What happens to spent malting grains from the craft breweries, coffee grounds from cafés, leftovers in the award-winning kitchens, and the old frying oils from food trucks and diners?

Sean Clark

BioCycle April 2013, Vol. 54, No. 4, p. 20

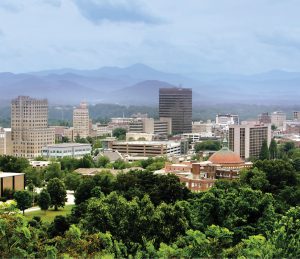

Asheville, North Carolina

Asheville, North Carolina, has gained a national reputation as a hub of local and artisanal foods. In fact, the local foods movement in this Southern Appalachian city has become so embedded in the community consciousness that the city has dubbed itself “the world’s first Foodtopian Society.” There are hundreds of unique restaurants, dozens of bakeries, breweries and cafés, and over a dozen tailgate farmers markets in this city of about 85,000 people. And according to Maggie Cramer, communications manager for the Appalachian Sustainable Agriculture Project (ASAP), there’s been a five-fold increase in the number of restaurants sourcing local foods in the Asheville region over the last decade.

“You can’t open a restaurant in the Asheville area without making a commitment to support local farmers,” says Cramer. “It’s what consumers want and what chefs know they can get.” ASAP, a nonprofit based in Asheville, supports farmers in western North Carolina in a variety of ways, including publishing a popular local foods guide that helps connect consumers to farmers. The number of farmers in that guide has increased by over 800 percent since it was first published 10 years ago. And those farmers are always trying to grow or raise new foods for this demanding market.

Coffee grounds from Clingman Café (shown by barista Genevieve Van Zandt) are one of the main ingredients used by Asheville Fungi in its mushroom-growing substrate.

What may not be as obvious is the care and innovation that’s occurring with the stream of organic by-products, residuals and wastes that inevitably follow from the more celebrated farm-to-table segment of the food cycle. What happens to spent malting grains from the craft breweries, used coffee grounds from cafés, leftovers in the award-winning kitchens, and the old frying oils from food trucks and diners? It turns out that there’s been just as much creativity in this less visible sector of the local food system. And the experiences of Asheville in capturing and using food wastes and by-products — the successes as well as ongoing challenges — can serve as useful examples to communities in the Appalachian region and beyond for what’s possible.

Processing Grains

North Carolina has one of the most diversified agricultural economies of any state. It’s a leading producer of such varied products as hogs, trout, turkeys, sweet potatoes and cucumbers. According to the North Carolina Department of Agriculture, farming plays a major role in the state’s economy, accounting for nearly a fifth of the state’s jobs and income. But it’s generally not considered a major player when it comes to grain production and processing. When wheat prices hit historically high levels in 2008, Jennifer Lapidus, Asheville artisanal baker, became concerned about the future availability of flour and what it might cost. “The cost of the baker’s most essential ingredient rose as much as 130 percent,” she recalls.

Like all bakers in the Asheville area, Lapidus was dependent on distant sources of grain and at the mercy of commodity prices that seemed less predictable. Her answer to the simple question, “why don’t we grow bread wheat in North Carolina?,” drove her to establish Carolina Ground, a stone-milling L3C dedicated to serving as a link between regional farmers and bakers. (An L3C is a low-profit liability company, essentially a social enterprise that bridges the gap between nonprofit and for profit investing.) To Lapidus, this was a tangible way to improve security and sustainability. By finding willing farmers, seed cleaners and bakers, she created a mechanism and assembled the infrastructure for local grain farmers to find a regional market for their products and for bakers to gain access to regionally-produced grains and locally-milled flours. The wheat and rye flours that Carolina Ground produces are used by over a dozen bakeries and restaurants in Asheville.

Riverbend Malt House, which produces malted wheat, barley and rye for the craft brewing industry, is located in a former grocery warehouse. A room that had been used to ripen bananas has been repurposed for the malting process (barley shown).

Lapidus found allies in her quest for local grain in Brent Manning and Bryan Simpson, cofounders of Riverbend Malt House. Established in 2011, Riverbend produces malted wheat, barley and rye for the vibrant craft brewing industry. Before it opened, the only local ingredient in Asheville’s craft beers was the water. Now, a handful of craft breweries in Asheville are using some regionally-grown grains malted by Riverbend.

Both processes, milling and malting, generate organic residuals. In the case of milling, grain middlings result from the bolting or sifting process that separates out larger particles from the whole stone-milled grain, leaving a finer final product that bakers prefer for some applications, such as lighter pastries and breads. Carolina Ground’s middlings end up as livestock feed, just as they have throughout the millennia of grain milling. This year, Carolina Ground will be getting a whole hog, in the form of custom-processed pork, raised on its own middlings.

