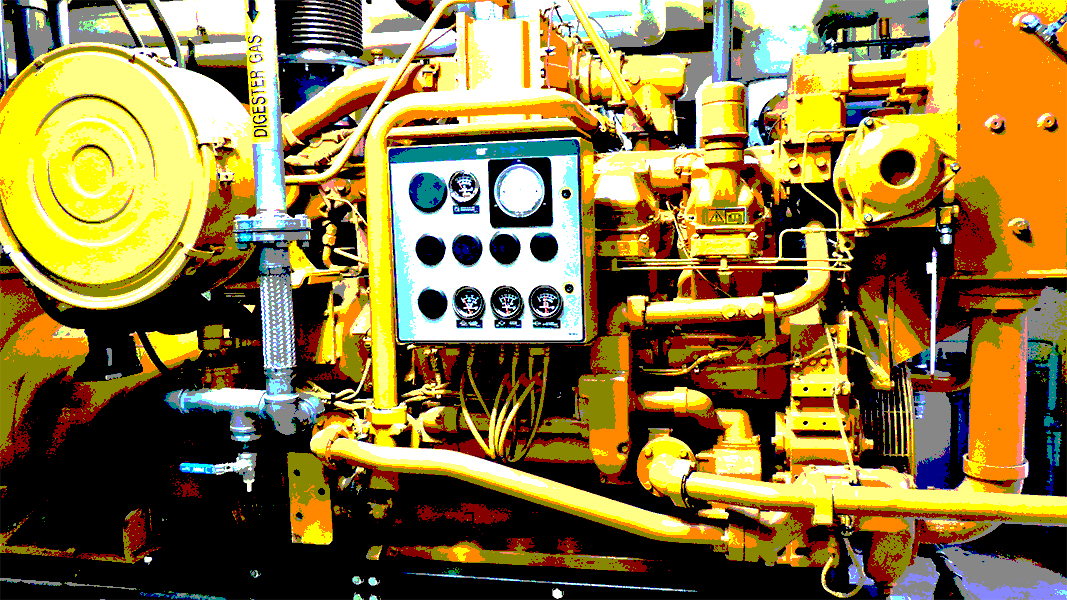

Top: Photos/collage by Doug Pinkerton

Michael H. Levin

In 2016, BioCycle forecast a supercharged future for anaerobic digestion (AD) from (e.g.) the convergence of nation-by-nation greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction goals under the Paris Accords and the Obama Clean Power Plan (“CPP1”) (Levin, 2016; Walsh, 2016). That prediction seemed to go south when the Supreme Court killed CPP1 and countries repeatedly fudged their Paris commitments (Carrington, 2023). But with new investment tax credits in the Inflation Reduction Act for “green gas” producers (Levin, 2022), and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) proposed successor to CPP1 (Puko, 2023; EPA, 2023), that prediction may be rising again.

CPP1 aimed to reduce power sector carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions about 30% from 2005 levels by 2035. Under the Clean Air Act’s New Source Performance Standards, “new” coal-fired electric generating units (EGUs) would have been directly required to install carbon capture and storage reducing about 30% of their CO2 emissions. Under parallel CPP1, “existing” EGUs that contribute most of the power sector’s 25% of domestic GHG emissions would have been indirectly regulated by the states under EPA-approved state plans.

For those plans, EPA departed from its typical (though not exclusive) unit-by-unit “best system of emission reduction” approach. Instead, it developed state-by-state CO2 emissions caps and presumptively directed that states meet those caps through three “building blocks” — efficiency improvements at individual EGUs, shifts from coal to natural gas-firing, and shifts from coal or gas to renewable energy. The last two blocks sought to achieve reductions the way powerplants and grids actually operate: by constantly shifting generation between different EGUs as an integrated real-time system.

In legally bizarre decisions, the Supreme Court first suspended CPP1 before an appeals court even could address it, then struck it down. Invoking a new “major questions doctrine” purportedly triggered when an agency “suddenly discovers power to address questions of vast social or economic importance,” it invalidated CPP1 because the Clean Air Act did not specifically authorize EPA to direct generation-shifting from coal-fired EGUs to natural gas or renewable EGUs. (West Virginia v EPA, 597 U.S._(2022); Levin 2022a)).

