Top: Kitchens and retailers new to source separation may lack the knowledge and habits to properly separate organic from inorganic waste.

Melissa Hall, Ava Labuzetta and Chris Whitebell

The growing awareness of the impacts of wasted food on the environment and society is leading some U.S. states, like New York State, to put into place regulations to keep food scraps out of landfills. Under the rule, tackling food waste is shifting from a purely voluntary effort to a mandated one, bringing many more businesses and institutions into the organics hauling and recycling market.

While more businesses and institutions tackling food waste is without doubt a positive change, the boom may pose a more immediate challenge for haulers and recyclers. Kitchens and retailers who are new to source separation frequently lack the knowledge and habits to properly separate organic from inorganic waste. Writ large, this could drive a rapid rise in bin contamination — a potential nightmare for the organics industry, if left on its own.

Organics haulers and recyclers are all too familiar with the problems that inorganic materials like hairnets, produce stickers, and twist ties pose when they end up in their customers’ food scraps bins, such as lost time removing contaminants and costly equipment repairs. Bin contamination is a real problem that is likely to only grow as more large food scraps generators begin separating organics from other waste. What food scrap haulers and recyclers may not know, however, are the many potential reasons that contaminants are ending up in the waste stream or what they can do to help their food scraps generator customers keep it from happening.

Anticipating this scenario, experts from the New York State Pollution Prevention Institute (NYSP2I) at Rochester Institute for Technology are developing tools for businesses and institutional kitchens that are new to source separating their organic waste. These resources are designed to support retail and kitchen staff in order to shift long-held habits around how food scraps are handled. Most recently, NYSP2I created a troubleshooting guide that food retail and service managers can use to identify the causes of bin contamination and put in place practices to reduce it.

To create the guide, NYSP2I staff worked with food retailers, restaurants, and institutional kitchens to capture a range of root causes behind bin contamination. Many come down to common themes, such as confusion about how to separate organics from other waste and where to put it, a lack of buy-in and training at the employee level, or how things are organized in the workplace. In practice, the drivers of contamination take shape in ways that can be hard to see from outside the kitchen.

Talk Early And Often

The first step for haulers and organics recyclers when starting a collection program is to have a conversation with the generators to help them understand the issue, and to explain how contaminated bins negatively impact their operations. Very often, the generators are not even aware that their bins are contaminated.

Second, give the generators feedback in real-time whenever possible. Most likely, by the time haulers notice contamination, they’ve already commingled materials from various customers. This can make it hard to trace contamination back to a single pickup location. Providing immediate, specific comments is one of the best ways to create awareness and, ultimately, a change in behavior.

If you’re noticing recurring patterns or an increase in bin contamination, use the situation examples below — taken from the NYSP2I guide — to get a conversation going with the generators being serviced. Each example describes a type of contamination, the cause(s) behind it, and practical solutions for addressing it.

Example #1: Same contaminants frequently found

What you see: The same types of contaminants — such as plastic wrap, hairnets, or rubber bands — are frequently found in the generators’ food scrap bins.

What you might not see: Employees that are uninformed — or just uninspired — may not properly separate packaging from food items or be vigilant about keeping inorganic items from ending up in the bins.

Why it’s happening: Staff play a pivotal role in the success of a contamination education program, but this is sometimes overlooked at the start of a new program. The result is that employees may not receive consistent or regular training about the basics of a food scraps collection program, such as how to separate organics from other waste, the impacts of wasted food, or what happens to it when it is collected.

How to troubleshoot:

-

Show your customer the benefits of involving and empowering staff. Managers can also change work habits by regularly involving employees in discussions about their programs, including two-way dialogue. A “progress board” can be used to clearly display to everyone the goals, purpose, and current status of a food waste program. The board could also be used to provide feedback, incentivize, and celebrate victories large and small as goals are met or new records set. More generally, they can raise the importance of the program by routinely including it in conversation and staff huddles.

