Rhodes Yepsen

WHILE collection of residential food waste is widespread in parts of Canada and many European countries, the U.S. has lagged behind. However, BioCycle’s nationwide survey this year uncovered more than 90 communities that are offering some type of food waste collection, more than double the number of communities identified in 2007, which reported 42 programs (see “Source Separated Residential Composting,” December 2007).

Some of this increase is due to more detailed tracking, asking counties to list the separate towns with residential organics collection (e.g. Swift County, Minnesota). But most is actual growth, with dozens of new programs popping up around the country. Temporary pilot programs are being set up to determine whether food waste collection is feasible for a particular city (e.g., State College, Pennsylvania; Hamilton, Massachusetts; Denver, Colorado). Longstanding regional programs have expanded services to new towns (e.g., Alameda County, California; King County, Washington). Two cities, San Francisco and Seattle, have even gone as far as to make residential organics collection mandatory.

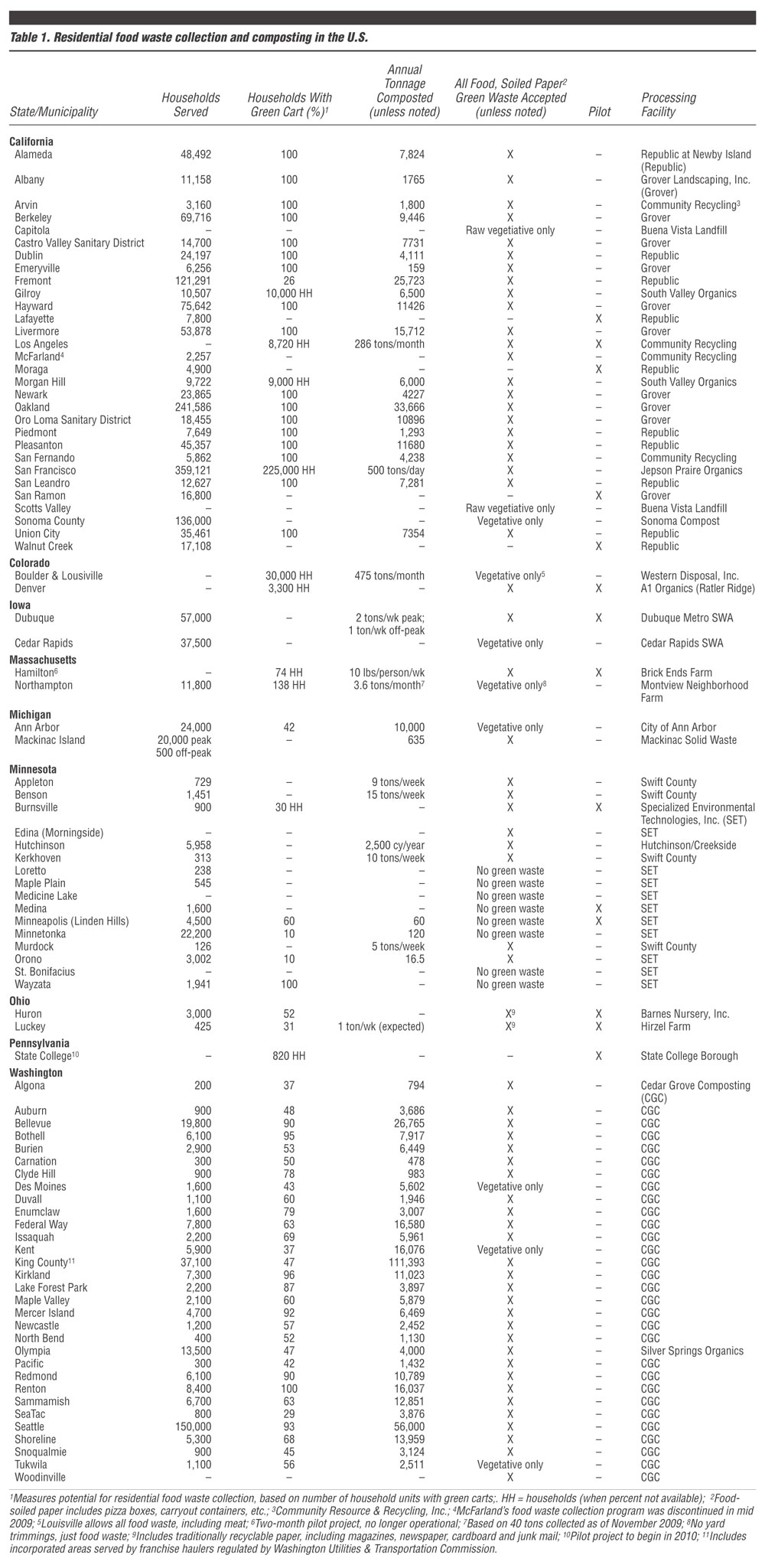

In past years, BioCycle surveys used the terminology “residential source separated organics (SSO),” defined as municipal programs targeting household organics beyond yard trimmings (e.g., food waste, food-soiled paper, etc.). However, there was debate in one community whether allowing residents to add only raw, preconsumer fruits and vegetables (primarily gleaned from gardens) in their yard trimmings carts should be considered. In another instance, a county differentiated between cocollecting food waste with yard trimmings in the same cart, versus collecting food waste and yard trimmings separately. In an attempt to avoid confusion, BioCycle editors decided to call the programs in this survey “residential food waste collection and composting programs.” Table 1 summarizes the data collected for 2009.