Malting — the process by which grains are prepared for brewing — involves three stages: steeping, germination and kilning. Riverbend adapted a building originally built as a grocery warehouse, and uses the climate-controlled room designed for ripening bananas, for the steeping and germination stages. Once steeped, the wet grain is spread out on a concrete floor and allowed to germinate. In the last stage, the grain is transferred to a hot-air kiln to stop the germination process without destroying enzymes necessary for brewing. Following kilning, the grain is “debearded” to remove the rootlets before bagging for the breweries or packing into home-brewing kits. These dried rootlets, along with broken or undersized kernels, end up as a by-product that has several uses. Some goes to small-scale egg producers as an absorbent bedding for the laying hens. But another local emerging market for this by-product is specialty gourmet mushroom production.

The basement of the Mushroom Central store serves as a growing room. Business owners Chris Parker (inset, left) and Joe Allawos (right) display some of the residuals from businesses in Asheville that are used as substrate to produce mushrooms.

Raising Fungi

Chris Parker and Joe Allawos, opened their store, Mushroom Central, in West Asheville in 2012 as an extension of their business Asheville Fungi. Their partnership formed out of a mutual passion for hunting and raising mushrooms and their shared belief that mushroom farming can be done successfully in an urban setting. The store sells mushrooms, fungal (mycelium) cultures to other producers, and the equipment needed for small-scale home production. The basement serves at their growing room, where a variety of organic materials captured from the waste stream are used as substrates for producing about a dozen different gourmet mushrooms, such as elm oysters, king oysters and lion’s mane, for area restaurants and retail customers.

The main substrate ingredients include wood shavings from a nearby wood-worker, coffee grounds from the Clingman Café (about a mile away) and malted barley by-product from Riverbend. These residuals are pasteurized, packed into sterile bags and inoculated with fungal spawn. Mushroom Central taps into another organic waste stream as well — the top branches of healthy oaks and poplars cut down by tree maintenance services — and inoculate them for mushroom production in log culture.

Culturing and cultivating fungi in Asheville doesn’t end with gourmet mushrooms. Sarah and Chad Olipant started Smiling Hara Tempeh in 2009 and supply grocery stores and restaurants in North Carolina and adjacent states with their vegan products. Tempeh is produced by culturing cooked soybeans. During processing, the soybeans are dehulled and broken into pieces using a commercial coffee grinder prior to soaking and inoculating with a Rhizopus fungal culture. “We’re growing a tropical fungus and it’s similar to indoor mushroom farming,” explains Chad Olipant. The only wastes generated during the process are the hulls and dust from dehulling process, which are sent to Asheville Fungi to be mixed in with their mushroom substrates.

Brewing By-Products

Fermentation in tempeh production may be unfamiliar to many, but the same process is also fundamental to brewing beer —a lot of that is happening in Asheville. Since 2009 Asheville has held or tied for the title of the Beer City, USA, an annual online poll. Over a dozen craft breweries operate in and around Asheville and plans for more are in the works. The process of brewing beer involves subjecting malted barley, and sometimes other grains, to yeasts that consume the available carbohydrates and produce alcohol and carbon dioxide. Other flavorings, typically including hops, are also added. In order for yeasts to access the energy source, the malted grain is mixed with water and heated in a process called “mashing.” Enzymes in the malted grain break down starches into simple sugars that are dissolved into the liquid or wort.

Once mashing is complete, the wort is fermented into beer, leaving the spent grains as a by-product. Though amounts vary with different recipes and types of beer, about two pounds of dry malted grain are required per gallon of beer produced. Literally tons of spent, wet brewer’s grains are produced daily in Asheville. Fortunately, this material has a variety of potential uses, including serving as mushroom substrate, compost feedstock, biomass fuel, and even a baking ingredient. But most of what’s produced in Asheville becomes a feed for dairy and beef cattle, and hogs. The strong demand for local meat and dairy products drives this since there are many nearby farms eager to take the material and little flat land around for feed grain production.

Fryer To Fuel Tank

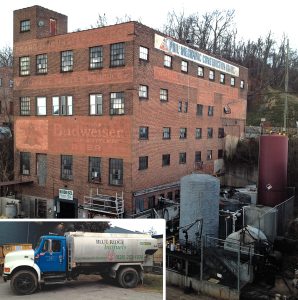

Farms around Asheville are getting more than just livestock feed and bedding from the city’s organic waste stream. Some, like Jamie Ager, co-owner of Hickory Nut Gap Farm, are also getting fuel. This certified organic farm produces grass-finished beef, pastured pork, and a variety of fruits and vegetables. In keeping with the farm’s commitment to sustainability, Ager uses biodiesel blends from Blue Ridge Biofuels to power the tractors on the farm. Blue Ridge Biofuels was started as the Asheville Biodiesel Cooperative and actually occupied a shed at Hickory Nut Gap Farm in the early years of its operations. It incorporated in 2005 and now has nine employees making over 300,000 gallons of biodiesel annually — with capacity to produce one million — from used vegetable oil it buys and collects throughout western North Carolina. It has about 500 collection accounts in the region that it services with three vacuum trucks (which run on biodiesel).

Blue Ridge Biofuels buys and collects used vegetable oil from about 500 accounts in western North Carolina. It produces three blends in a former grocery warehouse and delivers fuels (inset) to about a half dozen gas stations in Asheville.