Despite some sweeping statements, all the Court held was that EPA could not purport to mandate top-down generation shifting from dirtier to cleaner units. It appeared to recognize that traditional fuel-switching, coal-cleaning or other reduction measures applied to individual EGUs (but not necessarily within their fence lines) remained permissible. It also appeared to recognize that generation-shifting is acceptable where it’s not (in effect) mandated by EPA, but results from individual state or EGU compliance decisions. Meanwhile, shale gas and renewables booms had made CPP1 obsolete: its 30% reduction goal was achieved through market forces more than a decade early.

Proposed CPP2

Proposed CPP2 builds on the distinctions above. Out are statewide CO2 emissions caps and top-down generation shifting. In are what might be called “West Virginia shields” where EPA quotes the Court’s permissibility passages back at it — plus 13 subcategories of existing EGU types with varying source-specific CO2 emission limits based on size, fuel type, and remaining useful life (i.e., whether or when they plan to shut down).

Under state plans, large existing long-life coal-fired units presumptively would be subject to carbon-capture-and-storage (CCS) that ramps to about 90% capture and 88% reductions. Large existing long-life gas-fired combustion turbines would presumptively be subject either to similar CCS requirements, or to hydrogen (H) co-firing that ramps to 96% by volume and over 90% reductions. Most other coal or gas units would be subject to less stringent presumptive limits if they shutter by specified dates (as many have plans to do). Large gas-fired “peaker” units that run at low annual capacity to support grid reliability would be exempt, unless EPA covers them downstream.

Compliance would occur over a roughly 15-year timeframe to allow for availability of CCS or H co-firing, including new CO2 or H pipelines. States would have substantial latitude to develop “more flexible” plans that yield reductions “equivalent” to their presumptive overall emission limits.

A final CPP2 is expected in Spring 2024. If implemented, reduction obligations for a big chunk of the power sector could create large near-term AD opportunities, even with far off compliance dates. That’s because utility system planning and finance decisions require commitments many years before actual compliance. Markets generally “bake in” added value from the expected demand such commitments create. Thus, if existing coal or gas EGUs seek to comply by using renewable natural gas (RNG) from AD facilities, RNG value and AD revenues likely will rise.

If CPP2 is implemented, reduction obligations for a big chunk of the power sector could create large near-term AD opportunities. Photo by Doug Pinkerton

What’s In CPP2 For AD?

While not a final rule, the proposal highlights potentially helpful outcomes for AD.

- Fuel exclusions. CPP2 proposes to continue EPA’s traditional exclusion of “biogas” (e.g., landfill or digester gas) from “natural gas” fired by existing power plants, meaning RNG should be considered “non-fossil.” However, it also seeks comment on whether biogas treated to pipeline quality standards should be reclassified as natural gas due to “non-variability.” Commenters pushed back, noting that all treated biogas should be excluded and reclassification would undercut national renewable energy policy by penalizing RNG. They also asked that firing with RNG be designated a separate “best system of emission reduction.” Apart from possible branding benefits, it’s unclear why the second ask might matter — while firing RNG produces the same volume of CO2 as firing natural gas, many affected EGUs’ emission limits might proportionately be met the more RNG they fire, and “wholly non-fossil” EGUs which fire less than 11% fossil fuel would be exempt from new requirements. Thus, core benefits of these incentives would seem to flow to AD facilities regardless — if the exclusion is maintained.

- Co-benefits. Where CPP2 would cause CCS installation or H co-firing at EGUs, “side benefit” demand could produce extra revenues for AD. For example, firing RNG can produce relatively pure concentrated CO2 streams that are easier and less costly for CCS systems to capture, and can reduce local criteria pollutants. RNG also can be a feedstock to produce qualifying “green hydrogen” through renewables-powered steam methane reforming (SMR) or chemical pyrolysis — routes that may avoid energy and resource intensive electrolysis of water while mitigating the heavy demand for qualified green H that a final CPP2 is expected to drive.