CALIFORNIA

CALIFORNIA

Alameda County: Several cities in Alameda County began offering food waste collection in 2002. These were funded by StopWaste.Org, a public agency comprised of Alameda County Waste Management Authority and Alameda County Source Reduction and Recycling Board. There are now 16 towns and cities in Alameda County with residential food waste collection programs. Food waste is cocollected with yard trimmings weekly in green carts, and taken to one of two composting facilities, Grover Landscaping, Inc. or Republic at Newby Island (formerly BFI). “Alameda County finally has 100 percent saturation, with organics collection offered to all 403,000 households,” says Brian Matthews, Senior Program Manager for StopWaste.Org. “We audit our cities twice a year, flipping cart lids and checking for food waste in both the green cart and trash bin, and participation rates have been increasing.”

This is in no small part because of StopWaste.Org’s extensive outreach and promotional campaigns. In the past few years, it has provided outreach materials in more languages. They feature thematic and seasonal outreach. For instance, a green cart says “¿Que te pasa Calabaza?” which translates to “What’s going on Pumpkin head?” in an effort to capture the rush of pumpkins after Halloween. There has also been a big push to compost more food-soiled paper, with promotions printed on pizza boxes and coffee cup sleeves, two easily targeted items.

Despite the auditing, participation rates are difficult to monitor, notes Mathews. “About 48 percent of households with green carts in Alameda County put food waste in, but it’s nearly impossible to determine why some families don’t use their green cart,” he says. “It could be that they were on vacation when the study was done, or that they forgot to put out the cart that week. We therefore conduct phone surveys about awareness of the food waste program, and ask reasons for not using the green cart. We are very pleased with the results of our most recent study, which shows trends of increased participation and awareness.”

Arvin, McFarland and San Fernando: The city of Arvin offers residential food waste cocollection with yard trimmings. About 1,800 tons/year of residential organics are collected, composted at Community Resource and Recycling, Inc.’s facility in Lamont. The city of McFarland had a similar SSO program, but it was discontinued six months ago.

In San Fernando, Crown Disposal (a sister company to Community Recycling) started collecting residential organics in 2002, along with trash and recyclables. Organics are collected weekly from all 5,862 single family households, and taken to Community Recycling’s facility in Lamont.

Los Angeles: The City of Los Angeles launched a residential food waste collection pilot program in September 2008. Food scraps and food soiled paper are placed into existing green yard trimmings bins. “The residents received an introductory letter and postcard notifying them of the program,” says Rowena Romano, Environmental Engineer Associate, City of Los Angeles Department of Public Works. “During roll-out, the City’s recycling ambassadors and maintenance laborers went door to door distributing 2-gallon kitchen pails and brochures to residents, as well as educating them on the program.”

The pilot is running in five neighborhoods, involving about 8,720 households. Participation was assessed by visually inspecting the green bin for food and food-soiled paper. Depending on the neighborhood, the green bin set out rate ranged from 32 to 5

8 percent, and food waste was included in 8 to 27 percent of the green bins.

All food wastes are accepted, cocollected weekly and taken to the city’s Central LA Recycling Transfer Station for hauling to Community Recycling’s composting facility in Lamont. Average monthly collection for the pilot is 286 tons (wet), about 2.7 percent of which is food or food-soiled paper (a weight-based waste characterization was conducted). “The city’s pilot program is ongoing and we’re currently planning to expand it,” concludes Romano.

Santa Cruz County, Scotts Valley and Capitola: Starting in the summer of 2008, residents in the unincorporated area of Santa Cruz County (not the city itself), and the towns of Scotts Valley and Capitola, can place raw fruits and vegetables in their green waste carts, serviced by GreenWaste Recovery. “The reason for the initiative was to get residents comfortable with the idea of putting food scraps in with yard trimmings,” says Melodye Serino, Zero Waste Analyst for Santa Cruz County. “We are in the process of applying for a permanent permit and hope to reconfigure space at the landfill area to increase composting and offer a full residential curbside collection program.” Residential organics are composted at the county’s Buena Vista landfill. “The county supplies the space and equipment and we contract services out to Vision Recycling.”