-

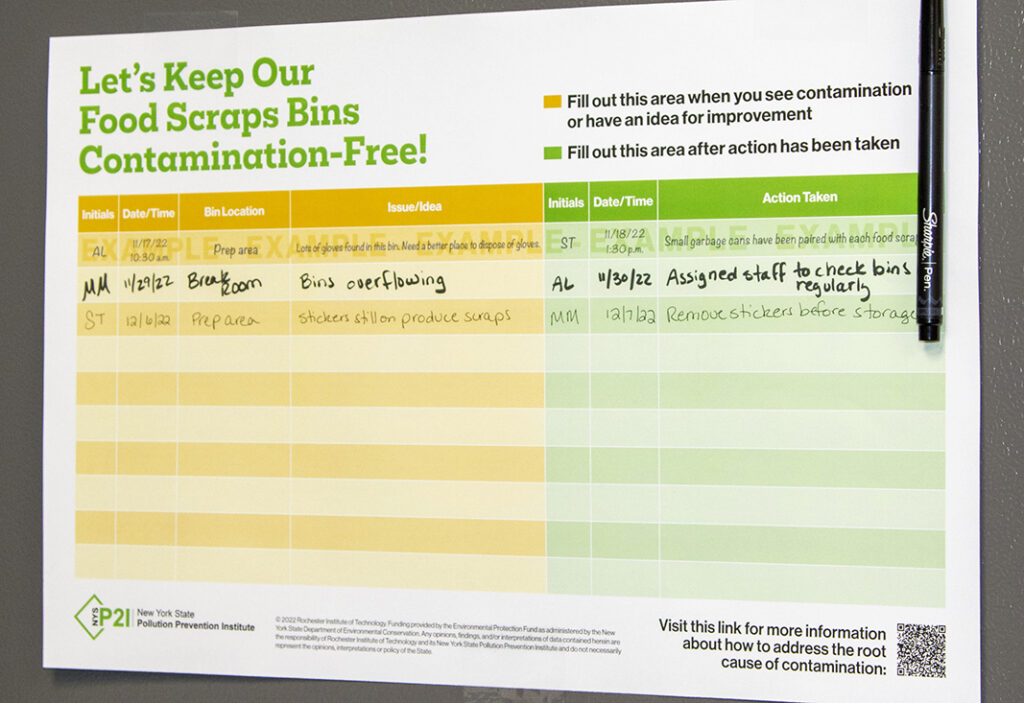

Record contamination events and suggest corrective action. The NYSP2I team created a poster alongside the guide that can be printed out and hung up nearby food scraps bins. Employees can record contamination events as they happen while also recording the reason and even suggesting a corrective action. The tool helps to build awareness of contamination and gives staff an active role in solving it. Moreover, it builds transparency: If the same contaminants are going into the bins over and over again, a pattern will soon become apparent.

-

Encourage your customer to educate their staff. A business or institution can be proactive about connecting the dots between a food scraps program and the impacts of wasted food on the environment, local communities, and the economy. This works best when it focuses on issues that genuinely resonate with most of its staff, customers, or both. From there, educational or inspirational messaging can be added to strategic locations within a facility, such as posters, brochures, or even digital content on a screen.

Example #2: Semi-frequent contamination, varying in types

What you see: Contamination of organics is semi-frequent, and the types of contaminants are inconsistent. For example, sometimes contaminants are mostly plastic utensils, but other times the bulk is made up of disposable sanitary gloves or miscellaneous packaging.

What you might not see: Your customer’s food scraps bins are located alongside those for recyclables and landfill waste. Employees and customers are left to do a lot of guesswork when they have to separate out waste materials between different bins.

Why it’s happening: Bins for food scraps aren’t clearly marked or easily distinguishable from receptacles for non-organic waste and recyclables — contamination is only a matter of time. Alternatively, customers or employees find the bins for recyclables and landfill waste full or overspilling, so hastily put non-organics into the food scraps bin.

