Sally Brown

In this time of isolation, we can reflect on the impacts of personal choices and actions on building a sustainable society. That sounds pretty high and mighty. But what it really boils down to is this: How bad is it for the planet to expand your wardrobe? How much difference can it make to go all out and not only clean your closets but limit your purchases?

There are two routes you can take with your wardrobe in the time of COVID-19 that can benefit the environment and they are not mutually exclusive. One involves purging. Judging from my own experience, this seems like a common approach in the Pacific Northwest. Based on a recent trip to Goodwill, it seems like everyone in Seattle spent much of the quarantine reading the Marie Kondo book about decluttering and cleaning out their closets. For me it was all of those single use paper bags from the supermarket that served as my inspiration. Armed with a car load of clothing to donate (putting those bags to good purpose) I got in the one-hour long line of cars to donate the clothes to the local Goodwill. This was not at a peak weekend time. This was late morning on a Wednesday.

The other side of that coin involves how you shop for new clothes. Buying more clothes is one way to ease the pain of the pandemic. My extra time online has led to the purchase of a pair of too expensive “pajama pants” with a lovely floral print not intended to be worn in bed (bought new and not likely to be worn often) and two “new to me,” i.e., used, sweaters that will likely be worn to death. I am sure that others have gone down a similar path these last few months. Buying clothes isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Buying too many, all new, and wearing only a few of them is a bad thing. The problem is that is what most people do.

Carbon Footprint Of Clothes

Carbon Footprint Of Clothes

Clothes are complicated. The carbon footprint of clothes is just one part of it — 1.2 billion tons a year (Ellen MacArthur Foundation). Also take into consideration the environmental and human impacts. Multiple books for a general audience have been written on this topic:

- Fashionopolis: The Price of Fast Fashion and the Future of Clothes by Dana Thomas

- Fugitive Denim: A Moving Story of People and Pants in the Borderless World of Global Trade by Rachel Louise Snyder

- The Conscious Closet: The Revolutionary Guide to Looking Good While Doing Good by Elizabeth L Cline

Cline says that clothing and footwear are responsible for 8% of the carbon emissions worldwide. That is equivalent to the emissions from the European Union (where they are very well dressed I might add). It is also worth a lot of money — $2.5 trillion. The environmental cost of clothing includes the impact of cultivation, dying, manufacturing and finishing, which is typically spread out across continents. A pair of stone washed jeans typically takes 18 gallons of water, 1.5 kilowatts of energy, and 5 ounces of chemicals to get its “worn” look. That estimate doesn’t take into account the water, energy and chemicals required to grow, weave, dye and sew the jeans in the first place. Carbon costs can even include the very fabric itself — all synthetic clothes including those lovely wrinkle free items, are made from fossil fuels. Polyester is plastic. These account for 63% of all textiles. In order to become a sustainable industry, emissions associated with production need to be reduced by a minimum of 30% within the next 30 years (Sandin and Peters, 2018).

What To Do?

The answer isn’t to stop buying clothing completely. That might have sounded good when you were in your 20s and lived in the tropics. Completely stopping manufacturing would wreak financial and visual havoc. One out of 6 jobs worldwide are related to clothing. Many of the people actually making the clothes work in horrific conditions. You may remember the collapse of the factory in Bangladesh that killed over a thousand people. That hasn’t slowed the industry down one bit. Before you cry out that the solution is to shut all garment manufacturing down in that country, realize that it accounts for over 80% of its total export earnings. Pay these people a livable wage, improve working conditions, but don’t take away the job.

Some of the answers suggested are great:

- Improve manufacturing conditions and processes so they wreak less havoc on people and the environment

- Focus on integrating carbon neutral energy sources into manufacture

- Grow cultivars of cotton that require less water

In fact, different manufacturers and designers have pledged to do one or all of the above. My catalogue from Garnet Hill now offers cashmere made from leftover fibers — a start at least. One of my favorites designers is Eileen Fisher and not just because the clothes are all as comfortable as pajamas. Green Eileen is the platform sponsored by Fisher to provide an upscale venue for her used clothes. The red dot on the label gives it away. I’ve whiled away many pleasurable hours shopping at the Seattle location.