San Francisco: Mayor Gavin Newsome passed a mandatory source separation ordinance in June 2009, which came into effect in October. The first of its kind in the U.S., the ordinance requires residents and businesses to separate organics and recyclables from the garbage. “This ordinance essentially makes sure that no matter where you go in San Francisco, you’ll have opportunities to recycle and compost through the city’s curbside programs,” says Robert Reed, Public Relations Manager for Recology (formerly NorCal), which is contracted to haul the city’s wastes. “We already had a foothold and tremendous momentum. About half of the city’s properties had green bins, and all had blue bins. Since October we’ve been delivering between 100 to 150 green carts every day, up from about 25 to 50 before the ordinance.” Kitchen collectors are distributed with new green bins to encourage families to divert food waste, which is mixed in the yard trimmings bin.

San Francisco: Mayor Gavin Newsome passed a mandatory source separation ordinance in June 2009, which came into effect in October. The first of its kind in the U.S., the ordinance requires residents and businesses to separate organics and recyclables from the garbage. “This ordinance essentially makes sure that no matter where you go in San Francisco, you’ll have opportunities to recycle and compost through the city’s curbside programs,” says Robert Reed, Public Relations Manager for Recology (formerly NorCal), which is contracted to haul the city’s wastes. “We already had a foothold and tremendous momentum. About half of the city’s properties had green bins, and all had blue bins. Since October we’ve been delivering between 100 to 150 green carts every day, up from about 25 to 50 before the ordinance.” Kitchen collectors are distributed with new green bins to encourage families to divert food waste, which is mixed in the yard trimmings bin.

All told, about 225,000 households and over 4,000 businesses in the city now have green cart service. “About 46 percent of San Francisco’s 8,500 apartment buildings are now participating in organics collection,” says Reed. “That is more than double the number of apartment buildings a year ago. They were the city’s last frontier. We’ve also increased organics tonnage by 25 percent in the last year, averaging just under 500 tons/day. This has involved adding stops to routes, and we offer a lot of ‘inside service’ for apartment buildings.”

Promotional materials are continually updated. For example, the new lid sticker for the green carts uses only photos to indicate what to place inside, instead of words, to address the city’s multilingual population. “We replaced older stickers on all green carts in San Francisco with these new stickers,” says Reed. Collected organics are taken to Jepson Prairie Organics (which Recology owns and operates), located in Vacaville. Recology estimates that about 190,000 tons/year of food waste still could be diverted from the city’s waste stream for composting.

COLORADO

COLORADO

Boulder and Louisville: The city of Boulder recently regulated that haulers must offer organics collection, bundled at one rate with garbage and recyclables. Western Disposal, a hauling and composting company, services about 95 percent of the city’s residential clients, with 30,000 households in Boulder and nearby Louisville. “The new program came online for Boulder starting in August 2008, and was completed in January or February of 2009, with Louisville following in June,” says Bryce Isaacson, Vice President of Sales and Marketing for Western Disposal. “The landfill disposal fee in Colorado averages $13 to 14 per ton, so these are unique programs, because you are not saving by diverting. The government was needed to level the playing the field, requiring organics collection to be included with garbage service, at the same base price.” Boulder and Louisville have PAYT programs.

Boulder conducted residential organics pilot projects in 2005 and 2006 for about 2,500 households, during which Western Disposal delivered carts, kitchen collectors and two rolls of compostable bags. “The bags and kitchen pails really helped to facilitate the program, limiting flies and odors, but the cost of offering these materials citywide was too high,” he adds. The pilot programs were deemed successful, diverting 55 to 69 percent of residential waste.

In the current program, organics are collected every other week, alternating with recyclables. Due to the prevalence of bears in the nearby mountains, the program in Boulder doesn’t allow any meat or poultry, just fruits, vegetables, food-soiled paper and compostable products. Louisville is further from the mountains, and allows all food wastes. “On average, we collect 475 tons of organics per month, in addition to 517 tons per month from an organics drop off location, and 71 tons per month of commercial organics,” reports Isaacson. “Our residential organics tonnage will most likely increase as everyone comes on board. Just based on curbside collection of organics and recyclables, not including the drop-off, Boulder is now diverting over 50 percent.” The organics are hauled to Western Disposal’s composting facility, located within Boulder’s city limits.

Denver: A residential pilot project was launched in Denver in October 2008 to test the feasibility of curbside collection. Originally intended to run only through June 2009, the program was extended through March 2010. “We selected a few small areas of the city for the pilot project and asked homes to subscribe,” says Charlotte Pitt, Recycling Program Manager for Denver Solid Waste Management. “The neighborhoods are spotted throughout the city to ensure we’re gathering a representative sample. We only had funding for 3,300 households, giving out kitchen pails and 65-gallon curbside green bins. We received more subscription requests than we could offer.”

