Sophia Jones

To successfully reduce, divert and manage the organics and recycling streams, one mechanism with a proven track record of raising funds for diversion and composting infrastructure is the establishment of a per-ton surcharge on waste landfilled or incinerated. A waste disposal surcharge is typically a fee added to the per-ton tipping fees charged at waste disposal sites. Some state and local governments levy these surcharges to solely support agency costs for solid waste facility licensing, permitting, registration or operation. Others use these per-ton surcharges to also support the establishment, expansion, and maintenance of recycling and composting projects.

The Institute for Local Self-Reliance’s (ILSR) Composting for Community Initiative analyzed 10 examples of existing regulations that allocate revenue from waste disposal surcharges to fund waste diversion, reuse, recycling, composting, and other sustainability initiatives. The findings of the analysis were published in an online article in February, and provide best practices and possible solutions to roadblocks. The analysis may help to guide development of new legislation to fund composting and divert waste. This article is excerpted from the full report.

Surcharge Mechanisms

The Foodbank, Inc. in Dayton received a grant from the Ohio EPA to help purchase an in-vessel composter to process food waste. Photo courtesy of Green Mountain Technologies.

In existing surcharge laws, the term “recycling” is often used broadly and includes composting, whether implicitly or explicitly. Recycling has a broad definition involving the process of transforming waste into (re)usable items, therefore composting, the process of transforming organic waste into a valuable soil amendment, is understood to be included in most definitions of recycling. Wisconsin is one state in which the absence of composting-specific language in the legislation actually restricts grant funds from being available for composting projects. This demonstrates the significance of specifying composting in addition to recycling where possible in order to emphasize its value as a waste diversion method.

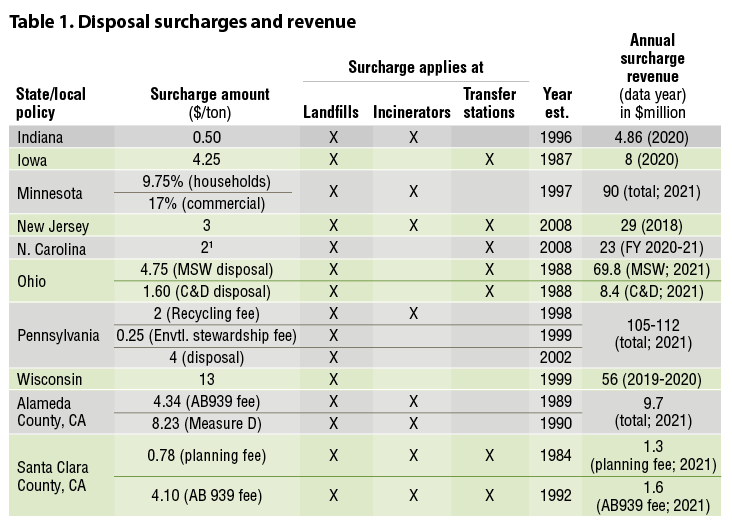

The 10 frameworks analyzed exhibit clear paths for funding to flow from disposal surcharge revenue to recycling and composting programs, projects, infrastructure, and education. Featured states include New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Minnesota, Wisconsin, North Carolina, Iowa, Ohio, and Indiana. Included in this analysis are Alameda County and Santa Clara County in California, also great examples of surcharge policies and waste diversion grant programs administered at the local level. Other states (e.g. Arizona, Illinois, Michigan, Mississippi, Colorado, West Virginia) have similar programs that may focus on more general waste management versus specifically ones that fund waste diversion.

Table 1 summarizes key data of each state or local program. In general, waste haulers pay the disposal surcharges at the disposal site. In the unique case of Minnesota, the surcharge is collected at the generator level; households and businesses are billed directly based on waste generated. Surcharge collection and resulting grant programs are typically administered by the state or local government’s designated environmental agency. Most of the example states and counties use surcharge revenue to provide financial assistance to local governments for waste diversion. Some also use the revenue to administer competitive grants for waste diversion projects by various non-government entities such as academic institutions, nonprofits, for-profit businesses, and other organizations.

This link provides details on each state/local surcharge type. 1Disposal tax

Another way that states and counties use surcharge revenue is to fund other environmental programs. These include land remediation, such as Pennsylvania’s Growing Greener Plus watershed restoration and mining reclamation projects; North Carolina’s cleanups of hazardous sites; Wisconsin’s land cleanup and remediation programs; Minnesota’s landfill cleanup and environmental monitoring; and Ohio’s litter prevention and cleanup projects. Alameda County’s surcharge revenue supports carbon farm planning, sustainable landscaping, and energy efficiency programs.

The Glacial Ridge Compost Facility in Hoffman, Minnesota received a SCORE grant from the state to help cover capital costs. The site is permitted to receive 15,000 tons/year of source separated organics. Photo courtesy of Engineered Compost Systems

Investment And Impact On Diversion

The surcharge-funded grant programs analyzed have each provided significant investment into waste diversion programs and infrastructure, demonstrating tangible impact on waste reduction, reuse, recycling, and composting. In Indiana, 2020 grant awards from both the Community Recycling Grant Program and the Recycling Market Development Program totaled over $1.8 million, creating up to 47 new jobs and increasing the amount of recycled materials by almost 85,000 tons. In Minnesota, SCORE (Select Committee on Recycling and the Environment) grants to counties provide support for county compliance with the state-mandated 35% minimum recycling rate, with 50% of the grant funds to be used for organics recycling programs.