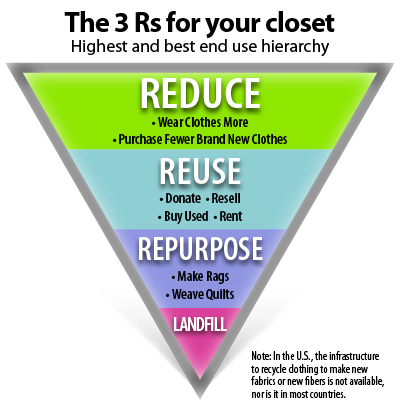

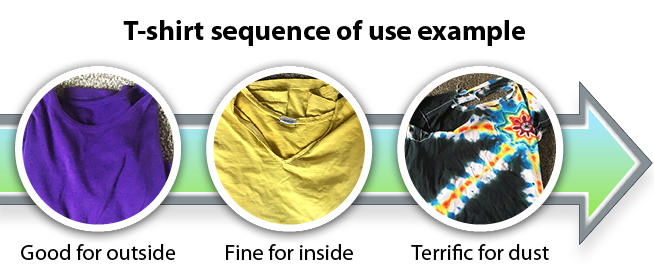

But that is one designer with a very limited number of outlets. On a personal level, the most important thing you can do is to buy less. A big way to accomplish that is to wear what you already own. Emissions associated with clothing and textiles have increased in part because we are buying more and wearing it less. On average, we are wearing those shirts and shorts about 36% less than we did 15 years ago (Ellen MacArthur Foundation). Most of this rarely worn merchandise ends up in landfills — 73% worldwide. Much of the smaller fraction that is recycled is downcycled. That means that the perfectly good pair of pants ends up as mattress stuffing or insulation rather than gracing someone else’s bottom.

But that is one designer with a very limited number of outlets. On a personal level, the most important thing you can do is to buy less. A big way to accomplish that is to wear what you already own. Emissions associated with clothing and textiles have increased in part because we are buying more and wearing it less. On average, we are wearing those shirts and shorts about 36% less than we did 15 years ago (Ellen MacArthur Foundation). Most of this rarely worn merchandise ends up in landfills — 73% worldwide. Much of the smaller fraction that is recycled is downcycled. That means that the perfectly good pair of pants ends up as mattress stuffing or insulation rather than gracing someone else’s bottom.

Fashion Industry And The Circular Economy

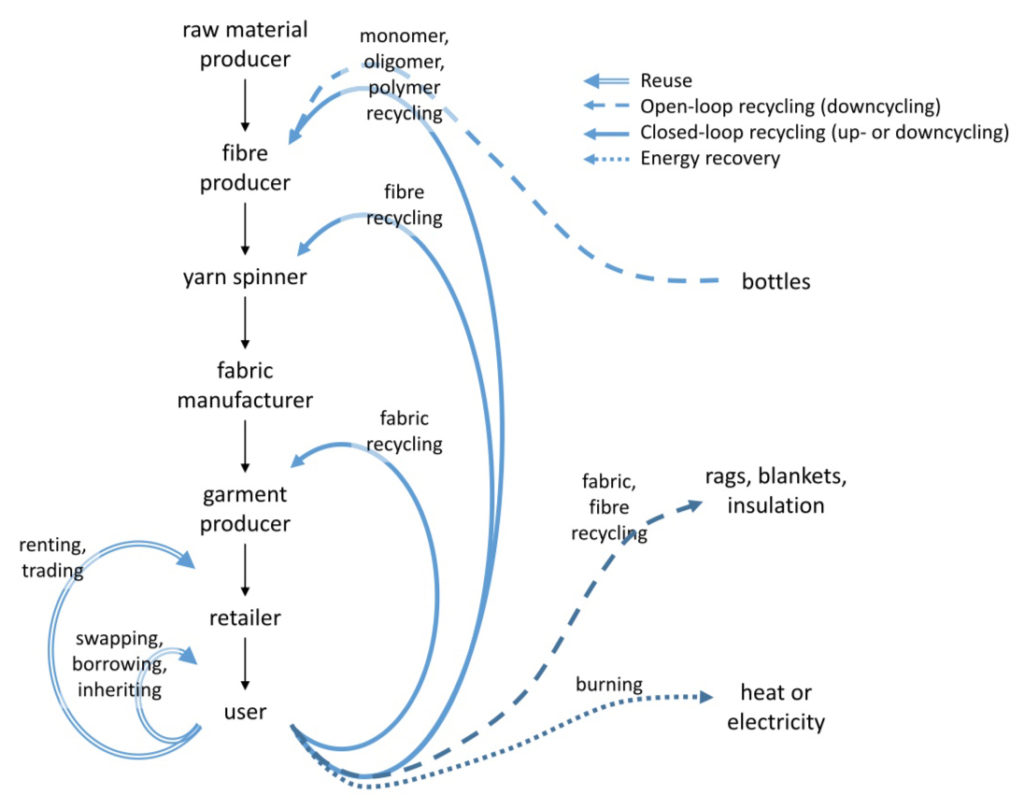

First some basics on trying to get the fashion industry to embrace the circular economy. Recognition of the potential for recycling in the textile industry is just gaining attention. It is happening both to meet consumer demand and to reduce waste. As an emerging practice, there are several levels that are sorting out. Direct textile reuse is what happens when you shop at Goodwill or sell your stuff on line. Textile recycling is a different deal. It refers to reprocessing pre or postconsumer textile waste for use in textile or other products.

Classification of textile reuse and recycling routes. Source: G. Sandin, G.M. Peters / Journal of Cleaner Production 184 (2018) 353-365

This is further divided into cases where the processed fibers are reused directly and those where the fibers are taken apart and reassembled. The latter is more like plastics recycling, which for 63% of our fibers, it actually is. You can find studies in the scientific literature that talk about new technologies to separate and recycle different fabric blends. That is progress. Different countries in Europe have added clothing recycling to the list of items that can be collected. In Germany, for example, 70% of the textiles make their way out of the trash for reuse and recycling. In the U.S., the recycling rate for clothing is well under 5% with about 10.5 million tons of clothes landfilled each year (Newell, 2015).