Denver: A residential pilot project was launched in Denver in October 2008 to test the feasibility of curbside collection. Originally intended to run only through June 2009, the program was extended through March 2010. “We selected a few small areas of the city for the pilot project and asked homes to subscribe,” says Charlotte Pitt, Recycling Program Manager for Denver Solid Waste Management. “The neighborhoods are spotted throughout the city to ensure we’re gathering a representative sample. We only had funding for 3,300 households, giving out kitchen pails and 65-gallon curbside green bins. We received more subscription requests than we could offer.”

All food wastes are allowed, including meat and food-soiled paper. Some participants were given two boxes of BioBags at the start of the program. Other BPI-certified compostable bags are also permitted. A1 Organics composts the collected organics at its Rattler Ridge facility in Keensburg, which is about 40 miles northeast of the city.

Collection is weekly during the growing season, and every other week during the winter. About 811 tons were collected from November 1, 2008 through June 30, 2009. “Our services are funded through the City’s general fund, which has taken a hit,” says Pitt. “We’re developing a plan that calls for citywide composting collection of food waste, yard trimmings and nonrecyclable paper, but at this time its up to the politicians to find the money for it.”

IOWA

Dubuque: The city of Dubuque’s residential organics collection program started as a two-year pilot in 2006, but is now permanent, offered to all 57,000 residents. During the pilot, 30 tons were collected the first year, and 35 tons the second year. The city provides 13-gallon wheeled Norseman containers with snap-locking lids, plus a 2-gallon kitchen collector. Food waste is collected weekly, commingled with yard trimmings in a solid waste packer truck, and delivered to the Dubuque Metropolitan Area Solid Waste Agency (DMASWA) facility. An estimated two tons/week are processed into compost, which is the current maximum of food scraps allowed under Iowa Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) rules. “We applied for a variance in January to expand to 6 tons/week, with the hopes to expand our food waste collection program to more businesses,” says Paul Schultz, Resource Management Coordinator for the city of Dubuque. “Although we offer organics collection to all 20,000 garbage customers, we are limited by the 2 tons rule. Eventually we will probably apply for an MSW composting facility permit, which would require about $250,000 for site improvements.”

Cedar Rapids: Cedar Rapids began allowing residents to place vegetative food waste in their yard trimmings carts in 1999. “This includes materials like coffee filters, vegetable peelings, fruit, etc., along with yard waste,” says Stacie Johnson, Education Coordinator for the Cedar Rapids-Lynn County Solid Waste Agency, which operates the city’s composting facility. “Organics are composted in windrows, with finished product given to residents for free. We also sell it to landscapers and use it for storm water management. Due to a major flood in 2008, about 1,2000 homes will be torn down – we will provide compost free of charge for seeding those plots.”

There are currently 38,500 households with garbage collection, 37,651 of which have 95-gallon green carts. “The difference in the total number of customers versus those with green carts is due to condominium complexes not wanting the carts,” reports Mark Jones, Superintendent of Cedar Rapids Solid Waste & Recycling Division. From July 2008 to June 2009 (the city’s fiscal year), 14,380 tons of curbside organics were collected. “We do not break out the food organics from the other yard waste, but I would say the food organics is still very low,” he adds.

MASSACHUSETTS

Hamilton: A residential food waste pilot project was conducted last winter in a neighborhood of Hamilton, Massachusetts. For about two months, all food wastes, including meat and dairy, were collected from 74 families. “Norseman provided us with curbside carts and kitchen collectors, New England Solid Waste collected the material, and Brick Ends Farm composted it,” says Gretel Clark, who helped organize the project. “On average, each household set out 10 lbs/week of food waste.”

The Hamilton Recycling Committee calculated that with 500 participants, weekly costs for organic waste collection would be $6.25/month. “We are collecting signatures from interested households, and currently have 300,” says Clark. The program, if instituted, would be offered to both the town of Hamilton (2,500 households) and the town Wenham (1,200 households).

Northampton: The Pedal People Cooperative, Inc. is a human-powered hauler offering garbage, recycling and organics collection in the towns of Northampton and Florence. In business since 2002, Pedal People uses bicycles with trailers to collect waste from businesses and residences, and offers rates that are competitive with conventional private haulers. Organics collection began in 2007. “We currently have 385 residential pickups, 128 of which have signed up for organics collection,” says Alex Jarretta, a founding member of the cooperative. “However, in the last three months 138 households have actually put out organics, event though some haven’t officially signed up for the service.”

Northampton: The Pedal People Cooperative, Inc. is a human-powered hauler offering garbage, recycling and organics collection in the towns of Northampton and Florence. In business since 2002, Pedal People uses bicycles with trailers to collect waste from businesses and residences, and offers rates that are competitive with conventional private haulers. Organics collection began in 2007. “We currently have 385 residential pickups, 128 of which have signed up for organics collection,” says Alex Jarretta, a founding member of the cooperative. “However, in the last three months 138 households have actually put out organics, event though some haven’t officially signed up for the service.”

