Niche haulers collecting food waste are encountering restrictions — and opportunities — posed by solid waste franchise agreements.

Craig Coker

BioCycle May 2018

The growth of source separated organics (SSO) diversion programs has sparked the emergence of specialty contractors that primarily haul organics, such as food waste from various points of generation to composting and digestion facilities. These haulers range from local and low tech, e.g., bikes with trailers, to independent specialty haulers, to some of the major waste management companies.

Niche organics haulers include collection services using bikes and trailers (Zero to Go trailer shown).

There are obvious challenges to having multiple collection vehicles plying the roads collecting trash, source separated yard trimmings, and other SSO. These include safety risks, traffic congestion, and wear-and-tear on asphalt pavement. In communities with unregulated waste collection (the 100% free-market option), there could be 8 to 10 trucks per week on any one street collecting wastes.

Larger municipalities have begun to address these issues through use of waste collection zones and franchise agreements. A waste collection zone is a designated area of a municipality assigned to contractors for collection services. Contracts to service a zone (a franchise) are awarded following a competitive procurement and are usually set up for a multiyear term. Often, these zones are assigned, monopolistically, to a single contractor.

Smaller communities have adopted this practice as well. In a large rural county in Virginia with a population of 33,000, waste and recyclables collection is divided into five zones, each handled exclusively by a different collection service. Some communities, like Pasadena, California, have adopted nongeographically exclusive franchise systems, which are, in reality, local permit-issuance programs. There are 18 approved/licensed/permitted haulers that households can choose from; no others can haul in Pasadena.

Those in favor of franchised zone collection models claim the public sector has more control over the waste management collection process, that municipalities can enforce requirements for clean fuel trucks and more expansive diversion programs, and that long-term contracts provide an incentive for haulers to invest in the infrastructure (bins, dumpsters, compactors, trucks, etc.) needed to support high diversion rates.

Opponents of the practice decry the loss of the historical open market approach to collection services and claim that costs will increase due to the monopolistic aspect of franchised collection and that jobs will be lost due to the nonfranchisees’ loss of business. Another adverse effect is that niche food waste haulers and composters who like to do their own collections can be blocked from providing that service.

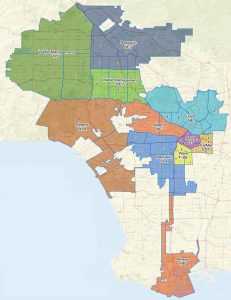

Figure 1. Regions in various colors represent the city of Los Angeles collection zones. Image courtesy of City of Los Angeles Department of Public Works

Collection Shift In Los Angeles

Commercial and residential franchise collection zones are found mainly on the West Coast in Seattle, Portland, and many California counties and cities. In December 2016, the city of Los Angeles awarded 10-year contracts worth $3.5 billion to seven haulers to manage collection in 11 zones (Figure 1), a significant reduction from the former system in which 144 private haulers were collecting from multifamily and commercial sites (although 99% of the sites were served by 15 haulers). Called Zero Waste LA, the franchise program requires the commercial haulers to reduce landfill disposal by one million tons/year by 2025, requires that all 64,917 commercial waste accounts in the City be given a blue bin for recyclables and a green bin for organics, that all trucks be clean fuel (i.e. fueled by compressed or liquefied natural gas) vehicles, and that the franchisees partner with food rescue and reuse organizations.

In addition, the haulers must submit reports on monthly tonnages collected, by waste stream, and indicate which certified facility received which waste. The disposal and processing facilities must be certified by the city’s Sanitation Department and must also file monthly reports on wastes received. Residential collection service (not including multifamily) will still be provided by the Sanitation Department. The new system went into effect in July 2017; transitions are still underway.

When Michael Martinez founded L.A. Compost in late 2012, he and his colleagues used bicycles to pick up food waste in Los Angeles neighborhoods. They soon found that they had to get permitted to collect solid waste, as required by the 1989 Assembly Bill 939, known as the Integrated Waste Management Act. Rather than pursue that option, Martinez elected to start community composting sites around Los Angeles (they now manage 24 facilities, with 6 more in development). Now, with the new franchise system coming into effect, he sees opportunities to work with the franchised haulers.

“We are working with one of the haulers for commercial and multifamily residential buildings,” Martinez explains. “The hauler’s contract with the City requires them to identify ‘resource recovery agencies’ to maximize diversion. There are a lot of grey areas here, as food waste generated on-site can’t be picked up except by licensed and franchised haulers. We can’t charge for pick ups as we are not licensed haulers. If we pick up for free, then there’s no issue in the eyes of the City. I’m also curious if we paid for food waste, would it still be considered waste, or would it be outside the waste category, would it now be a product?” As in other communities, Martinez notes that there is simply insufficient processing capacity to handle the potential amounts to be diverted.

New York City (NYC), which is in the midst of a major expansion of its SSO diversion program, released a 2016 evaluation of its commercial waste collection program with an eye towards establishing franchised zones. The current system consists of 90 private companies (called “carters”) serving 108,000 accounts, the 20 largest carters serve 81 percent of the accounts. Private collection vehicles in NYC travel more than 23.1 million miles annually collecting wastes and recyclables.

The study found that establishing commercial waste collection zones could reduce truck traffic (measured as vehicle miles traveled) by 49 to 68 percent, diesel fuel consumption by 3.5 million gallons/year, criteria air pollutants by 32 to 64 percent, and greenhouse gas emissions by 42 to 64 percent. The City has since awarded an $8 million, six-year contract to a consulting team led by Arcadis to design the new franchise collection program.