If you can’t bear the thought of wearing those pants and you know, just really know, that only different ones will do, then reselling, donating and/or buying used are the absolute best way to go. The used clothes business is not something we typically think of when we gear up to fight the battle against climate change. Maybe we should rethink that. Recycling clothing is an exploding business that has a greatly reduced carbon footprint compared with buying new. One study modeled the impact that reuse and recycling would have on carbon emissions associated with the clothing industry and saw a high potential for carbon sequestration.

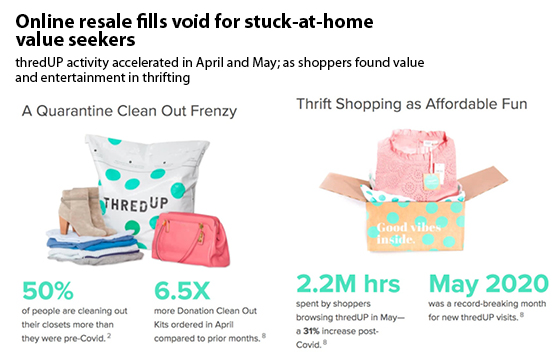

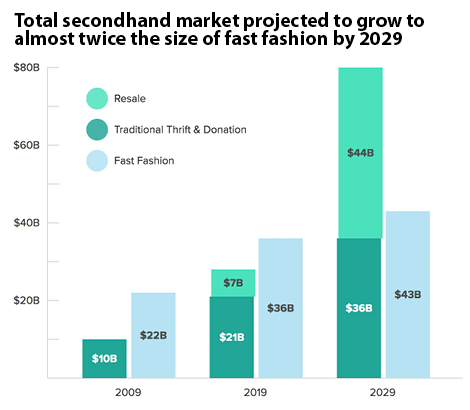

Some of the clothing is a source of income for those doing the recycling. I was thinking that with one of the dresses in one of my bags, but instead decided that it could be the Goodwill find of the week for the right person. The resale market for used clothing — likely now referred to as “preworn” — is expected to grow to $64 billion in 5 years with a current value of $28 billion. It is not limited to local consignment shops. Ebay is one place to look but ThredUp is billing itself as the “world’s largest online thrift shop.” Looking at the ThredUp annual report for this year shows that people are starting to take this notion of “new to me” seriously. Online secondhand is predicted to grow 69% from 2019-2021 while conventional retail is predicted to shrink by 15%. COVID-19 hasn’t put a damper on ThredUp. It appears that resale is the fastest growing sector in fashion. That is a good thing. Rental is another option. Wear that dream dress. Make sure you don’t spill the red wine on it. After that magical evening (we can go out to dinner here in Seattle), return it to the rental shop and let the dream live on.

Some of the clothing is a source of income for those doing the recycling. I was thinking that with one of the dresses in one of my bags, but instead decided that it could be the Goodwill find of the week for the right person. The resale market for used clothing — likely now referred to as “preworn” — is expected to grow to $64 billion in 5 years with a current value of $28 billion. It is not limited to local consignment shops. Ebay is one place to look but ThredUp is billing itself as the “world’s largest online thrift shop.” Looking at the ThredUp annual report for this year shows that people are starting to take this notion of “new to me” seriously. Online secondhand is predicted to grow 69% from 2019-2021 while conventional retail is predicted to shrink by 15%. COVID-19 hasn’t put a damper on ThredUp. It appears that resale is the fastest growing sector in fashion. That is a good thing. Rental is another option. Wear that dream dress. Make sure you don’t spill the red wine on it. After that magical evening (we can go out to dinner here in Seattle), return it to the rental shop and let the dream live on.

Export is yet another option. A portion of those t-shirts from the Goodwill bags go offshore. According to Observatory of Economic Complexity data, globally exports of used clothing were valued at$ 4.38 billion in 2018 with the U.S. as the top exporter ($660 million) and Ukraine as the top importer ($195 million). If you want to see your son’s old high school team shirts you may also consider a trip to Ghana, which imported $172 million of used clothes in 2018.

Outfit Advice

Here is what I would recommend. Don’t deny yourself new clothes. Just make sure that they are not”new” in the traditional sense. For each item you purchase, donate more. A ratio of 1:1 is the bare minimum. See if you can get it up to 1:5. If your closet is at all like mine, you have plenty of options to recycle. Don’t be too hard on yourself. If the dress in your closet gives you pleasure to look at if not wear, it may not be time to let it go. Instead go for the pants that used to fit pre COVID-19. One last tip, don’t buy back the stuff you have just put up for resale or donation. I’ve almost done that myself a few times.

Sally Brown, BioCycle’s Senior Adviser, is a Research Professor in the College of the Environment at the University of Washington.