Collected organics are biked to the Montview Neighborhood Farm, a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) operation located a few blocks from town. The three-acre farm is set on conservation land, and is also human-powered. “We have diverted 40 tons of organics this year alone, which is composted at Montview and applied to garden beds,” says Lisa DePiano of Pedal People.

MICHIGAN

Ann Arbor: The city of Ann Arbor rolled out food waste collection in April 2009, in an effort to pull more materials out of the waste stream. “We had positive experiences with our pilot projects, and thought it was timely to expand the service to our full population,” says Tom McMurtrie, with Ann Arbor Public Services. “Residents purchase a cart, and the service is paid for through taxes.” There are currently 10,000 households using green carts, out of 24,000 single-family units. Food waste is added to yard trimmings carts; tonnages are affected by seasonal changes.

About 10,000 tons of yard trimmings were collected in 2008 and processed at the city’s composting facility. A Morbark tub grinder is used for size reduction, and a Scarab for turning the windrows. “To promote the new service, we sent out an announcement in our WasteWatcher flyer to all households, and ran ads in the local newspaper,” says McMurtrie. “Only vegetative food waste is accepted at this point. We may expand to all food wastes in the future, but are trying to be cautious at first. We’re doing this project on a budget, using existing collection infrastructure, which has made the cost of implementation affordable.”

Mackinac Island: Mackinac Island started collecting source separated organics in 1992. The island is a historical community that prohibits motor vehicles, so horse-drawn trailers are used to collect wastes. There are just over 500 year-round residents, but during peak tourist season, about 15,000 visitors come to the island. “In the summer months, we collect organics 7 days per week, but this tails off to once a week in the winter months,” says Bruce Zimmerman, Director of Public Works on Mackinac Island. “We don’t use a scale for measuring the waste, but rather charge per bag, and extrapolate that number for estimated tonnage and cubic yard values.”

In 2008, about 635 tons of food waste were collected, as well as 583 tons of yard waste. Residents are charged $3/bag for garbage, but only $1.50/bag for organics. “At the composting facility, residential organics bags are opened and hand-sorted for contaminants,” says Paul Wandrie, who manages the facility. “The organics then travel via conveyor to a picking station, pass under a magnet for metal removal, and enter a shredder. We mix the shredded waste with manure, yard trimmings and commercial food waste using a front-end loader, and then compost it in aerated concrete bays.” All of the finished compost is used on the island.

MINNESOTA

In November, Minnesota finished a stakeholder process for a comprehensive waste management plan, and released a draft report of recommended strategies. “The group isn’t coming up with a total state plan, but rather is focusing on major populations centers, or ‘centroids,’ where the bulk of the waste is generated,” says Ginny Black with Minnesota Pollution Control Authority (MPCA). “According to the suggested plan, statewide organics goals will be set, with mandatory diversion. However, rural counties would not be required to recycle organics, even though about 41 of 87 counties are already involved with some level of organics recycling.”

Also under consideration is a revision of the state’s composting rules to allow for a third category, to increase food waste processing capacity. It would be less stringent than a solid waste permit, but more controlled than a yard trimmings site permit. “If a statewide goal is established for organics diversion, this will create more demand for food waste composting facilities,” says Black. The revised rule would most likely focus on compost pad surface type, finding an intermediate level between requiring a landfill lining (solid waste permit) and almost no surface requirement at all (yard trimmings composting site). The rules will probably also involve formalized BMPs, such as minimum buffer zones.

Dakota County: The city of Burnsville rolled out a food waste collection pilot program in 2003, which continued to operate until this year. The program initially had 900 households in the North River Hills housing development, with collected waste sent to Specialized Environmental Technologies, Inc. (SET, formerly Resource Recovery Technologies) for composting. However, participation has dwindled to about 20 or 30 households. Burnsville recently announced that it will stop the program.

Hennepin County: Several communities in Hennepin County have residential food waste collection. The city of Wayzata started its program in 2005, whereas Minnetonka, Orono and Loretto came online in 2007. “There are also pilot projects for collecting food waste in Linden Hills, a neighborhood in Minneapolis, and in Medina and Medicine Lake,” says John Jaimez, with Hennepin County Department of Environmental Services. “All of Hennepin’s programs collect food waste separately from yard trimmings. Although this may reduce hauling efficiency, compared to cocollection, there are several advantages to our system: the ability to accurately measure food waste, to meet specific diversion targets; residents see the existing green cart as primarily for yard wastes, and secondarily for food wastes, which limits use for food waste; and, compost facilities like the clean food waste streams, which are easy to mix for the right C:N ratio.”

