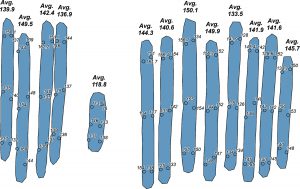

The ORF uses global positioning systems (GPS) and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to record daily temperatures and track the composting process. “We utilize 4-foot ReoTemp analog probes to obtain windrow temperatures,” explains Whitt. “The technician records six temperatures per windrow, three per side. We specified three points because this is the minimum amount for a good statistical sample for most applications. The technician re-cords each temperature location using a handheld Trimble GPS with submeter accuracy and incorporates the windrow number and temperature value using the GPS keypad. He performs this operation for every windrow and then downloads the data to a GIS when he returns to the office. The technician takes three oxygen readings at each immature windrow using a ReoTemp oxygen probe and also inputs these data into a GPS.” Figure 1 is an example of the type of graphic generated using the data collected.

Figure 1. Graphic display of windrow temperatures (6 points/pile and average) Figure 1. Graphic display of windrow temperatures (6 points/pile and average) using GPS and GIS tools

Windrows are moved to a compacted soil pad after PFRP has been met; at that point the piles are considered maturing compost. The ORF purchased a Komptech X67 Topturn to mix and aerate windrows that are 10 feet tall by 20 feet wide. A lateral conveyor connects to the X67, which picks up an entire windrow and moves it in the direction of the screening area. The entire composting process takes at least 12 weeks, after which the material is screened. During this phase, windrows are turned once per week.

Odor control is a principal focus at the site, and SMSC has a unique strategy. “The Land Department implements many prescribed fires as part of prairie management,” Whitt notes. “The conditions that are favorable for controlled burns, such as high dispersion and upper air movement, are the same conditions that are favorable to turn windrows.” Ellison adds that with community members as site neighbors, “we have a zero tolerance for malodors. As long as we keep turning the material, it stays aerobic and the aroma is not bad. It smells like silage.” Whenever a turn is scheduled, a tribal compliance officer drives around the site perimeter “to evaluate odors from the site.”

A star screen separates compost into three fractions. The 3/8-inch fraction is stored in 30-foot tall conical stockpiles (far left). The medium and coarse fractions are recycled back into the composting process.

Compost Markets

A Komptech L3 star screen is used to separate material into three fractions: fines screened to less than 3/8 inches, a medium fraction (approximately 6 inches or less) and a coarse fraction (>6-inches). Contaminants include plastics pulled off by the wind sifter. The medium and coarse fractions are recycled back to the beginning of the composting process. Fines (finished compost) are stockpiled for curing and future sale. They are placed into 30-foot tall conical stockpiles using a Kafka Radial Stacking Conveyor. The compost is tested by a US Composting Council-approved laboratory and sold by itself and in blends to the public. “SMSC is a big user of compost products,” says Ellison. “One project — an expansion of the dancing arena at the Wacipi, a Dakota name for Pow Wow — utilized 4,000 tons of an ORF compost blend.”

The SMSC used 4,000 tons of its compost blend to expand the dancing arena at the Wacipi, a Dakota name for Pow Wow. The site will be sodded prior to use.

SMSC sells compost in quantities varying from 5-gallon pails to more than 1,000 tons. Prices range from $18/ton for straight compost to $32/ton for specialty blends such as a rain garden blend. “Our ideal customers are landscaping contractors but we’re also arranging deliveries to home owners using local businesses including Turf Tamers, a business owned by a SMSC Tribal member,” Ellison adds. SMSC will pursue the USCC’s Seal of Testing Assurance certification in the near future.

Developers and especially highway engineers specify the compost to aid in erosion control and better growth and coverage of vegetation along construction projects. “Compost is naturally weed-free because of the prolonged high temperatures that kill weed seeds,” Ellison notes. “Roadside vegetation restoration is often more successful using compost and existing soils compared with importing black dirt that is heavier, more expensive to transport, and full of weed seeds.”

Ironing Out Wrinkles

The ORF has a staff of two part-time scale attendants, two equipment operators, and Leistiko, the site supervisor. Operations at the ORF may become 24 hours, five days a week in the near future. The major operational challenge so far was “getting the facility built,” says Ellison. “We’ve had a few minor equipment issues; it took a while to get some of the equipment ‘dialed in.’” One hassle is removing noncompostable materials such as plastic bottles and foil potato chip bags, which occasionally have to be hand-picked from the schools’ organic waste. Another hurdle relates to the Emerald Ash Borer, a nonnative, invasive beetle that

kills ash trees. Several Minnesota counties, including nearby Hennepin and Ramsey (where Minneapolis and St. Paul are located), have quarantines in place in order to control the spread of the ash borer. Some neighborhoods in Hennepin County mix organics with yard trimmings and wood waste, which can’t be removed from the county due to the quarantine.

The SMSC ORF staff is aggressively pursuing new feedstock contracts. Most food residuals in Minnesota are currently landfilled and generators are not accustomed to separating them for alternative disposal. This is due in part to the limited number of sites permitted to receive SSO. The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) is drafting rules to guide design of SSO composting facilities but the rules will not be in place until 2013. Up until this time, the few existing SSO facilities are either small demonstration sites or are built to municipal solid waste (MSW) processing standards.

Although the ORF is not technically subject to state regulation, the SMSC has expressed a willingness to meet Minnesota standards and to draft a Memorandum of Understanding with MPCA and US EPA to formalize the agreement. SMSC hosted one of two compost rule stakeholder meetings and has commented several times on the draft rules. “Trash haulers in the area are looking at starting SSO programs,” says Ellison, and “regulators are exploring methods to achieve greater diversion from landfills. Food residuals are the next big target because metal, plastic and paper recycling rates are already high in the Twin Cities metro area.”

The flow of food waste to the SMSC facility will increase in the next few months when it begins receiving organic material from nearby Mystic Lake Casino, which already provides ground-up discarded playing cards and other paper. SMSC will be adding another compactor to handle the additional material, and also plans to add waste from Little Six Casino just down the street as well as other facilities.

Dan Emerson is a Contributing Editor to BioCycle.