Iowa’s Solid Waste Alternatives Program provides financial assistance to various projects including community education and training on composting, on-campus food waste composting, construction of a concrete composting pad for a school project, and purchase and use of compost spreaders to encourage application of compost on lawns. Also, Iowa’s Food Storage Capacity Grant Initiative awarded over $400,000 to 80 entities in 2020 and 2021 to expand food storage capacity and avoid wasted food.

New Jersey’s Department of Environmental Protection awarded $16 million in grants to fund municipal and county recycling programs in 2021. In 2020, Pennsylvania’s Food Recovery Infrastructure Grant provided $9.6 million to 145 projects focused on diverting edible wasted food from landfills, rescuing almost one million pounds, and distributing the recovered food to over 25,000 state residents over the course of the year. StopWaste Waste Prevention Grants in Alameda County allocated over $580,000 in 2021 to local nonprofits and businesses for waste reduction and diversion, in addition to allocating almost $5 million to municipalities for recycling program expansion.

Lessons Learned

Each disposal surcharge policy and its relationship to recycling, composting, and other environmental efforts is unique, with its own pros and cons. Surcharges serve as a self-funding mechanism to both build recycling infrastructure and disincentivize waste disposal in landfills. They are an effective tool where lack of funding is a hindering factor for the passage or long-term success of sustainability related legislation. Provision of accessible incentives to reduce and divert waste paves a clearer direction for households, businesses, waste facilities, and communities.

Based on ILSR’s analysis and comparison of various policies, the following are considerations for others interested in constructing similar policies:

- Have a designated fund that collects revenue from the surcharge and commits those funds to composting/recycling programs. Protecting and responsibly managing the revenue is imperative in order to avoid unnecessary fund diversion away from appropriate environmental and sustainability programs.

- Direct the funding and resulting recycling/composting/waste reduction initiatives locally toward the same communities that the surcharge affects. This encourages maximum waste diversion and ensures that those potentially affected by higher waste disposal fees have access to waste disposal alternatives as well as resources and education.

- Educate waste generators (e.g., businesses, households, commercial facilities) about the surcharges so they are incentivized to reduce their waste disposal and are able to negotiate with their waste haulers for lower trash disposal fees (as they reduce and recycle more waste). Education by local and state governments is critical.

- Ensure grants are accessible to smaller, community-scale projects so there is a wide and distributed investment in waste diversion infrastructure and support. A simple and streamlined application process, along with equitable priority factors, pave the way for a variety of applicants to apply for financial assistance.

Potential Roadblocks

A potential issue on the financing front is that, if generators successfully reduce the amount of waste sent to landfills, revenues from per-ton disposal surcharges will decline over time. This is exemplified by the City of San Jose, which has charged a disposal facility tax of $13/ton since 1992. Revenue data from 2002-2013 shows a steady decline in annual revenue from the tax (from $16.3 million in 2002-2003, to $10.7 million in 2012-2013) as annual landfill disposal tonnage decreased. However, landfill disposal has increased recently with higher waste generation levels and population growth, creating a steady annual revenue of $12 million to $13 million/year since 2013. Ideally, waste reduction and diversion efforts would yield consistent reductions in waste disposal rates, resulting in lower annual revenue year-to-year given a consistent per-ton surcharge rate.

One way to mitigate this effect is to implement a surcharge or fee that increases every few years, both disincentivizing waste disposal in favor of reduction or recycling and maintaining the revenue flowing in to ensure continued funding to recycling and composting projects and infrastructure. Alternatively, legislative text might include a clear mechanism for reviewing and updating the surcharge or fee, as exemplified by Alameda County and Ohio’s Soil and Water Management District waste generation fees.

Other issues associated with increased costs of disposal may arise. For example, while passing off costs to individual, household, and business waste generators can disincentivize wasteful habits of the generators, not all individuals have the means to pay for the costs of waste production in a society that doesn’t necessarily give them options other than to produce said waste. There should be a certain level of responsibility for organizations and governments to support restorative and sustainable projects and practices in addition to paying the appropriate costs for waste disposal.

Another concern voiced by communities is that even slightly higher costs associated with waste disposal would exacerbate illegal dumping. In this case, it is important that revenue from the surcharge is being managed responsibly and in part directed toward community-oriented efforts that address and mitigate illegal dumping. Examples include expanding waste reduction and diversion programs to make reuse/recycling/composting more accessible, litter cleanup and maintenance, and providing education and technical assistance. Ideally, with greater education, litter prevention capacity, and community support for and access to waste diversion and reduction options, the benefits of a waste disposal surcharge will outpace and eliminate any potential exacerbation of the illegal dumping problem.

Waste disposal tipping fees are in place to support and maintain waste disposal systems. Adding a surcharge to existing tipping fees is one successful mechanism to fund solutions to the burn-and-bury paradigm. Waste disposal surcharges penalize “the bad,” while incentivizing “the good.” The present widespread adoption of, and consistent increases in, disposal site tipping fees indicate that tipping fees are here to stay. Why not utilize a surcharge to direct revenue toward building alternatives to waste disposal systems?

Sophia Jones is a Policy Fellow with ILSR’s Composting for Community initiative, where she researches, analyzes and supports the building of U.S. policy that advances local composting.