Hennepin County: Several communities in Hennepin County have residential food waste collection. The city of Wayzata started its program in 2005, whereas Minnetonka, Orono and Loretto came online in 2007. “There are also pilot projects for collecting food waste in Linden Hills, a neighborhood in Minneapolis, and in Medina and Medicine Lake,” says John Jaimez, with Hennepin County Department of Environmental Services. “All of Hennepin’s programs collect food waste separately from yard trimmings. Although this may reduce hauling efficiency, compared to cocollection, there are several advantages to our system: the ability to accurately measure food waste, to meet specific diversion targets; residents see the existing green cart as primarily for yard wastes, and secondarily for food wastes, which limits use for food waste; and, compost facilities like the clean food waste streams, which are easy to mix for the right C:N ratio.”

Most of Hennepin County’s organics are taken to SET, which is located in Empire. “SET took over the facility from Resource Recovery Technologies in October 2008, but we’ve actually been the operator this facility since 2000,” says Kevin Tritz of SET. Since the Governor signed into law a ban on the use of plastic bags for organics collection (effective January 1, 2010), feedstocks have been getting cleaner. “The food waste from programs in Hennepin County already has noticeably less contamination,” notes Tritz. “Our finished compost has subsequently improved, and is selling much better than before. Our average monthly throughput of SSO for January through October, 2009 was 439.31 tons, which is a combination of commercial and residential, since it mostly comes in on transfer trailers. This is an increase from 2008, when the average was 137.57 tons/month. This is primarily because the other locations where Hennepin County was sending its organics either closed or were shut down.”

One of the places that Hennepin had been sending organics to is the University of Minnesota’s Landscape Arboretum, a demonstration composting project in Carver County. Due to odors the facility closed this year, with plans to reopen at a different location at the arboretum. “The pilot project started in 2007 to demonstrate cocolleciton of food waste and yard trimmings, composted at a yard trimmings site,” says Marcus Zbinden, Environmental Specialist with Carver County. “However, it became overwhelmed with larger quantities of food waste, processing them in nonaerated static piles that reached 18 feet. The buffer was only about 250 feet, with houses across the road. Another development is that Waste Management, our original partner, has discontinued residential organics collection services.”

Hutchinson: The city of Hutchinson continues to collect about 2,500 cubic yards/year of residential organics, composted at Creekside Organics Materials Processing Facility, which the city operates. “We still provide compostable bags at no cost to residents, and are currently using Husky EcoGuard and BagToNature,” says Doug Johnson, Compost Site Coordinator for Creekside. “We have 98 percent participation, and if we didn’t provide bags, people wouldn’t participate as much. There would also be more contamination, and the cost to dispose of black plastic bags would be immense.”

Creekside mixes the residential SSO with yard trimmings and some commercial food waste, composted in Engineered Compost Systems (ECS) in-vessel containers. It has expanded its bagging line from 1.2 million bags/year to almost 2 million.

Swift County: Swift County started its residential SSO program in 2000. About 3,800 households are participating in programs in eight cities: Kerkhoven, Murdock, De Graff, Benson, Clontarf, Danvers, Holloway and Appleton, and about 300 households in other rural communities. “About 62 to 68 percent of households currently subscribe, with the best probably being the city of Kerkhoven, with rates up to 80 percent,” says Scott Collins, Solid Waste Officer for Swift County Environmental Services. “We are only able to separate out tonnage data for four of the cities, but all told, our facility receives 20 tons/day, which is small enough that we can baby our compost process, making it very hands on at every step.”

OHIO

OHIO

Huron: The City of Huron offers seasonal yard trimmings collection by subscription ($8/month), running from April to January. There are 1,579 subscribers, or more than half of the city’s 3,000 households. This year, Barnes Nursery worked with Huron to include food waste in the program, and extend collection year round. “This wasn’t hard work, because the program was already there; we just added food waste and introduced some good educational programs,” says Sharon Barnes of Barnes Nursery, Inc., which composts the organics at its nearby facility. “We were already taking the yard trimmings, so it was a natural fit, and the residents with yard trimmings were already committed to recycling, willing to pay extra for it.”

The program is far from formal, with no funds for green bins. “We get the job done, but it doesn’t always look pretty,” says Barnes. However, the city is considering an all-inclusive program where everyone would have the service at one price. “To encourage more participation, we offered a drastically reduced tip fee to Huron if all residents were signed on,” she continues. “This is appealing to the city, the haulers, and ultimately the residents, all who will save money while lightening their environmental footprints.”