Bins for food scraps should be clearly marked or easily distinguishable from receptacles for non-organic waste and recyclables.

How to troubleshoot:

- Have a look at your customer’s bin signage. The first step is to help your client learn who is getting confused and where it is happening. Kitchen staff? Management? Visitors or diners? From there, they can consider where clearer signage is needed and what knowledge gaps it should address. For example, if most of the contamination is occurring in the bins where kitchen employees are expected to source separate, then clearer, more focused bin signage directed at staff might alleviate confusion. Similarly, if the contaminants you see are all of the same type, such as plastic forks, then the issue may stem from how an area your customers use is organized.

- Schedule more bin swaps. If you discover that your customer is generating more waste than their bins can handle, offer to schedule more frequent pickups, provide them with additional bins, or connect them with a company that can help if the issue is an overflow of other types of waste.

Example #3: Food packaging in bins

What you see: A high proportion of the waste in your customers’ bins is either still packaged or the packaging has not been removed.

What you might not see: Kitchens or food prepping areas were already very busy places before staff were expected to collect food scraps. Overwhelmed and perhaps not adequately trained, they are unlikely to be judicious about separating out food from packaging or other inorganic material under the pressure of more immediate demands.

Why it’s happening: Very often companies that are new to collecting food scraps within their operations add source separating on top of existing tasks, rather than rethinking how staff handles waste from the bottom up. When this mentality is dominant, many opportunities are missed that could avoid extra steps that staff need to take to keep contaminants out of food scraps bins.

How to troubleshoot:

- See if your customers can give their staff more time to separate. Separating food from packaging takes time. When staff are rushed, they may unintentionally make mistakes. If management accounts for the additional time needed, staff are able to make the task of source separation a regular (and important) part of their duties rather than just an extra step.

- Suggest eliminating potential sources of contamination. Some potential sources that end up in food scraps bins are unlikely to go away, such as hairnets or gloves. However, other common items, like disposable condiment cups or straws, can either be removed altogether from use or substituted with compostable alternatives. Upgrading to bulk packaging, reusable ware, or acceptable compostable products can cut down on both source separation time and the likelihood of contamination.

- Suggest job rebalancing as a solution. A kitchen or retail manager can rethink staff responsibilities in order to make sure that separation tasks are not out-balancing existing duties. Ultimately, by making source separation an explicit responsibility, it raises the importance of a food scraps collection program as a whole.

Champion Good Ideas, Share Resources

In your work with multiple food scraps generators, you have a unique perspective. Keep your eyes open for organizations that have good practices in place and be proactive about sharing what they do with other customers. For example, if you see effective signage for explaining what can go into a food scraps bin at a kitchen you collect from, ask if you can have a copy of it to share with a customer you know might benefit from it.

The troubleshoots above — along with many more — can be found in NYSP2I’s full guide, Contamination in Food Scraps Bins: A troubleshooting guide for food retail and food service managers. Simple to use and free to download, the “do it yourself” resource outlines the root causes for bin contamination along with implementable solutions that managers can use to build more durable food scraps programs.

Melissa Hall manages NYSP2I’s food waste diversion program and Ava Labuzetta is a senior pollution prevention engineer at NYSP2I who focuses on food waste reduction and diversion. In addition to the bin contamination guide, Hall and Labuzetta have developed a number of tools and resources to help communities and businesses avoid or divert wasted food. Chris Whitebell is a senior writer and content strategist at Rochester Institute of Technology’s Golisano Institute for Sustainability, where NYSP2I is based.

© 2023 Rochester Institute of Technology. Funding provided by the Environmental Protection Fund as administered by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Any opinions, findings, and/or interpretations of data contained herein are the responsibility of Rochester Institute of Technology and its New York State Pollution Prevention Institute and do not necessarily represent the opinions, interpretations or policy of the State.