According to Woodrow Eaton, general manager and founding member of the employee-owned company, most of the biodiesel produced is sold as three products at about a half dozen gas stations in Asheville: B20, B50 and B99. The production process involves collecting the used oil, transporting it to the company’s facility in a former grocery warehouse in the River Arts District of Asheville where it is cleaned of food particles and dewatered, and then carrying out the chemical reaction, technically known as transesterification. Because the waste methanol generated during the process is completely recovered and reused, the only by-product generated is glycerin, which is sold to a refiner that cleans and resells it.

Blue Ridge Biodiesel is now participating in a collaborative feasibility project called “F3.” The three Fs refer to field, fryer and fuel tank. Locally produced canola will be pressed into food-grade oil, used in Asheville restaurants, and then collected and turned into biodiesel for transportation and home heating. The grant-supported initiative is starting with 50 acres of canola grown in Asheville and should be a good test of the potential viability of localizing not only cooking oils but also renewable fuel.

Food Recovery And Diversion

Despite the economic, environmental and social costs, a tremendous amount of food in the United States is wasted — and most of this uneaten food unfortunately ends up in landfills. In Asheville, however, there are many intentional and coordinated efforts along the food supply chain and waste stream to capture and use food before it finds its way to the landfill. These rely on community collaboration, ingenuity and good communication for success.

Student volunteers from a food donation group, Food Not Bombs, prepare meals for the homeless in a campus kitchen and bring them to downtown Asheville to distribute.

It’s not hard to find community organizations engaged in helping those in need and improving the quality of life in Asheville. MANNA is an established, well-known nonprofit that connects the food industry with community organizations addressing hunger throughout western North Carolina. It distributes food donated by local farmers, grocery stores, food processors and food drives. Another, much smaller, volunteer organization with a similar aim is Food Not Bombs. Student volunteers from the University of North Carolina, Asheville (UNCA) and Warren Wilson College, who are actively involved with the loose-knit organization, get donations of food nearing their expiration dates from area grocery stores and use them to prepare vegetarian meals for the homeless. A kitchen on the UNCA campus is used to prepare the foods and bring them to Pritchard Park in downtown Asheville every Sunday morning.

Of course, some food isn’t recovered — and that’s where Danny Keaton comes in. He owns and operates Danny’s Dumpster, which started as a hauling business to handle recyclables, compostables as well as trash destined for landfill. When the small composting operation Keaton relied on in the city stopped accepting materials in 2012 and prepared to close, he had nowhere to take the food waste collected from grocery stores, restaurants and schools. After a difficult few months, Danny’s Dumpster struck a deal with the city of Asheville to use six acres of its land for a new composting facility in exchange for accepting and composting the city’s green wastes. The new facility opened in October 2012.

Composting is a new experience for Keaton, but he seems to be up to the challenge. He has about 80 commercial or institutional accounts for his hauling service; about 60 use the composting option. These include restaurants, grocery stores, a hospital, a college, a university, and a group of five public elementary schools that collectively include over 1,000 students. (According to Keaton, this is the first official public school composting program in North Carolina.) He and his two employees are handling about 30 tons of food waste weekly. The restaurants are particularly challenging since they need to be serviced 3 to 4 times/week and typically can’t make it through a weekend without at least one pickup.

Danny Keaton, owner of Danny’s Dumpsters, recently expanded into operating a composting facility after the site he was hauling to closed in 2012. About 60 of the company’s commercial and institutional collection accounts participate in diverting their organics.

Danny’s Dumpsters has three roll-off in-vessel composting units supplied by Advanced Composting Technologies and is planning to add more in the near future. The food waste is mixed with landscape waste and held in the vessels for 2 to 3 weeks for a quick heat-up period before being windrowed for several months. All leachate is collected in an aerated, underground tank. Once finished compost is ready for sale, Keaton plans to market to the local landscape industry, which will likely be more lucrative than selling to farmers. He is negotiating with New Sprout Organic Farms as well but the compostable utensils included in the feedstock stream could prevent a deal since these may not be permitted in USDA-certified organic systems.

The food waste stream from Asheville’s households is also getting some attention. A Raleigh-based company called CompostNow is surveying the attitudes of Asheville residents to assess the potential viability of a residential organic waste collection and composting service. The company, which already operates successfully in other parts of the state, has set up a website explaining its services and fees and is requesting feedback from Asheville residents.

What distinguishes Asheville from most other cities is not the entrepreneurial spirit, the social and environmental consciousness, or the ubiquitous and deep commitment to the local culture, community and economy. It’s the balanced combination of all of these. Asheville suffered under heavy debt and sluggish economic growth from the 1930s until the 1980s, stifling innovation and development. But in just the last decade there has been an amazing transformation that’s evident in the solar hot-water and photovoltaic panels seen on restaurant roofs, recycling and compost receptacles that are standard in cafés, the self-service bicycle repair stations along sidewalks, the charging stations for electric cars, and of course the renowned local foods and brews. While duplicating exactly what’s happening in Asheville may not be realistic, perhaps other communities can learn from its experiences and implement their own foodtopian experiments.

Sean Clark teaches and directs the educational farm at Berea College in Kentucky.