- More pipeline access. To transport additional co-fired natural gas — as well as “green H” and CO2 captured by CCS — CPP2 would surge main and lateral pipeline construction well beyond the current natural gas network. While there are short-term technical issues, dual- or triple-use pipelines likely will have to be deployed in advance of CPP2’s compliance dates. Combined with billions of dollars for new or improved pipelines in the $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA, 2021), this could reduce pipeline constraints for already connected AD facilities while speeding connection for others.

- Emissions trading. BioCycle long ago noted that AD facilities may qualify for multiple benefits (e.g., saleable credits for displacing fossil fuels, and for reducing nitrogen-ammonia transport from manure spreading) under CPP-type state plans (Levin, 2016b). As proposed, CPP2 would delegate states broad discretion to adopt “more flexible compliance plans” — including a range of emissions averaging or trading regimes, within or beyond state borders — as long as “equivalent” overall reductions result. Comments, ranging from groups asserting CPP2 is “unlawful over-reach,” to state and environmental groups pressing for more stringent reductions, overwhelmingly supported expansive state options.

A few points seem worth noting here.

- CPP2 suggests constraints such as limiting averaging to single or co-owned powerplants or limiting trades to within certain EGU subcategories. But it does not propose these limits. It merely seeks comment on them, possibly as part of a strategy to blunt attacks based on West Virginia by showing broad bottom-up support for more robust options.

- CPP2 acknowledges that no state is legally required to copy EPA’s “best systems” or their presumptive emission limits. It also notes that emissions trading regimes make little sense absent a “thick market” comprising many credit buyers and sellers with disparate reduction costs. These statements undercut the constraints CPP2 suggests. They imply that a state (or group of states) could adopt a full-blown cap-and-trade power-sector emission reduction program, or anything “equivalent” short of that. Numerous state commenters asked that established emissions trading programs like the Northeast Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) or Western States cap-and-trade compact be presumptively approvable as whole or partial state plans.

- Though CPP2 focuses on powerplant CO2 reductions, it makes numerous references to CO2-e (carbon dioxide equivalents) — the six gases including methane that EPA designated a “single pollutant” in its seminal GHG endangerment finding (see Massachusetts v. EPA, 549 U.S. 497 (2007)). Nothing in the Clean Air Act would seem to bar a state from authorizing AD facilities to secure credits for reduced methane emissions (at 25 to 80 times the equivalent CO2) and sell those credits to EGUs seeking to comply with CPP2-derived emission limits, as long as double counting and certain reductions that would have “happened anyway” are addressed (Levin 2016c).

In sum, CPP2 may be better for AD than business as usual or CPP1. Whether that’s true will take more litigation — added to the already most litigated Clean Air Act matter of the 21st century — to determine.

Further Reading

Carrington, “Chasm between climate action and scientific reality laid bare in UN stocktake,” The Guardian (Sept. 8, 2023).

EPA, “New Source Performance Standards for GHG Emissions from New, Modified, and Reconstructed Fossil Fuel-Fired EGUs; Emission Guidelines for GHG Emissions From Existing Fossil Fuel-Fired EGUs . . .,” 88 FR 33240 (May 23, 2023).

EPA, “Greenhouse Gas Standards and Guidelines for Fossil Fuel-Fired Power Plants,” (last updated Aug. 3, 2023).

Levin, “IRA Revolutionizes AD Tax Credits,” BioCycle (Aug. 23, 2022).

Levin a, “The Supreme Court Strikes Down Common Sense,” National Law Journal (Oct. 5, 2022).

Levin b, “Is Nutrient Trading Poised for A Surge?” BioCycle (June 2016)

Levin c, “Lessons from the Birth of Emissions Trading, Part 1,” BioCycle (May 2016)

Puko, “EPA floats toughest-ever limits on power plant pollution,” Washington Post (May 12, 2023)

Walsh, “Biogas and the Clean Power Plan,” BioCycle (Jan. 2016)

Mike Levin, a BioCycle Contributing Editor, is managing member of the virtual law firm Michael H. Levin Law Group, PLLC (Washington DC) and a principal in NLGC LLC and Solar Shield LLC, which respectively focus on capital formation for renewable energy projects and optimized development of rooftop PV systems in the District of Columbia area. From 1979-1988 he was National Regulatory Reform Director at the U.S. EPA.