Legal Tangles

Companies and individuals who are in, or developing, food waste diversion programs should carefully research local waste hauling requirements. “We started our business in Pasadena in 2009 offering organics recycling services for small parties and special events,” explains Christine Lenches-Hinkel, founder of Waste Less Living and 301 Organics. “Our customers were very satisfied with our ability to recover all the compostable waste, including the food and tableware products. From there, we were encouraged to expand our services to schools, which we did, as well as to weekly service for families of the schools. The City of Pasadena was aware of what we were doing and acknowledged us for our efforts with mayoral awards and recognitions for small business innovation. However, they pressured us in 2013 to apply for a franchise agreement as a solid waste hauler.”

Lenches-Hinkel tried to persuade the City for an exemption, citing Pasadena’s exemption for self-haulers, since the material being recovered for the customer was the compostable dining and serviceware that Waste Less Living was selling, and the company was paid by the customer to compost these materials versus hauling them to a landfill.

Additionally, Lenches-Hinkel argued that her company did not meet the legal intent of the solid waste franchise hauling ordinance given the company did not own or operate any heavy trash trucks that would otherwise impact the roadways and thus would trigger the fees to be levied in the first place. Nor did Waste Less Living handle solid waste or recyclable materials. “The imposition of the City’s franchise fee of 23 percent on gross revenue also would have been a financial hardship on the business and would not have been economically viable, so we discontinued our services, including the party and event services,” she explains.

Later, in mid-2015, the Pasadena City Council amended its ordinance to include organics haulers that would be allowed to apply for a franchise under the closed program but would have to meet all of the same franchise hauler requirements, including the franchise fees levied. It basically allows for “new haulers that collect, transport, dispose and recycle, in the City of Pasadena, organic material to a compost facility to apply for a franchise and collect specified materials from both commercial entities and single-family residences.” There are 18 licensed haulers in Pasadena, but none of them are niche haulers focused on organics, likely due to the lack of processing alternatives.

Franchise Variations

In some cities, like Portland, Oregon, the residential collection routes are franchised but the commercial routes are not. Annette Steele with Portland’s Bureau of Planning & Sustainability explains: “Collection of solid waste, recycling and compostables is not franchised for commercial customers. This means a permitted hauler can operate anywhere within the City and commercial customers can choose any of the permittees. The City does not set commercial rates. A hauler must obtain an annual commercial permit from the City in order to operate. Portland currently has 32 commercial permitted haulers.

“Commercial permittees must offer hauling of solid waste, recycling, and compostables to any customer who requests it. They are allowed to subcontract these services if they choose and some permittees use this option rather than collect compostables themselves. With all that being said, if a company hauls only 100 percent source separated recyclable or compostable material, they are not required to hold a commercial permit and are considered an ‘Independent Recycler’. Currently, Independent Recyclers are not required to report their tonnage to the City of Portland unless they move more than 25 tons of materials a year. They do not pay a registration or tonnage fee to the City.”

In Portland, Oregon, the residential collection routes are franchised (3-stream curbside setout above), but the commercial routes are not. Photo courtesy of City of Portland

Steele adds that food waste currently falls under the category of 100 percent source separated recyclable material. “This means any company that hauls only food waste from commercial accounts does not have to obtain a commercial permit,” she notes. “For the most part, we have very few compliance issues with Portland commercial haulers. Leaking/spillage is probably the most reported compliance issue, although they are usually remedied by the hauler before our office even hears about it.”

In Washington State, the legislature decided in 2001 that operating as a solid waste collection company is a business affected with a public interest and that such companies should be regulated. As a result, the Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission (UTC) wrote rules establishing standards for public safety, fair practices, just and reasonable charges, nondiscriminatory application of rates, requirements for adequate and dependable service and requirements for consumer protection.

The Washington rules provide exemptions for haulers under contract to municipalities and for haulers of source separated recyclable materials. Unfortunately, the state’s definition of source separated recyclable materials is “those solid wastes that are separated for recycling or reuse, such as papers, metals, and glass”, but not source separated food wastes, which are still defined as solid wastes. So, composters wishing to collect food wastes must abide by the UTC rules.

“That was the situation we found ourselves in,” says Pierce Louis, co-founder of Dirt Hugger in Dallesport. “As we are only two miles from the Columbia River on the Washington side, we obtain our feedstocks from both Washington and Oregon and the rules are very different. We were providing collection service to one municipality in Washington, but when we tried to expand to a second one, we found out about the UTC rules. The rate setting and financial compliance processes were overly onerous, so we elected to get out of the curbside collection business.” Once they separated themselves from direct communications with generators of food waste, Dirt Hugger had to develop contamination surcharges and feedback mechanisms like a Hauler Feedstock Quality Report (“Regional Composter Confronts Contamination”, Jan. 2017).

As the growth in food waste diversion programs continues, there is a need for regulatory reform for solid waste definitions at both state and local levels. Most state environmental regulations define solid waste as where it comes from (i.e. municipal or industrial in origin), not what it comprises. Compostable serviceware is a case in point. Many consider it a recyclable commodity, but once it is discarded into a compostables bin or a trash can, it becomes part of the municipal solid waste stream. State programs looking at rewriting and updating their composting regulations should consider definitional updates as well. For example, Pasadena City Code defines food waste as “any material that was acquired for animal or human consumption, is separated from the municipal solid waste stream, and that does not meet the definition of agricultural material. Food waste may include material from food facilities as defined in Health and Safety Code Section 113785, grocery stores, institutional cafeterias (such as, prisons, schools and hospitals) or residential food waste collection.”

Craig Coker is a Senior Editor at BioCycle and CEO of Coker Composting & Consulting near Roanoke, VA.