Luckey: The village of Luckey began a residential food waste program in October. In fact, the faltering recycling program was replaced by organics collection. Only 700 to 1,000 pounds of traditional recyclables were being collected each week, which wasn’t enough to pay for hauling costs. NAT Transportation, which collects trash at 350 households, repurposed the recycling bins for organics. Recycling bins are now being used for food waste (including meat and dairy), yard trimmings, and traditionally recyclable paper like newspaper, magazines, cardboard and junk mail. About 130 households have signed on, with organics sent for composting at Hirzel Farms, which was already taking the village’s yard trimmings. Mick Torok of NAT Transportation anticipates that they’ll be able to collect 2,000 pounds a week. A drop-off location for traditional recyclables has been set up for residents.

“Interest in food waste composting has grown a lot in Ohio, more than we expected,” says Angel Arroyo-Rodriguez, Environmental Specialist for Ohio EPA. “For instance, the town of Bexley, near Columbus, is interested in launching residential food waste collection. Yard trimmings are already collected in Bexley, taken to a Class II compost facility that accepts food waste from a Kroger supermarket, so why not add residential food scraps?”

PENNSYLVANIA

State College: The city of State College in central Pennsylvania, home to Penn State University, will be launching a residential food waste pilot program next year in two neighborhoods, with a total of approximately 820 households. “The pilot will go at least 18 months,” says Joanne Shafer, Deputy Director/Recycling Coordinator for Centre County Solid Waste Authority. “We will then determine from the testing and evaluation part of the pilot when and how to roll out fully blown residential collection.”

A 2003 Waste Composition Study gathered information from neighborhoods across the city. “We have also been getting collection data from the refuse routes in these particular neighborhoods since Sept 1, 2009 to get baseline data,” notes Shafer. State College Borough Public Works will collect the organics and compost them with yard trimmings at the Borough’s facility.

WASHINGTON

King County: King County (KC) includes 37 cities, with a population of 1.8 million. Seattle is located in KC, but opted out of the county’s solid waste programs and is listed separately. Residential organics are collected in 28 cities in KC, all of which are sent to Cedar Grove Composting. KC first launched a residential organics collection pilot project in 2001, and offered a full-scale program in 2004.

A recent organics characterization study revealed several key findings: about two-thirds of households in KC subscribe to organic service; about 50 percent of set outs contain food scraps; food scraps and compostable paper capture rate for participants is approximately 77 percent; the average participant includes about 35 pounds of food was and soiled-paper each month; and, about 88 percent of all curbside organic materials is yard trimmings.

Olympia: In July 2008, the city of Olympia added food waste to its existing residential yard trimmings green cart service. This boosted curbside organics tonnages by about 400 tons/year to reach 4,000 tons/year. About 6,800 households out of 13,500 are currently subscribed, choosing either a 95-gallon or 35-gallon green cart (same cost). New customers also receive a Norseman kitchen pail. Collection is biweekly, and includes all food waste and food-soiled paper, mixed in with yard trimmings.

The organics are sent to Silver Springs Organics in Rainier, Washington, where they are composted using Engineered Compost Systems (ECS) aerated static piles. Silver Springs provides a list of approved compostable plastics. During the initial roll-out, Olympia held neighborhood meetings, sent out flyers in the mail, used internet promotions, advertised on local public TV and in newspapers, etc.

“The hardest part is trying to get a handle on participation,” says Ron Jones, Senior Program Specialist for Olympia Public Works. “We hired a professional firm to help us conduct a telephone survey to learn more about customer behavior – both those who subscribe, and those who do not.”

Seattle: Earlier this year, Seattle’s mandatory food waste participation program came into effect. “It directs single-family households to participate in either curbside food and yard waste collection or backyard composting,” says Brett Stav, Senior Planning and Development Specialist for Seattle Public Utilities (SPU). “Households are exempted from mandatory green cart service if they state they compost their food waste at home. The city has 150,000 households, 140,000 of which now participate in curbside food and yard waste collection.” In 2007, BioCycle reported that 103,000 households had signed up for service.

Seattle: Earlier this year, Seattle’s mandatory food waste participation program came into effect. “It directs single-family households to participate in either curbside food and yard waste collection or backyard composting,” says Brett Stav, Senior Planning and Development Specialist for Seattle Public Utilities (SPU). “Households are exempted from mandatory green cart service if they state they compost their food waste at home. The city has 150,000 households, 140,000 of which now participate in curbside food and yard waste collection.” In 2007, BioCycle reported that 103,000 households had signed up for service.

“So far, curbside organics collection is up 30 percent this year over last year,” explains Stav. “Last year, residents diverted 56,000 tons. We’re also seeing approximately 6 percent of our customers switching to smaller garbage cans.” Starting March 30, 2009, SPU began offering three sizes of green cart, adding the smaller Norseman 13-gallon ($3.60/month) and 32-gallon ($5.40/month) to its standard offering of 96-gallon ($6.90/month).

The city also switched to weekly organics collection from biweekly, and began allowing all food scraps, including meat and dairy (vegetative food waste has been allowed since 2005). “Smelly, messy carts have been an obstacle to curbside participation, and weekly collection has helped knock that barrier down,” he continues. “Seattle will soon undertake a study on the effectiveness of every other week trash collection.” Collected organics are taken to Cedar Grove Composting.

STRICTLY DROP-OFF

In the process of surveying states and counties about residential food waste collection programs, BioCycle came across many instances of drop-off locations that are accepting residential food waste. Although this is not a new category it is an area that deserves more attention, as many rural communities are adopting it as a solution for capturing residential food waste.

In some cases, the communities already have commercial food waste collection, but cannot justify a residential route, such as at the Intervale facility in Burlington, Vermont, which is operated by Chittenden Solid Waste District. In 2008, two residential food waste drop off sites opened in Cambridge, Massachusetts, one at a community recycling center, and the other at a Whole Foods Market. In New Hampshire, municipal yard trimmings sites in Peterborough and Keene are allowing small amounts of residential food waste, such as pumpkins and garden scraps. Table 2 is a partial listing of drop-off programs that allow residential food waste, as BioCycle has just started to collect information on these programs.

Duluth, Minnesota: Western Lake Superior Sanitary District (WLSD), based in Duluth, covers a 530 square mile area in northeastern Minnesota. WLSD provides curbside collection of yard trimmings, and has six residential food waste drop-off sites at local businesses, the WLSD recycling facility and the WLSD composting facility. “The most recently added location is at Chester Creek Café, in the University district of Duluth, which is about 98 percent residential,” says Susan Darley-Hill, Environmental Program Coordinator for WLSD. “About 40 tons/month of organics are delivered to our composting facility, but the same hauler services commercial food waste accounts and the drop-off bins, so it is difficult to monitor residential diversion tonnages. However, we know the volume has increased, based on the number of trips required, and the new drop-off site.”

Duluth, Minnesota: Western Lake Superior Sanitary District (WLSD), based in Duluth, covers a 530 square mile area in northeastern Minnesota. WLSD provides curbside collection of yard trimmings, and has six residential food waste drop-off sites at local businesses, the WLSD recycling facility and the WLSD composting facility. “The most recently added location is at Chester Creek Café, in the University district of Duluth, which is about 98 percent residential,” says Susan Darley-Hill, Environmental Program Coordinator for WLSD. “About 40 tons/month of organics are delivered to our composting facility, but the same hauler services commercial food waste accounts and the drop-off bins, so it is difficult to monitor residential diversion tonnages. However, we know the volume has increased, based on the number of trips required, and the new drop-off site.”

WLSD purchases compostable bags and provides them free to residents. “This helps us reduce contamination in the compost, but it also keeps the host sites for drop-off bins cleaner,” says Darley-Hill. “Cases of the compostable bags are given to the host business, and when residents drop off a bag of food waste, they go into the business or recycling center and ask for another.” Several brands are used, but currently they offer Cortec and BagToNature.

The drop sites service the greater Duluth area, which includes the city of Duluth plus five rural townships and two suburban communities, for a total of 43,895 households. Residents in the neighboring city of Superior, Wisconsin also use the drop-off sites, adding another 11,515 households.

New York, New York: The Lower East Ecology Center (LEEC) started a community compost program in 1990, accepting residential food waste at its community garden on East 7th Street. Since 1994, LEEC has also collected residential food waste at the Union Square Greenmarket four days a week. In 2009, LEEC collected 312 tons of vegetative food waste at the two locations. These organics are transported to East River Park and processed using an in-vessel composting system. Finished compost is sold at the Greenmarket, either as compost or as part of a potting soil mix.

Brattleboro, Vermont: Brattleboro’s commercial organics program began five years ago, and expanded to include residential food waste in May 2009. “We decided to place a container on site at our MRF to offer the opportunity to residents,” says Cindy Sterling of Windham Solid Waste Municipal District (WSWMD).

“Participation has noticeably increased this winter, as I think many of the backyard composters are enjoying this alternative for the colder months. And we are getting people that do not have the space for a backyard bin.”

Called “Project COW,” or Commercial Organic Waste composting, the drop-off site was intended to be a pilot project ending in October, but the Board of Supervisors voted to keep it going until December 31, 2009. “Right now the program is being subsidized by the WSWMD,” says Sterling. “It was paid for by a USDA grant through October 2009, so now the Board needs to decide if they want to keep operating it, subsidize it or charge a minimal user fee.”

Service is available to all WSWMD residents, which includes 19 towns, or about 37,000 people. One 4 cubic yard dumpster is used, collected monthly. All food wastes are allowed (including meat and dairy), as well as compostable products. “We don’t presently invite businesses to take part in this program, only residents,” explains Sterling. However, the Vernon Elementary School now hosts a second drop-off site for residential food waste. Organics are currently hauled to Martin’s Farm in Greenfield, Massachusetts, but WSWMD is looking to compost the material locally.